I wrote the Preface to this 1973 article in 2009 for its eventual reprinting in Kazan Revisited, edited by Lisa Dombrowski (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011). Note (early 2013): My favorite Kazan film, Wild River, has been released on Blu-Ray, and it looks better than ever. — J.R.

Preface (2009): Rereading this essay 36 years after I wrote it for Richard Roud’s two-volume critical collection, Cinema: A Critical Dictionary – The Major Filmmakers (New York/The Viking Press, 1980), I can’t say that many of my positions or preferences regarding Kazan’s work have changed. But in a few cases I’ve been able to amplify some of my original impressions. For my 2007 essay “Southern Movies, Actual and Fanciful: A Personal Survey” (to be reprinted in my 2010 University of Chicago Press collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephila), for instance, I discovered that Kazan hired speech consultant Margaret Lamkin for his stage production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and then again for Baby Doll, to ensure that all the southern accents heard were letter-perfect. And the significance of Kazan having given the names of former friends or colleagues to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952 — not in 1954, as my article stated — became a more prominent feature in his career profile when he was given a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999, almost half a century later, from the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences. Read more

This appeared in the August 22, 2003 Chicago Reader, and has more recently been reprinted in the excellent Camera Lucida. On the afternoon of September 17, 2014, in Sarajevo at the Film.Factory, I screened this for the MA students and assigned them to create five-minute remakes. We screened most of the results nine days later at a party, and they were really dazzling — and all quite different from one another. — J.R.

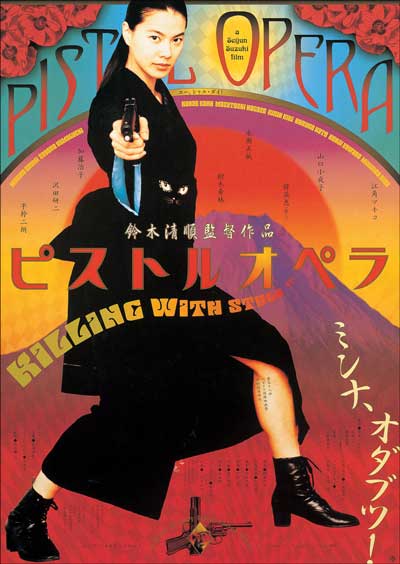

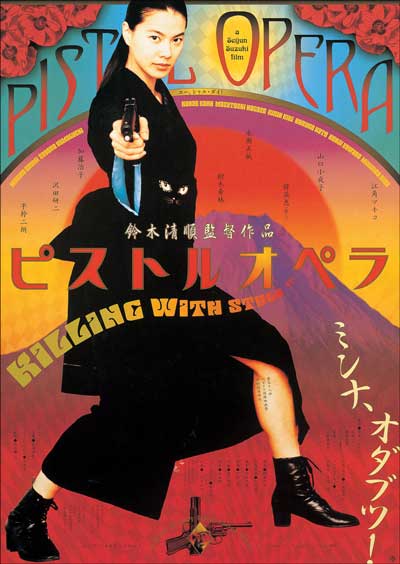

Pistol Opera

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Written by Kazunori Ito and Takeo Kimura

With Makiko Esumi, Sayoko Yamaguchi, Masatoshi Nagase, Kan Hanae, Mikijiro Hira, Kirin Kiki, Haruko Kato, Yeong-he-Han, and Jan Woudstra.

Can I call a film a masterpiece without being sure that I understand it? I think so, since understanding is always relative and less than clear-cut. Look long enough at the apparent meaning of any conventional work — past the illusion of narrative continuity that persuades us to overlook anomalies, breaks, fissures, and other distractions we can’t process — and it usually becomes elusive. Yet it’s also true that we have different ways of comprehending meaning. I once watched some children listen to passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, possibly the most impenetrable book in the English language, and saw them burst into giggles, plainly understanding better than the adults that this was exactly the way grown-ups talked, only funnier. Read more

The following was commissioned by and written for Asia’s 100 Films, a volume edited for the 20th Busan International Film Festival (1-10 October 2015). — J.R.

To explain why Lee Chang-dong’s extraordinary Poetry (2010) is my favorite Korean film, I first need to confess to a feeling of alienation from a good many other South Korean films and what I regard as their excessive reliance on rape and serial killers as subjects. Admittedly, these themes are by no means restricted to South Korean cinema or even more generally to Asian cinema, but they also help to account to my resistance to such highly praised European touchstones involving rape as Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring and Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers (both 1960), and such American films regarding serial killers as Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Ethan and Joel Coen’s No Country for Old Men (2007). The tendency of all these films to exploit and/or sentimentalize these subjects is scrupulously avoided by Lee and handled throughout with tact, delicacy, and a finely nuanced sense of development in its heroine’s ethical and aesthetic consciousness. Consequently, Poetry offers a profound social critique by addressing the theme of rape and its role in Korean society quite directly,

The film centers on the suicide by drowning of a suburban, small-town schoolgirl who had been raped by several of her teenage classmates. Read more

How film history gets rewritten

I realize it must sound crazy for people who haven’t seen Jacques Rivette’s 750-minute Out 1 (1971) or his 255-minute Out 1: Spectre (1972) to keep reading blog posts about them — even though I keep hearing almost every day from various others who have seen either or both films recently, in Chicago or New York or Vancouver or Berkeley, and are still recovering from the experience.

What I’d like to focus on here is how these films wind up getting misrepresented due to the circulation of incomplete data. For instance, everyone who’s seen any stills from the two films and hasn’t seen the films probably concludes that they’re both in black and white. They’re wrong; the problem is that the only photos available from the films on the Internet and in film magazines are in black and white, undoubtedly because color stills would cost too much money to process. In fact, the beautiful restoration of Spectre that showed at the Gene Siskel Film Center last Saturday, blown up from 16-millimeter to 35, had far more luscious and luminous colors than any other print I’ve ever seen — finally justifying Rivette’s supposedly extravagant claim in a 1975 interview that “you might almost say that I am trying to bring back the old MGM Technicolor!

Read more

From Cinema Scope #16 (Fall 2003). — J.R.

One of the more fascinating things about the linguistic options of DVDs in relation to their nationality is how often they confound expectations. It would appear that few countries show more indifference to other countries and their languages than the U.S., yet the DVDs with the greatest number of subtitling and dubbing options are often those on American labels. Conversely, when I visited Japan twice in the late 1990s, I was impressed by the cottage industries devoted to teaching foreign languages, which ranged from prime-time TV shows teaching conversational “business” English and Spanish to bilingual movie scripts sold in bookstores, some of them packaged with videos of the same films. But my recent efforts to hunt for Japanese DVDs with English or French subtitles have been in vain -— which is all the more frustrating when I come across listings for box sets devoted to Kiarostami and Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinéma.

Attending Cinema Ritrovato, an archival film festival, in Bologna last summer, I went hunting for Italian DVDs and quickly discovered that those with Italian movies almost never come equipped with English subtitles (the restoration of The Leopard, which I noted in my last column, is a rare exception). Read more

Into Barbarism

The following is an edited transcript of remarks delivered by Jonathan Rosenbaum at High Concept Laboratories in Chicago on June 5, 2014. Mr. Rosenbaum and the other two panelists were asked to respond to The Point’s issue 8 editorial on the new humanities.

●

I’m the odd person out in this gathering because I’m not an academic, although I teach periodically in various, most often relatively unacademic, situations. And plus, I could be described as a failed academic. Before I came to Chicago I was teaching for four years at the University of California, Santa Barbara, but prior to that I actually began my failed academic career in the U.S. where Robert Pippin had his background, at UC San Diego. And in between I was an adjunct at NYU, at the School of Visual Arts, etc.

My academic background, actually, was in English. I was an English major as an undergraduate and in graduate school I did everything but a dissertation in English and American literature. But then I went to Europe and ended up being a journalist. And the reason why is that I had reached the point of alienation in graduate school where I was actually making a point of reading college outlines rather than the literary texts because I didn’t want them ruined — I wanted to read them in my own time, whereas what they needed in terms of my papers could better be fulfilled by reading the college outlines than by actually reading the texts. Read more

Written for Criterion’s laserdisc release of Parade and apparently posted on its web site (criterion.com) — at least if it had a web site that early — on March 31, 1991. — J.R.

It seems incredible that it’s taken seventeen years for a film as truly great as Parade — Jacques Tati’s final work — to become available in the U.S., and that it’s reaching the public, for the first time, on laserdisc. But old habits die hard, including our biases about technology as well as spectacle. Tati was the first major filmmaker to shoot a feature in video, and he brought to this challenge the same sort of innovative craft that he brought to the movie — although the technical options available in video in 1973 were far from what they are today. He began by shooting with an audience at a circus in Sweden for three days, using four video cameras. Then, he spent 12 days in a studio reshooting portions of the stage acts on film.

The first “gag” in Parade takes place in front of a theater and is so subtle it hardly qualifies as a gag at all. A teenager in line picks up a striped, cone-shaped road marker on the pavement and dons it like a dunce cap; his date laughs, finds another road marker, and does the same thing.

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1993). — J.R.

