I wrote the Preface to this 1973 article in 2009 for its eventual reprinting in Kazan Revisited, edited by Lisa Dombrowski (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011). Note (early 2013): My favorite Kazan film, Wild River, has been released on Blu-Ray, and it looks better than ever. — J.R.

Preface (2009): Rereading this essay 36 years after I wrote it for Richard Roud’s two-volume critical collection, Cinema: A Critical Dictionary – The Major Filmmakers (New York/The Viking Press, 1980), I can’t say that many of my positions or preferences regarding Kazan’s work have changed. But in a few cases I’ve been able to amplify some of my original impressions. For my 2007 essay “Southern Movies, Actual and Fanciful: A Personal Survey” (to be reprinted in my 2010 University of Chicago Press collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephila), for instance, I discovered that Kazan hired speech consultant Margaret Lamkin for his stage production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and then again for Baby Doll, to ensure that all the southern accents heard were letter-perfect. And the significance of Kazan having given the names of former friends or colleagues to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952 — not in 1954, as my article stated — became a more prominent feature in his career profile when he was given a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999, almost half a century later, from the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences. As controversial as this award was to some Academy members, it seemed to me then — and still seems now — rather hypocritical and myopic to assign more blame to Kazan than to any of the studio executives who actually implemented the Hollywood Blacklist and then kept it going for as long as it lasted, all of whom escaped public censure almost entirely. One of these executives, ironically and quite coincidentally, was Louis B. Mayer, the model for the villain played by Robert Mitchum in Kazan’s last feature, The Last Tycoon (1976).

This film was even more of an anticlimax and letdown than its underexposed predecessor, The Visitors (1972). There’s an emblematic dialectic between these last two features, suggesting some of the span of Kazan’s career — a personal, low-budget independent film and contemporary story, shot with unknowns in and around the Connecticut homes of Kazan and his son, followed by an impersonal, glossy studio package with a period setting, dripping with big names and shot on soundstages. To find rough counterparts in the first part of Kazan’s career, one would probably have to reach for Boomerang! and Sea of Grass (both in 1947, though made in the reverse order). But the faltering scripts in these last two films — overly didactic in the first case, shapeless in the second — give them both the status of postscripts to Kazan’s best work, so it still seems appropriate for me to have ended my 1973 discussion of his career with Wild River (1960).

As an unfinished novel, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon steadily loses focus and coherence as it proceeds, and even if one accepts its curious idolatry of MGM producer Irving Thalberg as a role model, it’s arguably inferior both as literature and as local portraiture to the two other major Hollywood novels written during the same period, What Makes Sammy Run? and The Day of the Locust. So it isn’t surprising that the Kazan film, saddled with a sprawling Harold Pinter script that Kazan chose not to alter, never finds any secure footing, shedding its few virtues along the way. (Chiefly these are the finely tuned lead performance of Robert De Niro as Monroe Stahr, Kazan’s own choice for the role, and an unusually intense one from Tony Curtis as one of the producer’s leading players — along with a few incidental moments, such as a lingering closeup of Theresa Russell as a smitten college girl as she’s leaving Stahr’s office.) But the excellent Don Mankiewicz adaptation directed by John Frankenheimer for Playhouse 90 in 1957 [see below] proves that it needn’t necessarily have turned out that way, if Kazan had figured out some way of engaging with the material. The problem, as he admitted in his autobiography, was that his motivation for taking on this project had little to do with its own merits and a great deal to do with improving the health of his mortally ill mother by moving her to southern California — a ploy that incidentally didn’t succeed.

Although I didn’t mention it at the time, I was lucky to have seen three of Kazan’s stage productions during the late 50s — The Dark at the Top of the Stairs (1957), J.B. (1958), and Sweet Bird of Youth (1959) — and still regard the third of these as one of his key achievements, far more important than any of the five features he directed after Wild River. (Splendor in the Grass is still highly regarded in some quarters, but for me it’s severely limited by the hectoring simple-mindedness of its script and its stereotypical characters. Perhaps the only films scripted by or adapted from William Inge to have comfortably outlived their own periods are Picnic and Bus Stop, in both cases mainly because of their casts and crews.)

