From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1976, Vol. 43, No. 504. — J.R.

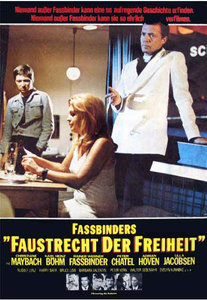

Faustrecht der Freiheit (Fox)

West Germany, 1975

Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Ce r t–X. dist–Cinegate. p.c–Tango-Film. p–Rainer Werner Fassbinder. p. manager–Christian Hohoff. asst. d–Irm Hermann. sc—Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Christian Hohoff. ph–Mictrael Ballhaus. col–Eastman Colour. ed–Thea Eymèsz. a.d–Kurt Raab. m–Peer Raben. songs–“One Night” by Pearl King, Dave Bartholomew, performed by Elvis Presley; “Bird on the Wire” by and performed by Leonard Cohen. l.p–Rainer Werner Fassbinder (“Fox” Franz Biberkopf), Peter Chatel (Eugen Theiss), Karl- Heinz Böhm (Max), Harry Bär (Philip), Adrian Hoven (Eugen’s Father), Ulla Jacobsen (Eugen’s Mother), Christiane Maybach (Hedwig), Peter Kern (Florist “Fatty” Schmidt), Hans Zandler (Man in Bar), Kurt Raab (Barman Springer),Irm Hermann (Mlle. Chérie de Paris), Barbara Valentin (Max’s Wife), Walter Sedlmayr (Car Dealer), Ingrid Caven (Singer in Bar), (El Hedi Ben Salem (Moroccan), Brigitte Mira (Shopkeeper),Bruce Low (Soldier), Ursula Strätz, Elma Karlowa, Evelyn Künneke, Marquart Bohm, Liselone Eder, Klaus Löwitsch.

11,077 ft. 123 mins. Subtitles.

“Fox” Franz Biberkopf, a carnival sideshow performer, loses his job and his lover Klaus (who runs the show) when the latter is arrested. He visits his sister Hedwig, before being picked up by a gay antique dealer Max, and then wins 500,000 marks in a lottery. Scoffed at by Max’s upper-class friends for his proletarian manners, he is nevertheless taken home by one of them. Eugea Theiss, the son of the alcoholic owner of a bookbinding firm on the edge of, bankruptcy. Max advises Fox to invest in the Theiss company, and he subsequently lends the firm 100,000 marks. He and Eugen take a flat together, which Fox purchases for about 150,000 marks, with furniture supplied by Max for 80,000 more, new clothes for both of them, and an expensive car; Fox also lends 30,000 marks to Klaus, now out on parole. Alienated by Eugen’s efforts to ‘educate’ him culturally and defensive when Hedwig’s drunken behaviour disrupts a party for Eugen’s friends, Fox finances a holiday for himself and Eugen in Marrakech, but the two are estranged even further when they quarrel after picking up an Arab and are prevented from taking him to their hotel room.

Back in Germany, Fox signs his flat over to the Theiss firm as security for a loan needed in a business crisis. More miserable than ever after committing a blunder at work which costs the firm 150,000 marks, made to feel stupid by Eugen and his parents, and hurt by Eugen’s flagging interest in him, Fox grows ill and sees a doctor who prescribes valium. When he suggests to Eugen that they split up, he learns to his horror that Eugen has assumed ownership of the flat, that the 5,000 marks he received regularly from the firm was repayment of the loan rather than wages, and that he is virtually dispossessed. After being berated by acquaintances at the gay bar where he hangs out, and by Hedwig (who has to pay for the delivery of his things after Eugen changes the lock on the flat), he dies of an overdose of valium in a shopping mall. Max and Klaus approach discussing a business deal, recognise the corpse and hurry away. Two boys set about picking Fox’s pockets.

“After seeing Douglas Sirk’s films I am more convinced than ever that love is the best, most insidious, most effective instrument of social repression”. This central insight, from an article written by Fassbinder five years ago, has informed a substantial amount of his prolific work, including all four of his features so far released in England. Sustaining it with the dramaturgy of Hollywood soap opera — glazed over with irony and formalised in a narrow repertory of visual and narrative strategies — he has been devoted to social reform and the perpetuation (through updating) of the dominant codes of narrative cinema. Far from being ‘”radical” or “subversive”, as has often been claimed, his cinema is liberal in the best and most hallowed sense of the word — a more honourable version of the project that Stanley Kramer was myopically pursuing with less wit and talent in the Fifties, and a far cry from the subversion of forms to be found in commercial directors as diverse as Mizoguchi, Tati and Buñuel. In Faustrecht der Freiheit — working with narrative elements traceable back to Stroheim and von Sternberg as well as Sirk — he is relating a fable of class exploitation within a homosexual milieu that is rather obvious and predictable in overall design, but clever and nuanced in many of its individual details. The cultural snobbery of Eugen, his parents and his friends is underlined far past the point of necessity or plausibility (leading to a howler when his mother describes seeing the Firebird Suite at the opera), and some of the eventual cruelties of the clan similarly seem too clearly designed to ram home a thesis. But on the other hand, the actual movement of the money is delineated with refreshing sharpness. Fox’s precise expenditures during his doomed career are charted with the rigour and vulgarity of a Balzac, and render each expression of his love for Eugen — subtly prompted in each case by the latter, who is meanwhile blocking off most of Fox’s other means of expression — at once a step further into gaudy Hollywood fantasy and another nail in his proletarian coffin. The centrepiece of this process is the lovers’ visit to a boutique — which Roger Greenspun has perceptively compared to “the public drama of dressing and posing” in Le Amiche — where a coquettish blend of personal styles and Hollywood tropes (romantic piano and strings on the soundtrack, Eugen and Philip caught in a ceiling mirror stealing a furtive kiss, a customer trying on velvet) distil the essence of the world that taunts Fox with its vanities and petty cruelties.

Gullible from the word go and scarcely the master of a destiny that seems sealed before the end of the first reel (with the camera stationed at a low angle before he trips and falls near a lottery counter), Fox is a sentimental victim of no mean proportions, and Fassbinder’s casting of himself in the part against type has the advantage of making the role somewhat more palatable: an unromantic hero if ever there was one (in contrast to Peter Chatel, who always seems ready to step into Camille), he brings some rudimentary counterpoint to the fable through the sheer unwholesomeness of his appearance. And the film is well served overall by Fassbinder’s reliable company of players, with particularly striking performances from Peter Kern as a sorrowful florist and Karl-Heinz Böhm as Fox’s Mephistopheles, who glowers to best advantage in the film’s most oddly stylised scene — a walk taken by Eugen and Fox down the ramp of an enclosed shopping mall of blue-tile pillars and walls where Fox subsequently meets his death. Watching intently, then trailing behind while Fox suggests the termination of the affair, and finally placing his hand on Fox’s head after he moans, “I only want to be the way I used to be”, and Eugen steps over to a pinball machine — thereby locking the composition into an eerie tableau — the sinister Max finally comes to seem a much closer surrogate for the writer-director than the figure of Fox himself.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM