From the Autumn 1988 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

“I earn a good living and get a lot of work because of this ridiculous myth about me,” Orson Welles told Kenneth Tynan in the mid-60s. “But the price of it is that when I try to do something serious, something I care about, a great many critics don’t review that particular work, but me in general. They write their standard Welles piece. It’s either the good piece or the bad piece, but they’re both fairly standard.”

Standard Welles pieces were for once not the main bill of fare at a major Welles; retrospective and conference held last May at New York University and the Public Theater. A welcome amount of concrete research into Welles’ work in radio, theatre and film was aired, along with the obligatory theoretical exercises. Sidebars included an extensive exhibition of Welles’s radio shows and materials documenting stage productions, and an effectively staged reading of Moby Dick — Rehearsed, a prime instance of how Wellesian magic could be conjured out of suggestively minimal sounds and images.

In his keynote address, James Naremore offered some fascinating glimpses into the Welles archive in Bloomington, Indiana. The original version of THE STRANGER was half an hour longer, with a flashback structure, a surreal early scene set on a dog-training farm in Argentina and a nightmarish dream sequence.

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 2, 1988). — J.R.

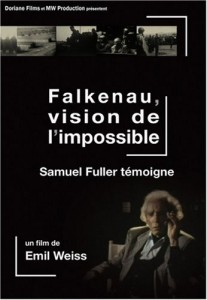

The very first film ever shot by the great American director Samuel Fuller was an amateur effort: as a U.S. army officer he filmed the liberation of a Nazi death camp in Czechoslovakia. French filmmaker Emil Weiss had the excellent idea of reviving this footage, getting Fuller to comment on it, and showing us various relevant locations in Europe today. Fuller’s commanding presence — as a speaker, thinker, and moral conscience — makes this an unforgettable and indelible experience. On the same program with this new short feature is a 1944 Nazi film I haven’t seen but that sounds like the most horrifying film ever made: Kurt Gerron’s The Fuhrer Gives a City to the Jews. A fake documentary produced by the Third Reich as propaganda, the film fabricates an image of Jews living and working happily in a model city. In fact, the film was made by Jews — virtually or literally at gunpoint — and, after it was finished, the director and cast were exterminated in Auschwitz. Fuller’s statement in Falkenau stresses the necessity of remembering the truth of the death camps today, and of denouncing the lies and fabrications of earlier and more recent Nazi apologists, the most chilling evidence of which would seem to be offered in this propaganda feature. Read more

From the March 1978 American Film, when Hollis Alpert was still the editor. If memory serves, this was my first contribution to this magazine. I suspect that the not-quite-accurate title wasn’t mine; like American Film and its parent organization, the American Film Institute, its agenda tends to be needlessly and provincially restricted to American industrial product, unlike those of, say, the British Film Institute or the Cinémathèque Française.

One important informational update: David Meeker’s invaluable reference book has more recently been expanded into an even more invaluable online reference tool that can be accessed here. — J.R.

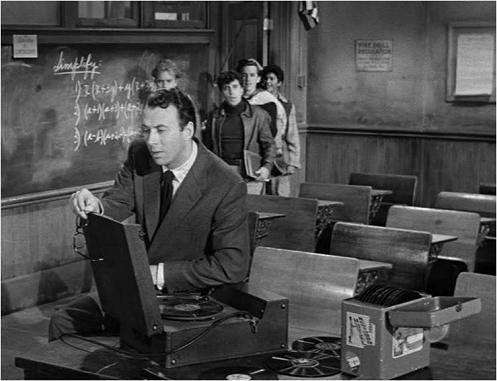

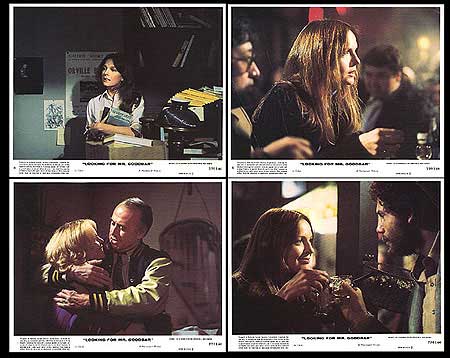

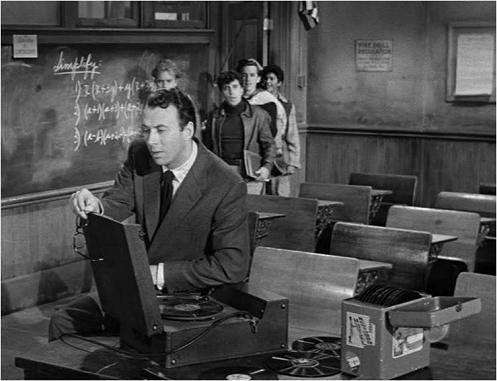

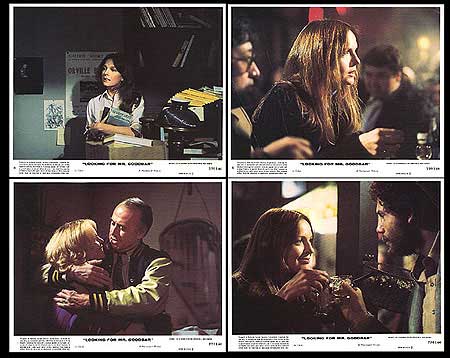

Cuing the audience into the threat of impending violence in Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977), director Richard Brooks has very different aces up his sleeve. In the earlier film, he uses jazz — a blaring, evil-sounding Stan Kenton record. It’s played on a jukebox by Josh (Richard Kiley), a mild-mannered jazz buff and schoolteacher, who is mugged by a gang in an alley while the song is still playing. In the more recent film — where, incidentally, Richard Kiley plays the heroine’s bombastic father — Brooks uses disco singles blasting away in bars, and a strategically placed strobe light. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 12, 2002). — J.R.

Road to Perdition

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Sam Mendes

Written by David Self

With Tom Hanks, Paul Newman, Tyler Hoechlin, Daniel Craig, Jude Law, Stanley Tucci, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Dylan Baker, and Liam Aiken.

It’s based on a graphic novel, which automatically precludes charges of arty pretension — something we all know is found only in literary works and foreign films, not Hollywood movies and comic books. It aims to do for Irish-American crime in the midwest what the Godfather trilogy did for Italian-American crime on the east coast (it uses Rembrandt lighting and fancy period decor, and it aims to be a grand metaphor for the American experience and family ties in general). It offers an array of primed-for-Oscars performances, two of them by former Oscar winners (Tom Hanks and Paul Newman). It recounts a classic tale of revenge, a classic coming-of-age story, and a classic account of bonding between fathers and sons. It dishes up gobs of carefully choreographed, deliberately excessive violence and bloodshed, and then, in the 11th hour, repudiates both — which calls to mind a touchstone like Bonnie and Clyde, as does its populist celebration of Good Country People. Read more

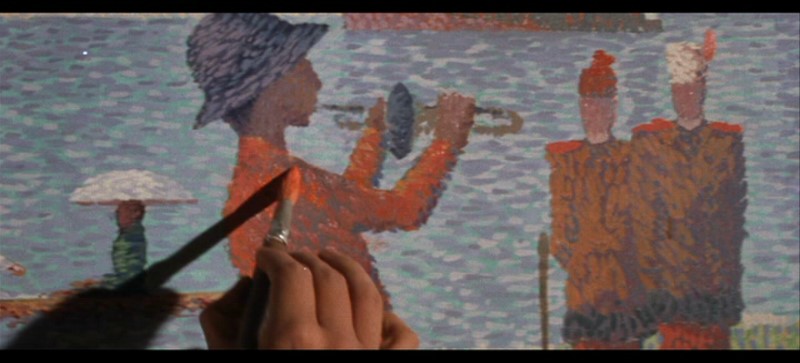

From the Chicago Reader (March 12, 1993). — J.R.

