The following exchange appeared in Cinema Scope no. 8, September 2001. — J.R.

In the past, when I’ve interviewed filmmakers it’s been at my own initiative — or at least at the initiative of an editor making an assignment. This time, at the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film in April 2001, where I was serving on the jury and introducing Béla Tarr at some of his screenings, someone handed me a tape recorder, and Mark Peranson agreed to transcribe the interview afterwards if I would speak to Béla, who’s been a friend ever since Sátántangó. I hope that the casual grammar on both sides of this conversation doesn’t obscure too much of the meaning. (J.R.)

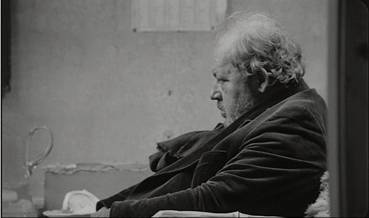

BELA TARR: […] In Sátántangó, we had a set. The doctor’s flat, it was built.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: You know, that’s my favorite scene in the film.

TARR: Yes, but it was built! It is artificial, but you don’t feel it in the movie…

ROSENBAUM: Maybe that’s why I like it so much, because it’s in such a small space.

TARR: No, it wasn’t small.

ROSENBAUM: But it feels small in the film.

TARR: Yeah, sure.

ROSENBAUM: Was the actor playing the doctor a professional actor or a nonprofessional?

TARR: He’s a writer named Peter Berling. He wrote a lot of books on the Middle Ages that are on the bestseller lists in Spain. He played some small characters in a lot of Fassbinder movies and he worked with Werner Herzog. In Fitzcarraldo he was the director of the opera. But you know the other set we built was the opening shot of Damnation, because we had a nice landscape, we had the nice cable cars. But we didn’t have the house — so we built just a window and two walls and some black carpet.

ROSENBAUM: It’s very interesting to learn this. One of the things that’s very interesting to me is how much you’re a master illusionist.

TARR: I don’t know. Because this is real practical work, and just listening always which is real, and how we can do it, I never think about…

ROSENBAUM: I know, but it’s still significant to me that many people who see Sátántangó get very upset about the cat, because they think this was really done to the cat. And it wasn’t. The point is that they are seduced into the narrative in a way that it feels very real.

TARR: But you know, this is my job. I just do that. 1 just wanted to make some tension. You know, the cat is still alive….

ROSENBAUM: And it’s your cat.

TARR: No, it’s not my cat. But I have a cat at home and I have two dogs, it is impossible for me to kill or destroy any animal.

ROSENBAUM: I thought you said it was one that actually you adopted after the film…

TARR: No, no. It was one cat of a friend of mine. She just slept a little. She just got an injection, and she slept. There was an animal doctor and it was very safe. When the girl is jumping with the cat, they also just played. And all of the sound that was used was artificial, it was from the sound archive.

ROSENBAUM: One thing that interested me, when I saw Sátántangó again, it seemed to me that the doctor was the hero, which I hadn’t thought of before. And you said that the only other one that’s a good character is the girl, because she’s innocent.

TARR: Yeah, but you know, who is to say about good or bad?

ROSENBAUM: Relative to the other characters, that’s what I mean.

TARR: I think they have a different position. The doctor, he’s just observing. But you know he isn’t the real hero, because he missed what has happened, he has definitely missed everything. And when he came back, the whole thing doesn’t exist. But he believes. This is also very strange because he’s also in the trap. Everybody’s in the trap. That’s the problem. Everybody left, and he just started writing again, and he believes everything is the same, but everything has changed. That’s why I think he is not the real hero.

ROSENBAUM: But he hasn’t been fooled in the same way that the other characters have been.

TARR: Yeah, sure, because he has a different cultural background. You know, maybe this is our personal opinion, maybe this is a kind of mentality how we can live, just to be.

ROSENBAUM: To me what’s very interesting is that the two most powerful sequences in the film are the sequence with the doctor and the sequence with the little girl. And they’re the two sequences that are about people who are alone. The rest of the film is about people who are together. And it becomes a different universe in a way, for the people who are all together. The kinds of deceptions are different, and the kinds of ambition are different. To me the film is a dialectic between those two things. And the spectator spends more time with the other people overall, so you have to become people who are in a group and people who are alone in the course of watching the film. And that’s what I think is so necessary about the long takes. Because when you have long takes, you share so much with these people that you have to become morally identified with them in some way. It’s not simply observing them.

TARR: Sure, because I must tell you some practical things. What you mention to me, it’s the kind of the tension. You know, you have actors, and I always apply their personalities. if I have a long take, six minutes, I don’t say too much to the actors. I just say what is the situation. And I say, okay, shoot. They just develop something from their personalities, some deep things, because they have no instructions — they are just in the situation. You can see in their eyes how they are. And that’s the most important thing. You know, because they are being, they are really reacting, they have no help, they must listen to each other, they must do, they must react to each other! If they don’t do it, I stop the take and go back to one, and we start again.