Bill Murray plays an obnoxious TV weatherman from Pittsburgh forced to relive the same wintry day in a small Pennsylvania town over and over again until he gets it right, in an unexpectedly graceful and well-organized comedy (1993) directed and cowritten by Harold Ramis. While the movie’s underlying message is basically A Christmas Carol strained through It’s a Wonderful Life — hardly a recommendation in my book — the filmmakers mercifully spare us the speeches and simply demonstrate their thesis; as they do they reveal their true virtue: a fluid sense of narrative that works the story’s theme-and-variations idea with a glancing and gliding touch. Considering that none of the characters is fresh or interesting, it’s a commendable achievement that the quality of the storytelling alone keeps the movie watchable and likable. With Andie MacDowell and Chris Elliott. PG, 103 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

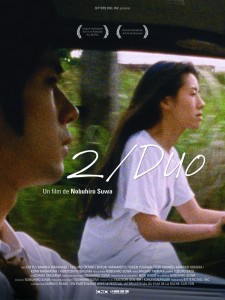

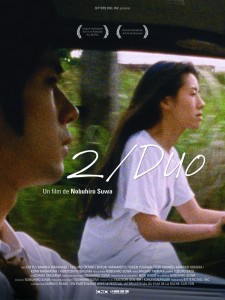

From the February 26, 1999 Chicago Reader. July 2014 postscript: This fascinating and neglected film, still my favorite among the Nobuhiro Suwa features that I’ve seen, has become available on a French DVD released by Capricci — see the first image below — albeit with (optional) French subtitles only. — J.R.

2/Duo

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Nobuhiro Suwa

Written by Suwa, Eri Yu, and Hidetoshi Nishijima

With Yu, Nishijima, and Makiko Watanabe.

The first feature of Nobuhiro Suwa, a director of TV documentaries in his mid-30s, 2/Duo (1996) is the penultimate work in the Doc Films series “Japanese Cinema After the Economic Miracle: Masaki Tamura, Cinematographer.” Having seen only one other film in the series — Shinsuke Ogawa’s remarkable two-and-a-half-hour documentary about the lives of farmers protesting the construction of Japan’s biggest airport, Narita: Heta Village (1973) — I can’t give a comprehensive account of Tamura’s work. But judging from these two very different features, I suspect I might recognize his shooting style without seeing his name in the credits. Though Narita: Heta Village is a documentary and 2/Duo a fictional narrative, the style of both displays a highly intuitive engagement with the characters, expressed most clearly in the way Tamura places and moves his camera in relation to them, neither anticipating their actions nor dogging them, but navigating the spaces they occupy with an intelligence that manages to project empathy as well as independence — a rare combination. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 31, 2001). Today (September 2, 2014), having recently reseen this movie, I’d probably give it a higher rating. — J.R.

The Curse of the Jade Scorpion

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Woody Allen

With Allen, Helen Hunt, Dan Aykroyd, Brian Markinson, Elizabeth Berkley, Charlize Theron, Wallace Shawn, and David Ogden Stiers.

I don’t want to oversell Woody Allen’s 31st feature, which I happen to like. The script is full of holes, most of the one-liners are weak and mechanical, and the plot — a nightclub magician gets two of his hypnotized subjects to steal jewels for him — is so deliberately stupid and contrived that one can probably enjoy it only by pretending it’s a routine, low-budget second feature on an old-fashioned double bill, which is obviously what Allen intended. Yet it’s possible for a picture to be not very good and still be likable — something that doesn’t happen very often for me with Allen’s pictures. (It happened, momentarily, in Everyone Says I Love You — when Allen exposed his vulnerability by singing the first 16 bars of “I’m Thru With Love.”)

The problem with most escapism nowadays is that even if it makes you forget who and where you are, it doesn’t really detach you from norms of the world you’re living in. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 10, 2004). I think I underrated The Five Obstructions, which I now regard as my probable favorite of von Trier’s films, after having reseen it, remastered, on the DVD recently released by Kino Lorber. One obvious advantage to seeing it on DVD is that Leth’s 1967 short, The Perfect Human, is included in its entirety as an extra, and even though I find it less interesting than the various “remakes” included in The Five Obstructions, finally getting a chance to see it in its entirety makes the Leth and von Trier feature a lot more satisfying and interesting. — J.R.

The Five Obstructions

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Jorgen Leth and Lars von Trier

With Leth, von Trier, Claus Nissen, Maiken Algren, Daniel Hernandez Rodriguez, Vivian Rosa, Patrick Bauchau, and Alexander Vandernoot.

What the Bleep Do We Know?

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Mark Vicente, Betsy Chasse, and William Arntz

Written by Arntz, Chasse, and Matthew Hoffman

With Marlee Matlin, Elaine Hendrix, John Ross Bowie, Robert Bailey Jr., Barry Newman, and Larry Brandenburg.

