There’s a particular Parisian tradition that seems peculiar to French aesthetics involving a certain license to behave like a depraved lunatic and receive approval, endorsement, and other cultural rewards in return for this boorishness.(Many years back I tried writing about this subject, in a long review of My Life and Times with Antonin Artaud.) I suppose one very bourgeois way of describing this tendency would be to call it the aesthetics of self-indulgence combined with a gift for self-promotion, and though I don’t know French literature well enough to determine what poets might have established this trend (apart from such relatively modern figures as Baudelaire and Rimbaud), there’s no question that Jean Cocteau set down many of the terms and conditions of this tradition in cinema, along with the visiting Spaniards Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali — including, perhaps, a special talent for hustling up various forms of patronage.

Even though not all artists with these characteristics are French, much less Parisian, it could perhaps be argued that those who are commonly celebrated for these traits are typically appreciated either by French critics (Nicole Brenez writing about Abel Ferrara) or Francophile critics (such as Adrian Martin writing about Philippe Grandrieux, among many others). I share some of their taste for this kind of aggressive provocation and exalted excess while another part of me, at least part of the time, tends to stand outside this predilection and question it a little.

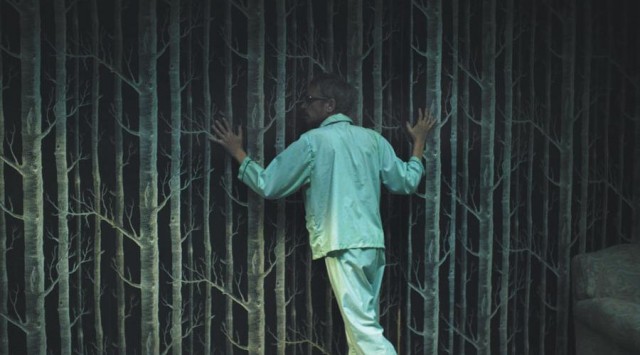

Leos Carax (Les Amants du Pont-Neuf, Holy Motors) clearly belongs to this tradition, as does Philippe Garrel (Les Amants Réguliers) before him. One reason why I tend to prefer Carax to Garrel is a punklike politics that takes some of his bratty attitudes beyond self-absorption, even though autobiography continues to play a very pronounced role, making it necessary at times to decode some of the works via personal references. (The fact that Carax defiantly remains a chain smoker nowadays, as is made clear in a few recent interviews, thus has to be read into the chain-smoking of his brilliant actor-surrogate Denis Lavant in Holy Motors, and it also becomes important to know that it is Carax himself and not Lavant who appears in the film’s mournful, cinephiliac prologue [see first photo below] — although one can easily miss this, as J. Hoberman did and I did myself until I checked back with the interviews.) And cross-references between Carax’s own films become equally important — not only the body language of Lavant (making all of Carax’s films apart from Pola X works that probably deserve to be cosigned by his lead actor), but also the use of Samaritaine in Holy Motors, which incidentally overlooks Pont-Neuf, the central location in Carax’s best film.)

Still another factor distinguishing Carax from Garrel is the former’s all-pervasive cinephilia — making each successive “act” or performance of Lavant in Holy Motors another derisive or sarcastic gesture aimed at digitalized contemporary cinema, an early shot of a cinema audience a reference to the final shot of King Vidor’s The Crowd, the last appearance of Édith Scob [see second photo below] a direct reference to her career-defining role in Georges Franju’s Les Yeux Sans Visage [see third photo below], and perhaps even the final dialogue between stretch limos a conceit inspired by the deleted prologue to Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard — reportedly laughed off the screen at a preview — in which the various corpses in a morgue converse. (More generally, one of the saving graces to this film’s pervasive melancholy is its flashes of angry wit; my favorite movie gag of the year is Carax’s version of Père Lachaise cemetery, where every tombstone declares, “Visitez mon site.”)

The political incorrectness of Carax’s The Lovers of Pont-Neuf and Merde (his contribution to the recent Tokyo!) may have something to do with why those remain my two favorite Carax films to date, although I’m sure I could come up with plenty of equivalents in his four other longer films (Boy Meets Girl, Mauvais sang, Pola X, and Holy Motors — e.g., the “poetic” treatment of AIDS in the second of these). But it’s worth recalling that the celebration of grossly uncouth and unmotivated street violence in Merde, virtually reprised in Holy Motors, is little more than an extended riff on Le Testament de Docteur Cordelier, a lesser-known effort by that often-sentimentalized humanist Jean Renoir, a film which is itself a kind of variation on Renoir’s own, much earlier Boudu sauvé des eaux. [10-16-12]