From The Soho News (February 11, 1981), slightly revised. This is the first of my ten Soho News columns with that title, and the only one without a subtitle. — J.R.

Jan. 23; Arriving at the Collective [for Living Cinema] too late to absorb either of Gail Camhi’s 1980 quickies, I’m plunged almost at once into her lovely 22-minute Bellevue Film (1977-78), also silent, which is just what its title and program note say it is: “A look at physical therapy, having profited from it.”

What’s lovely about that?, one might ask, although no one at this crowded screeni9ng seems to be asking it. Russian Formalism associates art with defamiliarization, “making strange”. Gail Camhi seems to be doing just the reverse – showing how ordinary, say, amputees and their stumps and artificial limbs are, making them familiar and banal presences rather than fearfully charged objects. Yet by removing (to some extent) myth and other forms of fantasy from a hospital ward, she may actually be inviting the aesthetic imagination to relocate itself elsewhere in the film – not merely banishing this imagination to purgatory, as some arguments would have it.

The 13-minute An Evening at Home (1979) — a black and white sound “musical” featuring Camhi’s father in three charmingly modest vaudeville turns, performed in his own living room -– calls to mind an old-fashioned dream I once had in Paris: to film every one of my friends dancing with wild abandon somewhere near the Seine, and then to spend the next year syncing this footage precisely to an Ahmad Jamal cut. Using Pere Camhi and an Al Jolson anthem and campy foxtrot (among other things), this laid-back effort succeeds in capturing the euphoria of that scheme without the innocent pedantry that went with it — once again, by following the “realist” tactic of letting personality triumph over form. But this simple approach finally draws a pristine blank in the 1976 Coffee Break, 15 interminable minutes long – a film which suggests a reduced, self-conscious version of 9 to 5 minus stars, script, sound and humor, reduced to a single cramped set.

Jan. 24 (again at the Collective): Every once in a while, programmer Renee Shafransky will book a film because she’s intrigued by the catalogue description. This is one of those hit-or-miss nights, and lo and behold! a mangy 1939 program filler called Café Hostess, directed (if one can call it that) by one Sidney Salkow, turns out to be just as dreadful as it sounds, despite a proto-feminist gloss in the printed title at the beginning. So doggedly formulaic and mulish about its reluctance to try for charm that I find it induces a heavy dose of plot amnesia while it’s still in progress, Café Hostess still justifies its own existence by offering Shafransky the occasion to show a recent film, Lauren Abrams’ Hustle of the Heart, as an unannounced addition to the program.

The latter is a lyrical, polished sound and color “home movie” that cheerfully does about the same sort of thing for a sleazy strip joint (and its employees and patrons) that Camhi does for (and with) the hospital ward in Bellevue Film. That is, it allows certain individuals to emerge and even prevail over concepts — in this case, sexist and feminist commonplaces. You might subtitle it, “a look at pornography, having profited from it,” although in fairness to Abrams, a nice daydream sequence introduces a certain ambivalence to her documentary.

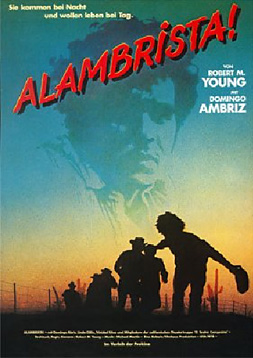

Jan. 28: At a midtown press show, I take a belated second look at Robert M. Young’s likable and stirring first feature, Alambrista! (The Illegal) – first seen at the Toronto Film Festival back in ’79, when it was already two or three years old, and finally turning up here at the Public Theater, still fresh as ever. (Playdates are Feb. 1015, 17-22 and 24-26.)

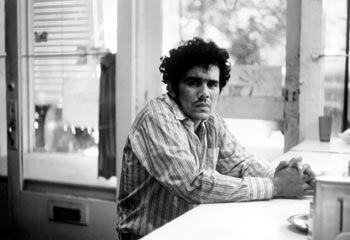

A protest film about a young Mexican alien, Roberto (Domingo Ambriz), who keeps sneaking across the U.S. border to work, it evokes some of the anger, dusty pathos and weary poetry of a Nelson Algren Depression novel — a circular sort of lament about futile existence on a subproletarian level. Conceived, directed, written and shot by the man who has since directed Short Eyes, Rich Kinds and One Trick Pony (none of which I’ve seen), it neither looks nor plays like a first film. But this shouldn’t be surprising, as Young is a filmmaking veteran whose professional experience includes several underwater documentaries of the 50s, documentary ‘White Paper” specials in the 60s, and an Emmy-winning film about Eskimos in the 70s.