Furthermore, while I’m intrigued by the assertion of Robert Cornfield, the editor of the 2009 collection Kazan on Directing (New York; Alfred A. Knopf), that “Kazan’s rise to directorial preeminence coincided with a crucial psychic shift in American culture. Between 1945 and 1955, the per capita American income nearly tripled, the greatest increase in individual wealth in the history of Western civilization,” I would also link the peaking of Kazan’s talent during the 50s, like that of his friend Nicholas Ray, to his experiences during the 30s — the period when he first encountered filmmaking through his work on the leftist shorts Pie in the Sky (1935) and People of the Cumberland (1937) –- which ultimately made Wild River the logical culmination of his filmography. Ironically, The Last Tycoon is also set during the 30s, but this was the converse of the kind of 30s that Kazan knew and understood first-hand.

J.R., 2009

***

To view Kazan’s development as either a progression or a regression is to assign a system to one of the most unsystematic careers in the American cinema. Even to regard his work as a totality is difficult, because the rules keep changing: how does one link A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945) with The Visitors (1972) — made over a quarter of a century apart — or Wild River with Splendor in the Grass, shot successively in 1960 and 1961?

Confronted with an extremely varied and uneven body of work, one is irresistibly drawn to the solace of formulas. In his conscientious, thoughtful study of Kazan (born 1909) in the Seghers series Roger Tailleur proposes a gradual movement from “third” to “second” to “first” person — a plausible enough theory, particularly when one comes to the later films, although Kazan seems to contradict it in an interview when he asserts that The Arrangement (1969) is “about Judith Crist’s neighbor or Vincent Canby’s cousin…[it’s] about you, ya sonovabitch, in your button-down shirt!” Andrew Sarris remarked in The American Cinema, more rhetorically than accurately, that “the Method of A Streetcar Named Desire has finally degenerated into the madness of Splendor in the Grass,” when in fact, whatever position one takes towards either film, there is plenty of Method and madness in both of them.

Considering Kazan’s status as an auteur, it is worth recalling that he was widely recognized as the equivalent of one for his work on the stage throughout the late ‘40s and ‘50s — a man who persuaded Tennessee Williams to rewrite the ending of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and was believed to have played an important role in molding the conceptions of A Streetcar Named Desire and Death of a Salesman. It was observed more than once during the ‘50s that love had a magical way of stepping in and solving most of the characters’ problems in the last acts of Kazan-directed plays, notably Tea and Sympathy, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Dark at the Top of the Stairs and J.B. — a recourse to a deus ex vagina was one wag’s way of putting it. Ironically, there is a curious reticence in Kazan’s handling of sex in films made during the same period: an unusual amount of tact is shown about the hero’s extracurricular sex life in East of Eden (1955); in Baby Doll (1956) a central ellipsis makes it impossible to know whether the heroine and the Sicilian ever sleep together; and in Splendor in the Grass the prostitute sent to the hero’s hotel room abruptly disappears — in what looks like an editing error — before we can discover if they actually have had sex. By contrast, the transition from a broken mirror to a hose washing away trash in A Streetcar Named Desire (1952), to stand for Stanley Kowalski’s rape of Blanche DuBois, seems all too explicit.

As an indication of Kazan’s reputation as a creative force, even a critic as unaccustomed to hyperbole as Eric Bentley wrote in 1953 that “the work of Elia Kazan means more to the American theatre than that of any current writer whatsoever.”

As the principal liaison between the students and techniques of Actors’ Studio and the American cinema, Kazan’s contribution and influence have been decisive; apart from “discovering” James Dean, Zohra Lampert, Jack Palance, Lee Remick, and Jo Van Fleet, among many others, he has directed some of the best performances ever recorded on film. His location shooting, which began with Boomerang! in 1947, and his sensitive use of local inhabitants, has given some of his films an authenticity of regional flavor which is rare in American films. In striking contrast to the sloppy approximations in such films as Richard Brooks’ Sweet Bird of Youth, Robert Mulligan’s To Kill a Mockingbird, John Frankenheimer’s I Walk the Line, and Sydney Pollack’s This Property Is Condemned, which can only make a native Southerner wince, the accents and background detail in Kazan’s four excursions into the Deep South — New Orleans (Panic in the Streets, 1950), rural Mississippi (Baby Doll), rural Arkansas and Memphis (A Face in the Crowd, 1957) and the Tennessee Valley (Wild River) — are unparalleled in their accuracy; the only comparable example that comes to mind is Phil Karlson’s The Phenix City Story. (Pinky, 1949, and A Streetcar Named Desire, on the other hand, were both studio-shot, and look it.)

