From Sight and Sound (Spring 1987). –- J.R.

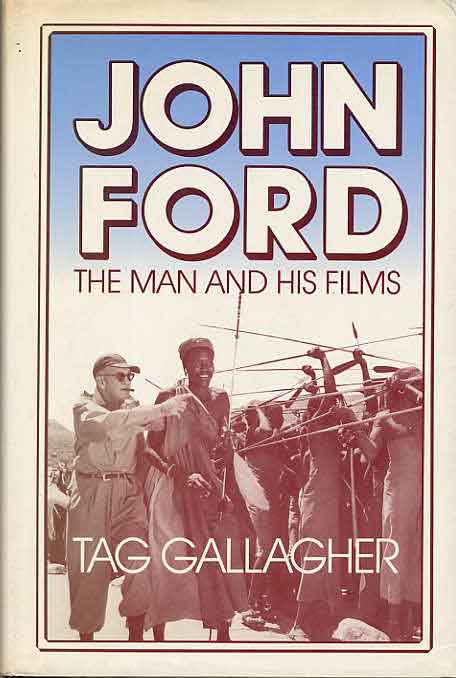

JOHN FORD: The Man and His Films

by Tag Gallagher

University of California Press/$35

‘I shall almost always be wrong, when I conceive of a man’s character as being all of one piece.’ Appearing at the outset of Tag Gallagher’s massive critical biography of Ford, this quotation from Stendhal serves both as apologia and as fair warning to readers hoping to find a unified portrait of its subject. Written over the past two decades, Gallagher’s exasperating yet invaluable compendium of diverse thoughts and data may lack the coherence of previous Ford studies by Anderson, McBride/Wilmington, Place and Sinclair (among others). Yet in its outsized efforts to do justice to the contradictions and complexities of the man and his work, it still offers a range of information and insight that dwarfs all competitors.

For one thing, Gallagher certainly goes beyond his predecessors in contriving to grapple with all the surviving films, most of which he arranges in four periods: The Age of Introspection (1927 35), Age of Idealism (1935-47), Age of Myth (1948-61) and Age of Mortality (1962-65). Believing Ford’s best films (Pilgrimage, Judge Priest, Stagecoach, Young Mr Lincoln, How Green Was My Valley, Wagon Master, The Quiet Man, The Sun Shines Bright, Mogambo, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, The Civil War, Donovan’s Reef and 7 Women) to lie in all four periods, Gallagher is able to tease out a surprising number of threads that recur throughout the oeuvre. A glance at his index reveals more than sixty themes and motifs that are traced through countless films: absent family members, Boston, brawls, dances, doctors, flowers, fools, graves, Indians, lanterns, lawyers, parades, prostitutes, rivers and weddings comprise only a sampling. (Boston, we learn, has basically negative connotations for Ford in My Darling Clementine, