From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1976, Vol. 43, No. 504. — J.R.

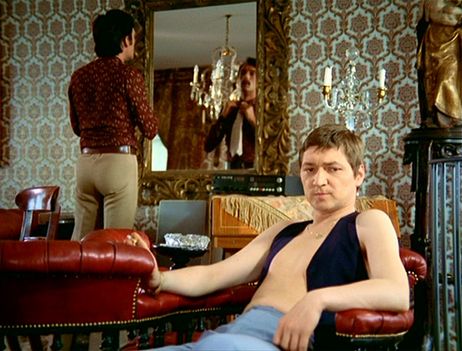

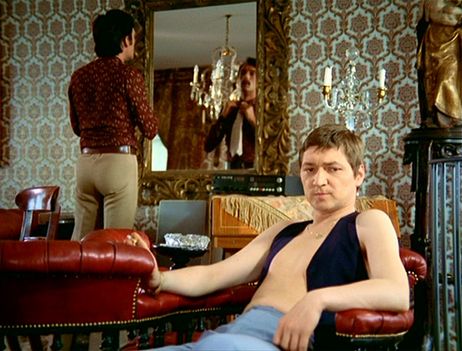

Faustrecht der Freiheit (Fox)

West Germany, 1975

Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Ce r t–X. dist–Cinegate. p.c–Tango-Film. p–Rainer Werner Fassbinder. p. manager–Christian Hohoff. asst. d–Irm Hermann. sc—Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Christian Hohoff. ph–Mictrael Ballhaus. col–Eastman Colour. ed–Thea Eymèsz. a.d–Kurt Raab. m–Peer Raben. songs–“One Night” by Pearl King, Dave Bartholomew, performed by Elvis Presley; “Bird on the Wire” by and performed by Leonard Cohen. l.p–Rainer Werner Fassbinder (“Fox” Franz Biberkopf), Peter Chatel (Eugen Theiss), Karl- Heinz Böhm (Max), Harry Bär (Philip), Adrian Hoven (Eugen’s Father), Ulla Jacobsen (Eugen’s Mother), Christiane Maybach (Hedwig), Peter Kern (Florist “Fatty” Schmidt), Hans Zandler (Man in Bar), Kurt Raab (Barman Springer),Irm Hermann (Mlle. Chérie de Paris), Barbara Valentin (Max’s Wife), Walter Sedlmayr (Car Dealer), Ingrid Caven (Singer in Bar), (El Hedi Ben Salem (Moroccan), Brigitte Mira (Shopkeeper),Bruce Low (Soldier), Ursula Strätz, Elma Karlowa, Evelyn Künneke, Marquart Bohm, Liselone Eder, Klaus Löwitsch.

11,077 ft. 123 mins. Subtitles.

“Fox” Franz Biberkopf, a carnival sideshow performer, loses his job and his lover Klaus (who runs the show) when the latter is arrested. Read more

There’s a particular Parisian tradition that seems peculiar to French aesthetics involving a certain license to behave like a depraved lunatic and receive approval, endorsement, and other cultural rewards in return for this boorishness.(Many years back I tried writing about this subject, in a long review of My Life and Times with Antonin Artaud.) I suppose one very bourgeois way of describing this tendency would be to call it the aesthetics of self-indulgence combined with a gift for self-promotion, and though I don’t know French literature well enough to determine what poets might have established this trend (apart from such relatively modern figures as Baudelaire and Rimbaud), there’s no question that Jean Cocteau set down many of the terms and conditions of this tradition in cinema, along with the visiting Spaniards Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali — including, perhaps, a special talent for hustling up various forms of patronage.

Even though not all artists with these characteristics are French, much less Parisian, it could perhaps be argued that those who are commonly celebrated for these traits are typically appreciated either by French critics (Nicole Brenez writing about Abel Ferrara) or Francophile critics (such as Adrian Martin writing about Philippe Grandrieux, among many others). Read more

From Sight and Sound (Spring 1983). -– J.R.

Wayne Wang: Chinese structures and American economies

Opening with a rousing Cantonese version of ‘Rock Around the Clock’ which is all about inflation — the rising cost of tea and rice — Wayne Wang’s remarkable, offbeat Chan is Missing neatly combines its concern about what it means to be Chinese-American with the current economic crisis. Praised in these pages by Richard Combs after its appearance at the 1982 London festival as a film that ‘answers nothing, but in a way satisfies one’s curiosity,’ this black and white mystery, about two Oriental cab drivers searching for their missing partner through San Francisco’s Chinatown, has done surprisingly well since its U.S. release last fall, especially for an independent feature costing under $20,000. A strong review from the New York Times‘ Vincent Canby, coupled with careful handling by New Yorker Films, helped to turn the film into something of a commercial sleeper. ‘After the first quarterly report, we were already in the black,’ Wang cheerfully told me on the phone from San Francisco early this year, adding that the cast and crew members, who had originally been partially paid off in points, were already just starting to get proceeds for work done in 1980. Read more

Joseph McBride, a friend, asked me to contribute a list of some sort to The Book of Movie Lists (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1999), which he put together, and here’s what we came up with. -– J.R.