When is an “experimental film” not an experimental film? This might seem a niggling matter to the ordinary paying customer, but it’s a serious issue for artists who’ve devoted their careers and lives to experimental filmmaking, knowing that they’ve given up the possibility of a wide audience by doing so. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 10. 2005). — J.R.

Cinderella Man

*** (A must see)

Directed by Ron Howard

Written by Cliff Hollingsworth and Akiva Goldman

With Russell Crowe, Renee Zellweger, Paul Giamatti, Craig Bierko, Paddy Considine, Bruce McGill, and Ron Canada

Ron Howard is an exemplar of honorable mediocrity. His films are conventional and stuffed with cliches, but their nice-guy liberalism is more sincere and nuanced than their tropes would lead one to expect. In his better efforts — Night Shift, Far and Away, Parenthood, The Paper, and now Cinderella Man — the sense of conviction is so passionate that the truth behind the cliches periodically emerges.

This is Howard’s first feature since the award-winning A Beautiful Mind, and the storytelling is fluid and gripping. He has plenty of cliches to peddle about boxing and working-class virtues in the midst of deprivation during the Depression, and the visual rhetoric in which he couches those cliches even give them a metaphysical dimension. The decor is as underlit as it is in Million Dollar Baby, and the cinematography’s even more mannerist in fetishizing darkness to project an aura of doom and desperation. In the deftly staged prizefight sequences, Howard goes even further than Clint Eastwood did in rendering subjective impressions in expressionistic terms. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 5, 1999). — J.R.

This neglected feature is one of Samuel Fuller’s most energetic — his own personal favorite, in part because he financed it out of his own pocket and lost every penny (1952). It’s a giddy look at New York journalism in the 1880s that crams together a good many of Fuller’s favorite newspaper stories, legends, and conceits and places them in socko headline type. A principled cigar smoker (Gene Evans) becomes the hard-hitting editor of a new Manhattan daily, where he competes with his former employer (Mary Welch) in a grudge match full of sexual undertones; a man jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge trying to become famous; the Statue of Liberty is given to the U.S. by France, and a newspaper drive raises money for its pedestal. Enthusiasm flows into every nook and cranny of this exceptionally cozy movie; when violence breaks out in the cramped-looking set of the title street, the camera weaves in and out of the buildings as through a sports arena, in a single take. The phrase “Park Row” is repeated incessantly like a crazy mantra, and the overall fervor of this vest-pocket Citizen Kane makes journalism sound like the most exciting activity in the world, even as it turns all its practitioners into members of a Fuller-esque military squad. Read more

From Cinema Scope No. 45, Winter 2011. -– J.R.

As a postscript to and short commentary on the closing section of Ted Fendt’s interview with Luc Moullet in the previous issue of Cinema Scope, l’d like to propose that (a) Moullet’s two most recent shorts, Toujours moins and Chef-d’oeuvre?, provide a kind of summary of Moullet’s work as a whole, by focusing respectively on economy and art, and (b) the second of these actually fuses these two concerns, offering not only a digest of his oeuvre as both a filmmaker and a critic, but also a short manifesto that exalts the importance of shortness itself in relation to his particular talents.

Moullet’s best work as a filmmaker can generally be found in his shorts — which makes it all the more regrettable that the Moullet box set with English subtitles includes only his features, and the sole collection of his shorts on DVD (Luc Moullet en shorts, 2009) is untranslated. The most important exceptions to this rule are Genèse d’un repas (1978), arguably his most profound statement about economy, and Anatomie d’un rapport (1976), but it might be added that many of his other best features, such as Les contrabandières (1968), La comédie du travail (1987), and Parpaillon (1993), are effectively collections of thematically related shorts, while some of his thinnest – – e.g., Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 5, 1990). From the vantage point of 2013, The Wolf of Wall Street might be regarded in certain respects as an inferior remake of GoodFellas, with all the limitations of the original dutifully preserved. — J.R.

GOODFELLAS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese

With Ray Liotta, Joe Pesci, Lorraine Bracco, Robert De Niro, Paul Sorvino, Chuck Low, Frank Sivero, and Debi Mazar.

Greed, indiscipline and amorality drench the money-military culture, in its upper echelons and in its pits. Somebody destroyed the national superego. Does anyone have a plan to make one anew? — from a recent editorial in the Nation

The opening, white-against-black credits of Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas whiz horizontally across the screen to the sounds of traffic in quick, isolated bursts, telling us at the outset that speed is of the essence. Using a cast of almost 150 players (including a delightful performance by Scorsese’s mother Catherine) and a sound track with about 40 pop singles that are both apposite and subtle in the way they comment on the action, Scorsese pushes the narrative along with a sense of gliding motion and legible fluidity that is often breathtaking. Read more