Despite these achievements, Kazan’s work generally reflects and encourages equally scant amounts of critical detachment. Even in his most questionable enterprises Kazan can usually squeeze out the maximum amount of heat and tension implicit in any material. But if his talents are ultimately at the mercy of this material, how much of our response is dictated not by his abilities but by the material he is using?

Seen during adolescence, East of Eden (from John Steinbeck’s novel) might be mistaken for naturalism; at a later age, it is likelier to look like expressionism; but how does one judge it “objectively?” A film which, like its youthful hero, cries out for indulgence and sympathy, and offers a dazzling if spastic fireworks display in return, it is an experience designed to be undergone, not an object to be contemplated; and one cannot look at that experience without turning it into an object. Like most of Kazan’s films, it thinks with its guts, and it leaves one exhausted, but not wiser. When Cal (James Dean) is violently dragged from his mother’s presence down a dark, narrow hallway in her whorehouse, screaming his protest and pleading while he grasps a rail so tightly that the pimp pulling him tears off half his sweater, the important thing is not that we are witnessing a symbolic birth trauma, but that Kazan is doing everything he can to make us believe that we are experiencing a real one. The tortured postures of Dean, as angular as those in Caligari; the stark lighting and composition; the burst of highly-charged anguish from Leonard Rosenman’s score and the exaggerated sounds of the violence; the pimp not just any pimp but Timothy Carey, the quintessential B-film creep; the hyperbolical whoriness of the bar at one end of the hall, the overwrought anger of the mother (Jo Van Fleet) at the other — one either capitulates before it all or rejects it as mad excess, but one can hardly sit there and watch it dispassionately.

East of Eden has been criticized for such “stylistic aberrations” as the tilted angles in two scenes between Cal and Adam (Raymond Massey) and a camera movement following Cal back and forth on a swing, but surely these innovative uses of the CinemaScope format are motivated first of all by the extravagance of Dean’s performance; the camera’s function is merely to set off this spectacle as sympathetically and dynamically as possible. From the opening pan that connects Jo Van Fleet crossing a road to Dean sitting on a curb, the camera remains totally at the service of the actors. With the help of Paul Osborn’s script, Dean, Van Fleet, Massey, Julie Harris, and Burl Ives all create characters who seem to extend beyond the confines of the story, lending a certain verisimilitude to what is essentially an adolescent fantasy. Certainly one’s responses are largely determined by how much sympathy one has with the emotional bias given to Cal; if the spectator feels “closer” (by age or temperament) to Adam — and Massey’s rich portrayal obviously permits this — the film is bound to be more than a little irritating.

Similarly, one suspects that On the Waterfront (1954) falters in its final section mainly because it is impossible for most spectators to feel, as Kazan and Budd Schulberg (who wrote the screenplay) apparently did, that the hero’s status as an informer justifies the radical foreshortening of his character from a complex human being — perhaps Marlon Brando’s densest and most fully realized role — to an icon of a suffering Christ. Admittedly, this notion is a logical culmination of the “individual versus the mob” theme that informs the film from the outset, observable even in the contrasts in Leonard Bernstein’s score — a solo French horn (heroic) behind the credits, stormy percussion (threatening) behind the opening scene. But confronted with the brilliance of Brando’s performance — largely a matter of details having little to do with this theme, like his gesture of trying on Eva Marie Saint’s glove in their first long scene together — it is difficult not to feel that this notion is finally bent out of shape; and unless one is as obsessed with the idea of informing as the film implies one ought to be, the final emphasis is bound to seem somewhat false and misleading—a drastic over-simplification of most of the issues involved. (East of Eden, it should be noted, ends with some less than convincing piety of its own, when Adam’s bedroom is lit in such a way that it suggests a cathedral.)

On the basis of interviews and other external evidence, it is evident that East of Eden and On the Waterfront both contain elements that relate quite personally to Kazan — the father-son relationship in the former, the issue of becoming an informer in the latter. (In 1954 Kazan supplied names of former Communist associates to the House Un-American Activities Committee; other “friendly” witnesses included Schulberg and Lee J. Cobb, who acted in On the Waterfront. In The Visitors, scripted by Kazan’s son Chris, informing again becomes a central issue.) Indeed, a particular stylistic emphasis is given to these elements which makes them the pivotal points in each film: Adam’s refusal of Cal’s gift shown in the most extreme of East of Eden’s tilted angles, Terry Malloy’s “confession” — made successively to priest and girl-friend— highlighted by the fact that it is unheard (the first time, the actors walk away from the camera; the second time, a boat whistle covers it up.)