The 10 Best Jazz Films

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

What follows is a personal list of neither the best films on jazz (e.g., Jazz on A Summer’s Day) nor the best examples of jazz on film (such as the Fats Waller soundies or the 1981 Johnny Griffin at the Village Vanguard), but something more special and rarified: films in which the aesthetics of jazz and the aesthetics of film find some happy and mutually supportive meeting ground.

1.Black & Tan (DUDLEY MURPHY, 1929). Remarkable not only as an experimental narrative by the (often uncredited) main author of Ballet mécanique and as a radical political statement about to whom jazz belongs, but also as a ravishing, poetic marriage between the music of Duke Ellington and the poetics of death and orgasm. Only twenty-one minutes long, but the aesthetics of jazz and film start here.

2.When it Rains (CHARLES BURNETT, 1995). A twelve-minute miracle, and, alas, the only film on this list by a black filmmaker, this is a jazz parable about the discovery of common ‘6os roots via a John Handy album in contemporary L.A., Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 20, 1992). — J.R.

MR. COCONUT

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Clifton Ko

Written by Ko, Michael Hui, and Raymond Wong

With Hui, Wong, Olivia Cheng, Ricky Hui, Maria Cordero, and Joi Wong.

KING OF CHESS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Yim Ho and Tsui Hark

Written by Yim and Tony Leung

With Leung, John Sham, Yong Lin, Yia Ho, King Shin Chien, and Chan Koon Cheung.

![Mr. Coconut[DVDRip] 450c5e100a576972b5dc85c0a24988d7 Mr. Coconut[DVDRip]](http://img.emuleday.com/data/img/45/450c5e100a576972b5dc85c0a24988d7.jpg)

Past, present or future . . . China will always belong to the Chinese people. — opening title in King of Chess

In this country there is probably no important national cinema more neglected than the Chinese — actually a transnational entity, as I’m defining it here, including movies from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. And probably no programmer in this country is more dedicated to making Chinese cinema known than Barbara Scharres, director of the Film Center.

I have to admit to a certain resistance to Chinese cinema in the past, and to Hong Kong movies in particular. It’s a bias shared by many of my colleagues, for reasons that are in part self-serving: if we were to suddenly acknowledge the importance of Hong Kong movies, we’d be forced to acknowledge many years of negligence on our part, and obliged to admit an embarrassing lack of knowledge and sophistication on the subject. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 23, 1993). — J.R.

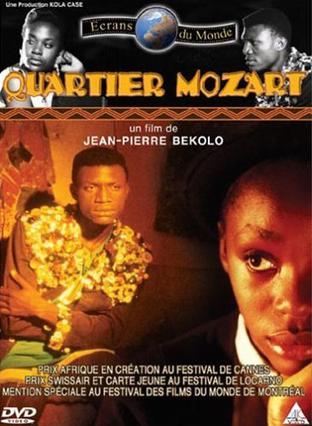

MOZART QUARTER

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Jean-Pierre Bekolo

With Serge Amougou, Sandrine Ola’a, Jimmy Biyong, Essindi Mindja, Atebass, and Timoleon Boyongueno.

I cannot tell a lie. I couldn’t follow all the plot details of Mozart Quarter — Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s delightful comic fantasy about contemporary sex relations in a working-class neighborhood in Yaounde, Cameroon — even after I saw it a third time. Some of my confusion was probably due to the subtitler’s effort to render part of the French African dialogue in American inner-city slang — an understandable goal, but one that sometimes sacrifices lucidity for superficial familiarity and occasionally produces outright gibberish. Another problem is that certain Western cultural artifacts have meanings specific to the oral story-telling culture out of which Mozart Quarter arises.