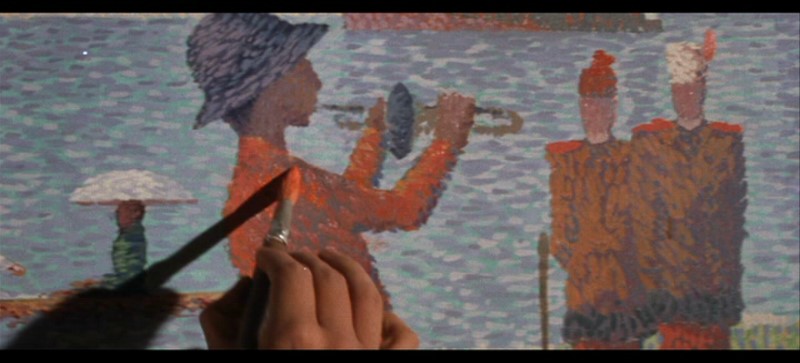

VAN GOGH

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Maurice Pialat

With Jacques Dutronc, Alexandra London, Gerard Sety, Bernard le Coq, Corinne Boudon, and Elsa Zylberstein.

Consider the following two scenarios:

(1) In May 1890, Vincent van Gogh, missing one ear, arrives at Auvers-sur-Oise and meets Dr. Gachet — an avid art collector and fan of the Impressionists contacted by Vincent’s brother Theo — who advises the painter not to worry about his nervous attacks and to concentrate on his work. Taking a room at the Ravoux inn, Vincent follows the good doctor’s advice, but his alienation from others continues to torment him; during Bastille Day, when everyone else is celebrating outside, he sits alone inside, in extreme anguish, at a cafe table. While painting a field he is attacked by crows, and he agitatedly adds a few of these birds to his canvas before pulling out a revolver and shooting himself. He dies shortly afterward, his faithful brother at his bedside.

(2) In May 1890, Vincent van Gogh, both ears intact, arrives at Auvers-sur-Oise, takes a room at the Ravoux inn, and meets Dr. Gachet — an avid art collector and fan of the Impressionists contacted by Vincent’s brother Theo — who advises the painter not to worry about his nervous attacks and to concentrate on his work.

Read more

Recovering this piece, dated March 27, 2000, from an old floppy disk, I no longer have any recollection of who commissioned it or for what publication. [November 2012 postscript: It was the May-June 2000 issue of Film Comment.] — J.R.

Keeping up with Resnais hasn’t been easy. One can find all his recent features on SECAM videos in France, but not the original English versions of I Want to Go Home (1989) or Gershwin (1992). Even Smoking/ No Smoking (1993) — a French adaptation of Alan Ayckbourn’s Intimate Exchanges, a cycle of eight English plays — is available only without subtitles, in a fancy one-box set.

Who would have dreamed that Resnais — supremely international with Hiroshima, mon amour in the 50s, Last Year at Marienbad and La guerre est finie in the 60s, Providence in the 70s — would have wound up a French regionalist in the 80s and 90s, culminating in Same Old Song? This outcome is obviously more a matter of fate than design. It’s not as if Resnais has stood still; the recent features show little of the emotional interiority of his earlier work, veering closer to farce than anything preceding them. Why haven’t most American audiences been able to chart these changes? Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 23, 1993). — J.R.

BOILING POINT

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by James B. Harris

With Wesley Snipes, Dennis Hopper, Lolita Davidovich, Viggo Mortensen, Seymour Cassel, Jonathan Banks, Christine Elise, and Valerie Perrine

BODIES, REST & MOTION

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Michael Steinberg

Written by Roger Hedden

With Phoebe Cates, Bridget Fonda, Tim Roth, Eric Stoltz, Alicia Witt, Sandra Lafferty, and Sidney Dawson.

At least 30 or 40 years separate the sensibilities that underlie Boiling Point and Bodies, Rest & Motion, two current releases I suspect won’t be with us very long. The first, a quirky and at times oddly charming museum piece, is masquerading as a Wesley Snipes action thriller, but advertising — even wall-to-wall — isn’t everything. The writer-director, James B. Harris, who was born in 1928, produced the first three important Stanley Kubrick features — The Killing (1956), Paths of Glory (1957), and Lolita (1962) — and what’s most distinctive about this movie is its bittersweet aroma of 50s nostalgia and over-the-hill desperation, most of it wafting around a pathetically cheerful con artist called Red Diamond (Dennis Hopper) who’s simply trying to stay alive.

There’s desperation aplenty in Bodies, Rest & Motion as well, but not the sort that has the weight of lived experience — or even the relative weightlessness of recollected innocence. Read more

As much as I admire Ernest Lubitsch as a subversive force in 30s Hollywood, especially for The Man I Killed and Trouble in Paradise, I keep coming back to a particular anti-Lubitsch argument made to me by Elaine May, of all people, the one time I was lucky enough to meet her (in Bologna the summer before last). According to her argument, if I remember it correctly, Lubitsch pretended to be more daring, free, and worldly and less middle-class than his films actually were; her main example was Heaven Can Wait, which I suspect irked her in part on feminist grounds. When I asked her if she meant that Lubitsch was roughly akin to someone like H.L. Mencken, she said, “Exactly.”

I remembered this conversation when I recently went through Criterion’s excellent two-disc edition of Lubitsch’s Design for Living (1933), including an interesting interview with Joseph McBride about the script that I saw before reseeing the feature, and William Paul’s superb analysis of both Trouble in Paradise (1932) and Design for Living, which I saw just afterwards. McBride is very good about Lubitsch’s collaboration(s) with Ben Hecht (screenwriter) and Noel Coward (playwright), and Paul is especially acute about the way the usual terms of praise heaped on Lubitsch (such as “sparkling” and “frothy”), which often relate to food and drink metaphors, are actually instruments for undermining the seriousness beneath his playfulness. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 17, 1988). — J.R.

BIG BUSINESS

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Jim Abrahams

Written by Dori Pierson and Marc Rubel

With Bette Midler, Lily Tomlin, Fred Ward, Edward Herrmann, Michele Placido, Daniel Gerroll, and Barry Primus.

RED HEAT

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Walter Hill

Written by Harry Kleiner, Hill, and Troy Kennedy Martin

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, James Belushi, Peter Boyle, Ed O’Ross, Larry Fishburne, and Gina Gershon.

The silly season of summer releases is fully upon us, that time of year when expensive potboilers tend to be the only movies out there demanding our attention. Two interesting-sounding films that might have enlivened this year’s doldrums — Zelly and Me and Stars and Bars, both associated with David Puttnam’s brief stint as head of Columbia — have been unceremoniously dumped by their distributors in suburban Hillside. Paul Mayersberg’s perversely fascinating Nightfall — a head-scratching, low-budget blend of Isaac Asimov, Raul Ruiz, Jasper Johns, and psychedelic Corman movies of the 60s — departed for oblivion (or perhaps for video) before I could review it. What’s left on the table, apart from the delightful Bull Durham, are two mindless romps, each of which makes use of that veritable standby, the double plot. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 19, 1991). — J.R.

BOYZ N THE HOOD* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by John Singleton

With Cuba Gooding Jr., Ice Cube, Morris Chestnut, Larry Fishburne, Angela Bassett, Nia Long, and Tyra Ferrell.

It’s been estimated that at least 19 pictures by black directors will be released in the U.S. this year. That’s less than 5 percent of the total number of features, but still more than the entire output of black-directed movies of the 80s. So far we’ve had New Jack City, The Five Heartbeats, A Rage in Harlem, Jungle Fever, Up Against the Wall, Straight Out of Brooklyn, and now Boyz N the Hood; still to come are Livin’ Large, Talkin’ Dirty After Dark, Hangin’ With the Homeboys, True Identity, House Party 2, Juice, Go Natalie, Daughters of the Dust, Street Wars, Chameleon Street, Perfume, and The Three Muscatels.