ROSENBAUM: Aren’t they reacting to you too, because you’re saying you have to move here and do this?

TARR: Yeah, yeah, sure, but the most important thing is their presence, how they are present in the situation. That’s the difference. I’ve seen how some other filmmakers work, they give a lot of instructions to the actors, and I never understand why. Because they don’t trust them. I trust my people! Because if I choose them, and I say, “Okay, you will be the main character,” and then don’t say anything, just come and do it. Then afterwards, you have a special tension, because they must develop something from inside.

ROSENBAUM: I always like to think that you could divide all filmmakers into filmmakers for whom a shot is a declarative sentence, and filmmakers for whom a shot is a question. And in a way what you’re saying is that for you a shot is a question. And what the people do is the answer.

TARR: And they have six minutes. They cannot escape from the situation. You know, several times they’ve finished the scene and I just leave it, I didn’t stop the camera, and they are in the situation. And several times, I just said, okay, the camera is rolling, let’s just start again, from the beginning.

ROSENBAUM: Is this the same way you worked on both Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies?

TARR: It was the same from the first movie. How I work with the actors was similar. In Sátántangó, we used only three times a perfect text, including Irimias’ funeral speech, because it was very well written, and the second long Irimias speech about eternity. But the other text was very flexible, and I just left it to the people. Okay, just say what you feel, because it’s much better than what we can write.

ROSENBAUM: But yet at the same time there are sequences, for example, the sequence with the doctor sitting at his desk, where you feel that every gesture is part of a composition, you don’t feel that it’s improvising.

TARR: No, no, no. Because his personality, Peter Berling, you know…when we found a good chair for him. We had five chairs. We just showed every one to him, and I asked him to please sit and try which is best for him. He said, “The third, that’s the one I like.” I said, “Okay, that’s really your place. You just sit there.” He couldn’t move. It was really difficult for him. You know, his personality, he likes putting everything in order, because he’s German. The whole character was ready when he was sitting in the chair and just watching how he makes order. I asked him, please arrange everything how you normally write. And afterwards, it was ready, the whole character and everything, it was ready…

ROSENBAUM: So it wasn’t just your composition. It’s also his…

TARR: Yes, of course, because if he is not comfortable, he can’t be. I’m not an aggressive director, who is forcing something, which is not interesting. You cannot force people, under the pressure, in ten minutes…

ROSENBAUM: What about the way that you directed the soundtrack? Because what’s so important in that sequence is his breathing. When you did the sound separately, was it his voice or did you use another voice?

TARR: No, it was dubbed. You know it’s very strange because the guy who dubbed the doctor plays the circus director in Werckmeister.

ROSENBAUM: To me part of the comedy that I liked so much in the sequence was how so much work was required just to sit there and get drunk — the labor of every movement. And in a way the sound of the breathing is what articulates that. Like he’s climbing a mountain.

TARR: I can’t say anything about that, you know, it’s a very practical thing.

ROSENBAUM: No, I understand.

TARR: It’s something, it was very difficult to do, because several times my cameraman didn’t want to do something because he always says it’s impossible to turn the camera here (gesturing)…

ROSENBAUM: When he’s writing…

TARR: Yes, the camera is here, and he’s writing and afterwards it goes there, and he’s watching how he’s putting something, and my cameraman says always that it’s impossible. And I have a very good dolly guy, and he has a lot of ideas, how we can do what I want. That’s the reason when the cameraman changes, the dolly guy remains the same!

ROSENBAUM: Was it very hard to do the part of the shot where Berling falls down?

TARR: We shot it only three times, and we used the second one. If you have a good take, afterwards I make only one more, always, because you are never safe. The lab could make some mistakes.…I was very surprised, because he’s 140 kilograms, but when he falls down, Jesus Christ! The first time I just sat behind the camera and thought, Jesus Christ, he’s never going to get up. When he’s sitting, he’s okay, but when he’s walking he’s very fast. I had to force him, don’t run, Peter, don’t run!

ROSENBAUM: It’s also interesting how much of Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies is devoted to people walking. In a way it’s meditative, but it also becomes almost like a metaphor for narrative itself…

TARR: Don’t tell me anything about metaphors!

ROSENBAUM: You hate metaphors, you hate allegories, you hate symbols…But I think the problem that people have, more with allegories than the other two, is because it’s impossible for most people outside of Eastern Europe to look at anything inside of Eastern Europe and not see allegories…You have to understand that when I say metaphor for narrative, I’m not saying this is your idea, I’m saying this is my idea. And the reason why, which I think is important, is it becomes the issue again of becoming implicated in what the characters are doing. In Sátántangó, when you follow someone walking, it’s almost like a rest between the more dramatic things.