In reviews of East of Eden and Baby Doll, Truffaut suggested that Kazan’s unity was to be found neither in shots nor in films but in scenes, and the longer the scene the better. It is a persuasive idea, and one that helps to explain why Baby Doll survives as one of Kazan’s most controlled and successful works. Built almost exclusively around very long scenes, first between Carroll Baker and Karl Malden, then Baker and Eli Wallach, and then all three together, it sustains its peculiar brand of black comedy until the last scene, when the tone abruptly shifts to bitter-sweet pathos. None of the three leads has ever given a better performance: Malden’s top-heavy puggishness is for once turned into a marvelous comic instrument as he assumes the mulish pride of Archie Lee, Tennessee Williams’ engaging variation on Faulkner’s Jason Compson — a villain we love to hate, whose angry tirades ring like lyrical cadenzas; Wallach, as the sly Sicilian, conveys an icy intensity of “grace under pressure” that suggests enormous reserves of energy; while Baker’s girlish eroticism prefigures, and very likely influenced, the sorts of parts that Tuesday Weld would later expand upon. Possibly because Baby Doll is the least ambitious of Kazan’s mature works (excepting only Panic in the Streets, an expert thriller) and is not burdened, except incidentally, with conveying any profound social or emotional truths, even the most questionable devices — such as the use of local blacks as Greek chorus — are handled with a measured ease which makes them work. Most impressive of all is the lengthy seduction scene staged in and around the crumbling mansion, a virtuoso acting exercise that runs (with brief interruptions and diversions) for nearly an hour.

But if Kazan works best in his longest scenes — usually those, one should add, with only two characters — what are we to make of his more recent films, where the scenes have become progressively shorter and more fragmented, and the overall unity sought is a thematic consistency binding together a mosaic? This trend can already be seen in the scattershot hysteria of A Face in the Crowd, where the montage sequences serve to convey both Schulberg’s simplistic sociological notions (a housewife watching television and declaring, “Ain’t that the truth!“) and the exciting if over-accelerated rise to power of the hillbilly hero. But even more than this film and other earlier works — well-intentioned, offensive nonsense like Gentleman’s Agreement (1948) (Be nice to Gregory Peck because he’s a Gentile playing a Jew) and Pinky (Be nice to Jeanne Crain because she’s playing a black girl playing a white); Cold war agitprop like Viva Zapata! (1952) and Man on a Tightrope (1953); and Manichean psychodramas like On the Waterfront, East of Eden, and Splendor in the Grass — America, America (1963), The Arrangement, and The Visitors are ostentatiously thesis films, and the details seized in individual shots and short scenes are stacked together to support the overriding arguments.

In America, America and The Arrangement — parts I and III of a still unfinished quasi-autobiographical trilogy—the grandness of the conceptions theoretically justifies this procedure; a geographical-cultural density is attempted in the first, a psychological-chronological depth in the second, although even here the best scenes are invariably the longest ones: Stavros’ confession of duplicity to his fiancée in the apartment that has been furnished for their marriage; Eddie and Florence Anderson thrashing out their own marriage in ahotel suite. (Women tend to figure for Kazan, here and elsewhere, as the Great Imponderables, but it is interesting that the best acting in both films generally comes from women, perhaps because they’re allowed a greater range and more leeway.) But if these works take up serious and commanding themes which make them intermittently compelling, they are limited in each case by Kazan’s lack of objective distance from his heroes: Stavros’ monomaniacal wish to get to America is matched only by Kazan’s monomaniacal insistence on the moral duplicity which this requires, repeated in nearly every scene, and scarcely helped by the monotonous performance of Stathis Giallelis, who chiefly dramatizes his dilemma by covering his mouth and glaring intensely. Kazan’s novel The Arrangement, whatever its faults, betrayed an R. D. Laing-influenced concern about the definition of sanity that permitted a searching examination of its hero’s situation; the film reduces this question to such narrow dimensions that the issue of “selling out” begins to center less around Eddie Anderson and more round the question of why Kazan chose to cheapen the most interesting aspects of his own novel.

