From The Soho News (July 2, 1980). This was my first encounter with the delightful and inspired couple Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi, subsequently known for their wonderful found-footage films, e.g. From the Pole to the Equator (1987) and Prisoners of War (1995). — J.R.

One interesting thing about aesthetic hybrids — movies with smells, or jazz posing as film criticism — is that nobody knows what to do with them, critics included. Whether these unusual and unlikely yokings represent examples of useful, exploratory or merely wishful thinking is essentially a matter of personal taste. In the two instances under review, a crucial factor in determining one’s taste is packaging, pure and simple — how and where an audience gets placed.

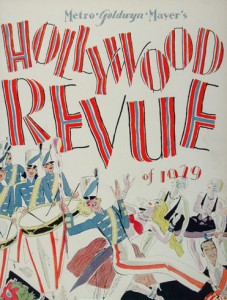

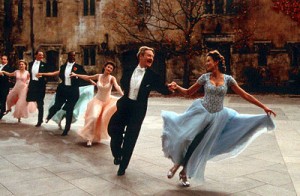

Apart from isolated experiments — including a recent one by Les Blank, reportedly utilizing the odors of red beans and rice — it seems that commercial efforts to link smells with movies have mainly come in two separate, pungent waves. A couple of early talkies, Lilac Time and The Hollywood Revue, played around with the idea in a few theaters; the latter, a plotless musical, climaxed with a snoutful of orange scent to go with “Orange Blossom Time,” performed by Charles King and the Albertina Rasch ballet company. Read more