TARR: Maybe. Okay, I try and explain it to you. You know, if you are in the Hungarian plain in the early morning, before the shooting, and you are just sitting there, just watching. And you just watch the perspective. And you don’t know what you see. Is this one endless hopelessness? You really don’t know. Is this eternity or just relativity? That is what I really don’t know. When they are walking, you know, I have the same feeling, always, what is this, is this real distance or we are just…? You know, like a treadmill they are just walking, walking, just endless walking. Do you have perspective, or hope, or just nothing, or always staying there, in one point? That was the case in Sátántangó….[In Werckmeister Harmonies], it’s completely different.

ROSENBAUM: No it is, I see. But I think the only way for me that it’s similar, which is important, is that I experience it in some way in musical terms. In Sátántangó — do you know the term pedal point? It’s when you hold a chord for a very long time. And when you hold a chord for a long time it becomes meditative, because it gives you time to think, and almost makes a demand on your imagination. And that’s really interesting, because it comes at certain points in the narrative in Sátántangó when it’s very important to have time to think. To me, that’s what’s so beautiful about the portions from the novel read offscreen that come at the very end of the sequences. And I think that is involved also with a kind of identification that may not even be conscious, but still plays a part into how one gets involved with these people.

TARR: I understand. When we started to think about Sátántangó, in the beginning, we wrote a script for the producers and the money, and it was very linear. Without chapters, it was just a story. It looks like a movie story. It took nine years to get the money. When we started to think about it, I sat together with Agnes [Hranitzky, Tarr’s editor and partner] and László [Krasznahorkai], and we thought, now, okay, we forget the script, and went back to the original structure. Because it was a minimum six hour long movie, that was sure at the beginning. And we thought we couldn’t make a linear, six hour-long story without any break, and we decided immediately, let’s go back to this chapter structure. And we also thought, what if nobody wanted to distribute it, then we would have 12 short movies. Twelve chapters, this is very simple, and at the end of every chapter, we will use some sentence from the novel.

ROSENBAUM: What I find very beautiful about it is it kind of extends the story in another direction, in the imagination. To me, one of my favorites is the one with the people in the office, when you hear what happens when they go home at night. It makes the relation between cinema and literature so close, when they’re usually at opposite ends. You somehow bring them together.

TARR: Yeah, sure, because Krasznahorkai’s language is absolutely impossible to adapt for the movie…

ROSENBAUM: Because it’s stream of consciousness, partly …

TARR: Yes, but our point of view is similar, how he watches the world and how I watch the world. That’s the reason why we are sitting together, we can talk about life. When we are writing the script, we are talking about concrete things…

ROSENBAUM: Is he around during the shooting at all?

TARR: No, no. He is a typical writer from the 19th century. He was on the set two or three times in the shooting, and nobody listens to the writer, everyone has practical work. He just wanted to sit and say this is a very primitive job, a shit job, because you never talk about the art, you never say nothing to the actors, you never say any intelligent things, only practical things. And he always escaped from the shooting.

ROSENBAUM: By the way, apart from The Melancholy of Resistance [the novel Werckmesiter Harmonies is based on] in English, have there been other translations, and in what languages?

TARR: Sátántangó was translated into German and French, published by Gallimard. And I hope that there will be a translation in English finally.

ROSENBAUM: You know that there’s part of one chapter in English, that’s all.

TARR: Yes, but someone told me it’s a shit translation. But he’s a really good writer, and I hope somebody will translate it…His style is really middle European. It looks like Thomas Bernhard, Kafka and the others…

ROSENBAUM: I believe you, but I can’t still see [Sátántangó] without thinking of Faulkner. They’re cultural equivalents in a strange sort of way. Because Faulkner is rural, stream of consciousness, the same day from different points of view — more than one writer does these things.

TARR: You don’t understand how shit the translations of Faulkner are in Hungarian. That’s always the problem — I’m really, really sad that I can’t read them…

ROSENBAUM: I can’t read Kafka properly, either…

TARR: Or like Joyce, Finnegans Wake, what can you do with it in another language? You can’t do nothing! You can’t understand. That’s the reason why I think that literature is always limited. If somebody lucky is writing in English, there’s a bigger audience. But you know a Hungarian writer, there’s only 10 million or 15 million people reading it. [Cue to end] I really enjoyed this, I’m lucky, you were an excellent interviewer.

ROSENBAUM: This is very interesting, I learned a lot.

TARR: We were just talking.

— Cinema Scope no. 8, September 2001.