Some reviewers have been treating this wave of black pictures as some sort of Golden Age. In terms of the actors, life-styles, slang, and neighborhoods hitting the screen, they may have a point. It’s also true that a sense of urgency in getting a message out gives some of these pictures a vitality and authenticity that they wouldn’t otherwise have; even a movie as technically feeble as Straight Out of Brooklyn has some claim on our attention for this reason. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 5, 2001). My thanks to D.V.@VillalobosJara in Chile for reminding me that I wrote this. — J.R.

I periodically get letters from readers complaining that I write too much about movies they’ve never heard of, some of which come from countries they know little about. A good many examples of these kinds of films are playing over the next couple of weeks at the 37th Chicago International Film Festival.

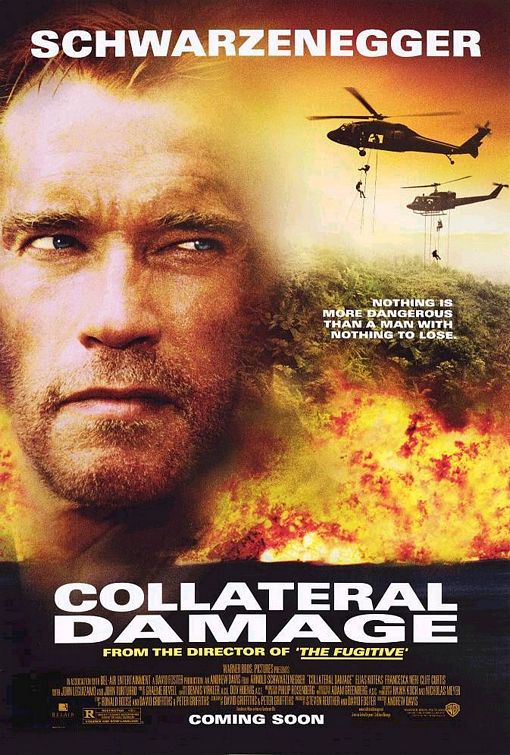

The reason you haven’t heard of most of the 80-odd features on the schedule is that they don’t have multimillion-dollar ad campaigns designed to make them seem as familiar as trees — or Arnold Schwarzenegger. Warners was doing a big campaign for his latest action flick, Collateral Damage, which is about international terrorists who kill his wife and child with a bomb. Before September 11, it was scheduled as the festival’s opening attraction, but Warners belatedly came to its senses and decided not to release it (David Mamet’s Heist was abruptly coughed up as a replacement). There were times in August and early September when posters for Collateral Damage seemed almost as prevalent as American flags have been the past few weeks.

One of the American dream bubbles pricked on September 11 is the idea that we really aren’t part of the world — a delusion that seems inextricably tied to the conviction that we’re safe and invulnerable compared to other countries. Read more

From the December 1, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The first English-language movie (1993) by Bosnian director Emir Kusturica. An orphan (Johnny Depp) working for the New York Department of Fish and Game is asked to serve as best man at the wedding of his uncle (Jerry Lewis), an Arizona Cadillac dealer marrying a Polish woman (Paulina Porizkova) less than half his age. A cousin who comes along (Vincent Gallo) is an aspiring actor whose performances consist of repeating lines and gestures in sync with classic movies. The orphan starts an affair with a widow (Faye Dunaway) nearly twice his age who lives with her neurotic stepdaughter (Lili Taylor). This goofy, disturbing piece of magical realism about dysfunctional families was picked up by Warners, cut by 23 minutes, unsuccessfully test-marketed, and then shelved — until someone got the great idea of releasing the original 142-minute cut. It illustrates the truism that the biggest difference between European and American directors using America as a site for fantasies is that the Europeans are likelier to know what they’re doing. (JR)

Read more

From The Soho News (May 6, 1981). — J.R.

Impostors

Just a Gigolo

Black and White Like Day and Night

Read more

From the January 1973 issue of the short-lived Saturday Review of the Arts. — J.R.