Fragmentation in The Visitors — principally a matter of cross-cutting between simultaneous scenes — serves mainly to create crude juxtapositions, inhibiting the narrative flow and making the exposition rather laborious. A daring experiment in low-budget, super-16mm shooting that deals with the horror of the Vietnam war and the domestic violence that ensued from it, it features a remarkably strong, believable performance by a non-professional (Steve Railsback as Nickerson) and raises a lot of questions; but too many of these revolve around the film’s own methods and assumptions. Why does the protagonist, who reports the rape and murder of a Vietnamese girl by his fellow soldiers, wait until two of these men turn up for revenge, months later, before telling his girl-friend about the incident? Is the girl’s flirtation with Nickerson credible by any criteria but the most didactic? After establishing the machismo of the visitors and the girl’s father a dozen different ways, to the point of caricature, why push the point even further by underlining that they like their steaks rare, while the informer likes his “nearly burnt?” If the latter truly abhors violence, why does he strike the first blow in his climactic fight with Nickerson? (The same problem turns up elsewhere in Kazan — in East of Eden, when the peace-loving Aaron viciously turns on Cal; more centrally in The Assassins, Kazan’s second novel, when the non-violent hippie hero Michael ends up murdering a sympathetic ally to express his cynicism about social injustice. Are all of Kazan’s “pacifists” imposters?)

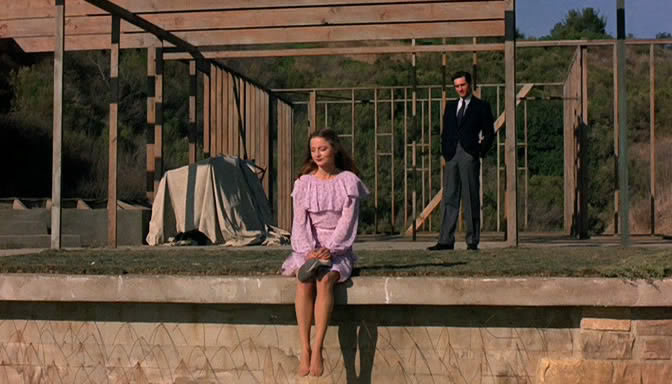

In striking contrast to this garish overkill is the quiet, understated control of Wild River, Kazan’s best film — an elegiac meditation on the relationship between social progress (the construction of a T.V.A. dam in the late ‘30s) and individual intransigence (the refusal of an old woman, Ella Garth, to vacate her premises before her island is flooded), including the most complex and finely detailed love story in all Kazan’s work. Here one finds an editing style that succeeds beautifully in expressing and amplifying the theme: by continually cutting from medium shots to long shots, Kazan moves from considering the characters on their own terms to situating them in the natural settings which help to identify them — the land, fields, buildings, and river which are never only backdrops to the story, but form an integral part of it. As many have noted, the theme and style are quite Fordian; at the end of the first meeting between Chuck (Montgomery Clift), the T.V.A. agent, and Ella (Jo Van Fleet) on the latter’s porch, after her granddaughter Carol (Lee Remick) says to Chuck, “If I was you, I’d go now,” and the family withdraws into the house, Kazan cuts to a long shot of Chuck framed though the closing door that unmistakably echoes the final shot of The Searchers.

In an extended scene between Chuck and Carol the same principle is used differently, to even greater effect. As Carol tries to learn whether Chuck will take her away with him when his job is over, their dialogue is shown in angle/reverse-angle, emphasizing the emotional distance between them by isolating each in separate shots. When Chuck finally indicates that he does intend to leave without her, she starts to cry, at which point there is a cut to both of them in a single shot—Carol standing against a wall in the right foreground of the CinemaScope frame, Chuck sitting on the sofa in center background—a transition which, coinciding with Carol’s tears, defines the moment when their separate lives become irrevocably linked.

Paul Osborn, who scripted Wild River as well as East of Eden, and Jo Van Fleet, who makes extraordinary contributions to each, are undoubtedly responsible for much of the distinction of both films, but obviously much credit is due Kazan as well. It is paradoxical that all three collaborated on two works which are so radically different, and which reveal Kazan at his most rhetorically effective and his most classically restrained. From the sensitive directing of Peggy Ann Garner in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn to the spectacular helicopter shots in The Arrangement — two examples out of dozens — the films of Kazan are full of isolated achievements. But Wild River represents an isolated achievement of its own: a masterful integration of the social with the personal, the romantic with the practical, the historical with the contemporary, the subjective with the objective, the local with the universal — a fusion of long scenes with a broad vision that creates Kazan’s one achieved masterpiece.