This was written for a brochure to accompany a retrospective held by Northwestern University’s Block Cinema in January 2008. — J.R.

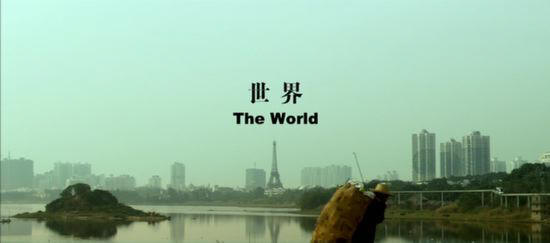

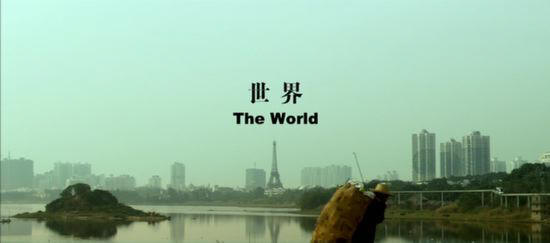

ZHANGKE JIA, POETIC PROPHET

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

What is it about Zhangke Jia that makes him the most exciting

mainland Chinese filmmaker currently working? It might be

oversimplifying matters to describe this writer-director, born in

1970, as a country boy. But the fact that he hails from the small town

of Fenyang in northern China’s Shanxi province clearly plays an

important role in all his features to date. (I’m less certain about what

role it plays in his two recent documentaries, Dong [2006] and

Useless [2007].) Like William Faulkner and Alexander Dovzhenko,

Jia is a hick avant-gardist in the very best sense — someone whose

outsider/minority status enhances both his humanity and his art.

Working in long, choreographed takes, and mixing realistic accounts

of working-class life with diverse forms of cultural shock and fantasy

ranging from animation to SF to rock, he already qualifies as a poetic

prophet of the 21st century, and not only for China.

He attended the Beijing Film Academy, where he

completed his first film, the one-hour Xiao Shan

(Going Home, 1995). I haven’t seen it, but according

to critic Kevin Lee, it’s about a country boy and

unemployed cook in Beijing who wants to go home for

the Chinese New Year and runs into numerous obstacles,

and it utilizes literary intertitles (which also crop up in

his last two features). Read more