Yet this wasn’t an obstacle to my enjoyment of the film, which is playing five times this week at the Film Center; on the contrary, it operated more as an incentive. If the common liberal error in understanding non-Western societies is to assume they’re exactly like us and the common conservative error is to assume they’re nothing like us, any movie that confounds both sides is bound to have a few things to teach us. Read more

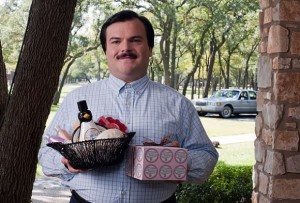

My 27th column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, formerly known as Cahiers du Cinéma España, which appeared, I believe, in their July-August 2012 issue. — J.R.

I have a habit as a critic that I suspect irritates some of my readers. When I find that my opinion about a new film differs substantially from that of the mainstream, I sometimes theorize that the reasons for this must be ideological. In this manner, I speculated that the immoderate fascination of other Americans with the mad serial killers of The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and No Country for Old Men (2007), which somehow seemed motivated by a twisted identification with them -– and especially with the capacity and eagerness of these psychotics to kill innocent people without any compunctions — were related to the fact that these films came out during the first and second Gulf wars, when Americans were killing innocent people with no compunctions at all, and sometimes even exhibiting comparable displays of glee about this mindless activity.

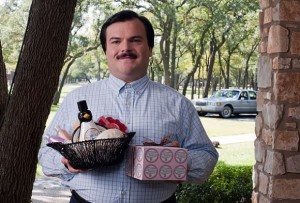

More recently, I’ve been puzzling over the fact that Richard Linklater’s latest feature, Bernie, a masterpiece that has been clearly delighting many of the audiences that come to see it, was only released after many delays, wasn’t sent to Cannes, and has been doing poorly at the box office — a fate similar to that of Linklater’s previous feature, Me and Orson Welles (2011), another treasured project which took him many years to finance, and one also dominated by a remarkable central performance (Christian McKay as Orson Welles, Jack Black as Bernie Tiede). Read more

From the Santa Barbara News & Review, October 24, 1985.–- J.R.

The Man Who Envied Women, introduced by filmmaker Yvonne Rainer, will be shown at 8 pm Monday, Oct. 28, Isla Vista Theatre II, Embarcadero Del Norte. Free admission.

It doesn’t really do justice to Yvonne Rainer’s exhilarating The Man Who Envied Women to call it avant- garde — or even the best feature to date by New York’s most celebrated avant-garde filmmaker. To do that is to consign it to a gilt-eged ghetto presided over by experts. The fact that Santa Barbara is fortunate enough to be getting this movie in advance of both New York and Los Angeles — and with Rainer herself in attendance -– shouldn’tmean that we need any big-city explicators to crack the surface of her intellectual vaudeville. Admittedly, there’s enough theoretical discourse on display to choke a horse, and two actors rather than one (a favorite Rainer ploy) portraying the title character — a complacent, womanizing academic named Jack Deller whose second wife, a nameless voice, leaves him in the opening moments of the film. But the delightful thing about Rainer’s word and image salad is that its deliberate overload virtually guarantees that if we miss a particular gag or argument, we’ll find its near-equivalent lying in wait for us a few minutes later. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Spring 1987). –- J.R.

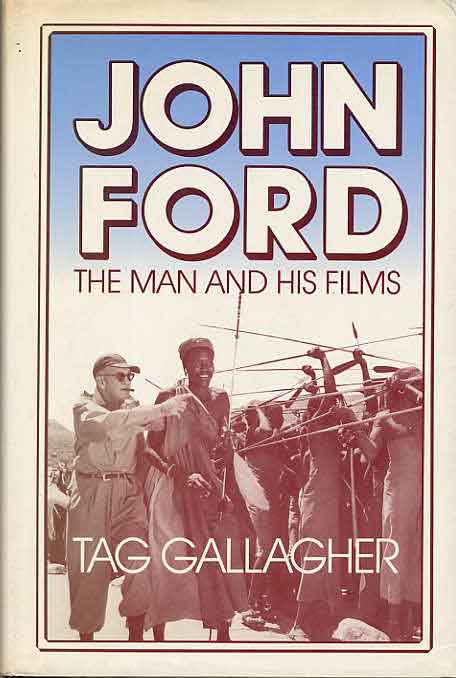

JOHN FORD: The Man and His Films

by Tag Gallagher

University of California Press/$35

‘I shall almost always be wrong, when I conceive of a man’s character as being all of one piece.’ Appearing at the outset of Tag Gallagher’s massive critical biography of Ford, this quotation from Stendhal serves both as apologia and as fair warning to readers hoping to find a unified portrait of its subject. Written over the past two decades, Gallagher’s exasperating yet invaluable compendium of diverse thoughts and data may lack the coherence of previous Ford studies by Anderson, McBride/Wilmington, Place and Sinclair (among others). Yet in its outsized efforts to do justice to the contradictions and complexities of the man and his work, it still offers a range of information and insight that dwarfs all competitors.

For one thing, Gallagher certainly goes beyond his predecessors in contriving to grapple with all the surviving films, most of which he arranges in four periods: The Age of Introspection (1927 35), Age of Idealism (1935-47), Age of Myth (1948-61) and Age of Mortality (1962-65). Believing Ford’s best films (Pilgrimage, Judge Priest, Stagecoach, Young Mr Lincoln, How Green Was My Valley, Wagon Master, The Quiet Man, The Sun Shines Bright, Mogambo, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, The Civil War, Donovan’s Reef and 7 Women) to lie in all four periods, Gallagher is able to tease out a surprising number of threads that recur throughout the oeuvre. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 25, 1999). — J.R.

An Ideal Husband

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Oliver Parker

Written by Oscar Wilde and Parker

With Cate Blanchett, Minnie Driver, Rupert Everett, Julianne Moore, Jeremy Northam, John Wood, Lindsay Duncan, Peter Vaughan, and Jeroen Krabbe.

Reviewing a collection of Oscar Wilde’s critical writings almost 30 years ago, Cyril Connolly made a useful distinction between “Wilde” and “Oscar,” the two sides of the same man. “Wilde is Wilde in these essays and seldom ‘Oscar,'” Connolly noted with justifiable admiration. “The change is beneficial. In some cases he is both: thus The Soul of Man Under Socialism in places seems almost inspired; it is a breath of fresh air in which the idealistic aspects of Socialism (or Christian Democracy) have seldom been so well expressed — in his denunciation of private property for example.

“Then ‘Oscar’ intervenes. ‘There is only one class in the community that thinks more about money than the rich, and that is the poor. The poor can think of nothing else.‘”

Connolly goes on to explain, “When I think of ‘Oscar,’ it is against a background of servants, of butlers announcing him and footmen with salvers, of a hansom cab hired by the day, the driver nodding under his tarpaulin while Wilde and Bosie display far into the night.” Read more

From The Soho News (September 3, 1980). –- J.R.

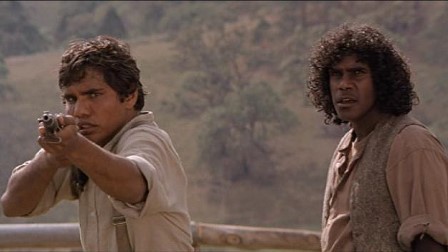

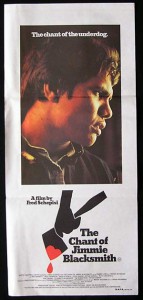

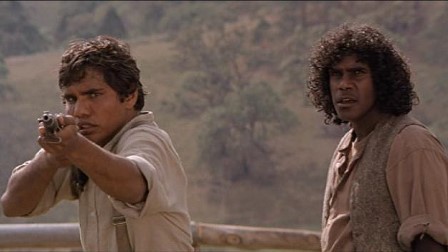

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

Written and directed by Fred Schepisi

Based on the novel by Thomas Keneally

For a good 80 percent or so of its running time, the experience

of seeing The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith affords a

salutary, beautiful shock. Films that are even halfway honest

about racism — Mandingo and Richard Pryor Live in

Concert are the most recent examples that spring to mind

— are so unexpected that they’re often accused of being racist

themselves, perhaps because of the deeply rooted taboos that

they expose and violate.

There’s no question that Fred Schepisi’s powerhouse Australian

movie — adapted from a novel by Thomas Keneally (who plays a

small but significant role as a lecherous cook), and “based on real

events that took place in Australia at the turn of the century”

(just before the federation of Australian colonies) – is agit-prop,

ideologically slanted. But then again, it’s hard to think of any

other current release — including, say, The Empire Strikes

Back and Dressed to Kill -– that isn’t.

The aforementioned hits perform in part the not-so-innocent

task of turning contemporary objects of confusion and disgust

(recent architecture and sex, respectively) into occasions for

exhilarated lyricism. Read more

This article and interview was originally published in the May-June 1973 issue of Film Comment, roughly half a year after the interview took place. I went to work for Tati as a script consultant several weeks after I had the interview, but well before it appeared in print. A few years ago, this piece was reprinted online in the Southern arts magazine Drain. —J.R.

Tati’s Democracy

An Interview and Introduction

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Like all of the very great comics, before making us laugh, Tati creates a universe. A world arranges itself around his character, crystallizes like a supersaturated solution around a grain of salt. Certainly the character created by Tati is funny, but almost accessorily, and in any case always relative to the universe. He can be personally absent from the most comical gags, for M. Hulot is only the metaphysical incarnation of a disorder that is perpetuated long after his passing.

It is regrettable that André Bazin’s seminal essay on Jacques Tati (“M. Hulot et le temps,” 1953, in Qu’est-ce que Ie cinéma? Read more

From Cinema Scope #17 (Winter 2003). Nineteen years later, much of this is clearly out of date, including some of the links, but it seems worth acknowledging that the Internet, like everything else, has a history of its own. — J.R.

I’d like to begin this installment by alerting readers to a couple of excellent online tools that I’ve recently discovered, both of which are indispensable to anyone interested in tracking down the best DVDs of the greatest films: Masters of Cinema and DVD Beaver.

The first of these, at www.masterofcinema.com, is an ongoing international newsletter in English maintained by four rotating editors, with regular updates, devoted to what’s coming out, when and where, and in what condition and with what features. The moment you get to their home page, you see all their regular features, including The News Fountain, a “worldwide DVD calendar” with upcoming releases listed by months, a few discerning articles, and a column of links. The latter is especially valuable, the pièce de résistance comprising a list of directors that at last count included 85 web sites devoted to no less than 76 directors. (In case you’re curious, the directors that have two web sites apiece on this list are Tex Avery, Jean-Luc Godard, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Chuck Jones, Buster Keaton, Akira Kurosawa, Fritz Lang, F.W. Read more

English kitchen-sink realism isn’t ordinarily my cup of tea, but the way Australian writer-director-coproducer Fred Schepisi follows four friends across 40 years creates such a lovely mosaic, acted with such heart, power, and flavor, that I was hooked from the start. It’s a tale anchored around the delivery of a butcher’s ashes to Margate by three of his former pub mates (Tom Courtenay, David Hemmings, Bob Hoskins) and his resentful son (Ray Winstone). Michael Caine plays the butcher in flashbacks, and it’s one of his strongest performances; no less affecting is Helen Mirren as his wife. (I assume the absence of Oscar nominations must have something to do with studio politics.) Adapted from Graham Swift’s Booker Prize-winning novel, this 2001 movie will probably mean the most to viewers old enough to know who Courtenay and Hemmings are and thus to ponder what age has done to their faces, though the actors found to play them and the others in their youth are uncannily persuasive. The personal investments of the lead actors in their parts are palpable; you don’t have to know that Caine is staying in the same hospital where his real-life father (a fish porter) died to recognize that he feels this character down to his marrow. Read more

The following essay was both commissioned and written in early June 2009. My thanks to the Chinese translator Zhanxiong Xu for giving me permission to publish the original English version here.

I’m also pleased to announce that a Chinese translation and edition of one of my own books, Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See, came out in China. I strongly suspect that the subsequent influx of Chinese visitors to this site must have had something to do with its publication. — J.R.

Introduction to the Chinese Edition of More Than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

I

“The Chinese don’t accord much importance to things of the past,” Maggie Cheung maintained in an interview with a French magazine roughly a decade ago (1), “whether it’s films, heritage, or even clothes or furniture. In Asia nothing is preserved, turning towards the past is regarded as stupid, aberrant.”

Interestingly, this statement helps to explain why so many of the most important Chinese films, at least for me, are concerned with the discovery of history, and represent various attempts to reclaim a lost past. I’ll restrict myself to a short list of a dozen favorite Chinese features, all of which exhibit these traits: Fei Mu’s Xiao cheng zhi chun (Spring in a Small Town, 1948); Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Bei qing cheng shi (City of Sadness, 1989) and Xi meng ren sheng (The Puppetmaster, 1993); Wong Kar-wai’s A Fei zheng chuan (Days of Being Wild, 1990) and Fa yeung nin wa (In the Mood for Love, 2000); Edward Yang’s Gu ling jie shao nian sha ren shi jian (A Brighter Summer Day, 1991); Stanley Kwan’s Ruan Lingyu (1992); Tian Zhuangzhuang’s Lan feng zheng (The Blue Kite, 1993); Li Shaohong’s Hong fen (Blush, 1994); and Jia Zhangke’s Zhantai (Platform, 2000), Sanxia Haoren (Still Life, 2006), and Er shi si cheng ji (24 City, 2008). Read more

![Mr. Coconut[DVDRip] 450c5e100a576972b5dc85c0a24988d7 Mr. Coconut[DVDRip]](http://img.emuleday.com/data/img/45/450c5e100a576972b5dc85c0a24988d7.jpg)