The movie usually works best when it becomes least “descriptive” in a prosaic documentary sense. There are some dazzling hand-held subjective shots of Roberto running and hiding from border cops in a field (before discovering that he won’t be paid for his fruitpicking), and a very funny episode when a pal named Joe (Trinidad Silva) teaches him how to smile like the gringos and order “ham, eggs and coffee” in cafes to cover his lack of English.

I once lived across an alley in La Jolla from a halfway house where runaway Mexicans were periodically holed up, and I probably knew even less about them than they knew about me. Apart from Martha Rosler’s story “Tijuana Maid” (reprinted in her Service: A Trilogy on Colonization, which is available from Printed Matter), Alambrista! is the only work I know of that deals with these people at any length, and even if a few points come across heavy-handedly (such as a Mexican woman climactically giving birth at a U.S. border station, occasioning her line, “My son won’t need papers!”), the information conveyed is never less than absorbing.

Better yet, the story conveys a rather uncanny sense of what gringos (like Ned Beatty, in a secondary part) look like to folks from across the border — a fascinating subject all by itself. There’s an exhilarating sequence when Roberto and Joe hop a railway car carrying automobiles, one of which they joyfully climb inside, and an amusing bit of bordertown sociology and suspense when Roberto has to pretend to understand a local yokel at a cafe counter rattling on in English while a cop sits down beside them.

Feb. 6: QUESTION: What do Regan’s inauguration and the recent presentations of Gance’s Napoleon at Radio City Music Hall and Gary Indiana’s video play A Coupla White Faggots Sitting Around Talking — shot, directed and edited by Michel Auder, and shown twice tonight on five monitors at the Kitchen — have in common? ANSWER: All three are offered and appreciated primarily as events, not as works or deeds. The fact that, by and large, the audiences for all three are singularly uninterested in (a) politics, (b) cinema or (c) video is not so much a distraction to these occurrences as the prerequisite which makes them possible and successful, socially as well as existentially.

I have to admit that I find (c) more entertaining in spots than (a) or (b), if only because the social context defining it is somewhat looser, giving me a wider space in which to wallow. But speaking as someone who enjoyed Indiana’s theatrical entertainments more when they were being staged here in various lofts, gardens and the Mudd Club, I must admit that I miss the sharper, nastier political edge of these earlier forays. (It’s true that Indiana directed these, which might have given their themes a harder focus.)

Insofar as A Coupla White Faggots has a plot, it doesn’t stray much farther than its initial Harold Robbins premises. Dom (Indiana) — the gay son of a famous California politician, offered $5000 and some of his sister’s clothes if he’ll stay away from her wedding — befriends his neighbors, a dominatrix (Cookie Mueller [see below]) and a blocked, frustrated gay author (“Handheld Coffins“) and TV personality named Rippley (Taylor Mead). At the Colonnades, Dom meets Buddy (Jackie Curtis), who boasts “a prostate as big as the Ritz”; the dominatrix makes a house call; Rippley interviews a champion swimmer (Florence Lambert) by the East River, and complains to Dom, “If you have to go out looking for sex, that uses up all the energy you need for watching television”; a little girl (Alexandra Auder) turns up, spouts obscenities and sings about blackheads; and so on. (Meanwhile, Pere Auder oddly intercuts diverse kinds of black and white archive footage.)

Clearly this is a weak season for concepts. Despite some references to Wilde and Syberberg, and an Angel of Death in a toga (Geoffrey Carey) who chants Latin from a roof, the pleasures in this superstar sitcom are mainly local and actorly. In contrast to an Indiana opus like Alligator Girls Go To College, the laughs usually come from the deliveries: Curtis and Indiana noisily simulating offscreen sex; Mead pumping up a Mae West comeback to Curtis’s “I move furniture” (“I got some furniture that hasn’t been moved in years”) with all the relish of a seasoned pro.