Henri Langlois’s latest creation, the Cinema Museum in Paris, finally opened last summer, a year and a half behind schedule. Only a few of the exhibits were labeled, and five months later the long-awaited catalogue of the exposition has not yet appeared. But even in its present state, the Cinémathèque Française is already the most influential film archive in the world.

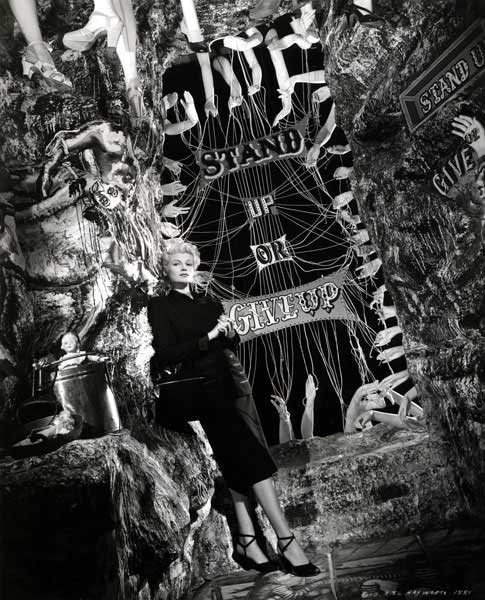

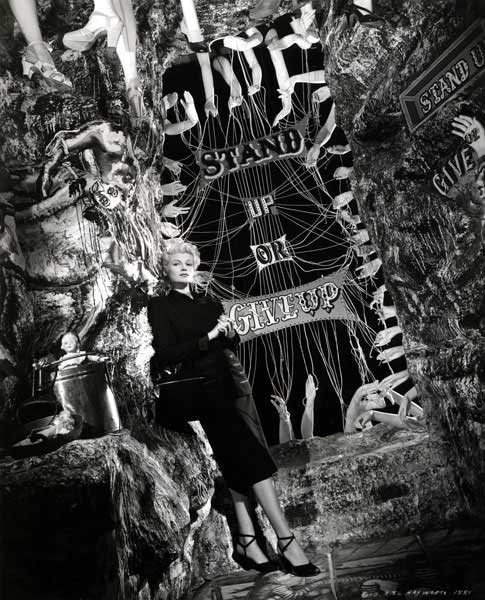

Langlois’s “Seventy-five Years of Word Cinema” occupies sixty rooms in the curving promenade of the Palais de Chaillot, directrly across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower; the present exhibit represents less than one-tenth of the Cinémathèque’s collection of movie memorabilia. From the beginning, the Turkish-born film historian has tried to save everything: to impose selective criteria, he believes,is to anticipate the critical standards of the future. If the result is a cross between a crowded attic and a carnival funhouse, with all its calculated effects, this approach also permitted such young critics as Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, and François Truffaut in the 1950s to take crash courses in every kind of cinema before making their own movies.

The vision of the Cinémathèque’s founder encompasses both Marilyn Monroe and Eisenstein; stray souvenirs and essential artifacts are given equal prominence. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1998). — J.R.

Seeing this singular 1968 American experimental feature by William Greaves a second time (on video; the first time was in 1981, in its original 35-millimeter format) has led me to value it more, though arguably the fact that it loses relatively little impact on video constitutes one of its limitations. Greaves, a pioneering black actor whose career stretches back to postwar films made for black audiences as well as the underrated Hollywood feature Lost Boundaries, went on to direct over 200 documentaries, host and executive produce NET’s Black Journal, and teach acting at the Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute. For this eccentric venture, he got two white actors to play a quarreling couple in Central Park and proceeded to film not only them (in both rehearsal and performance) but also himself and his camera crew and various other people in the vicinity, often juxtaposing two or three camera angles simultaneously in split screen in the final edit. The crew’s own doubts and speculations about the film being made were also recorded later and edited into the mix. The couple’s quarrel is vitriolic and singularly unpleasant, the acting variable, the collective insight into what Greaves is up to mainly uncertain. Read more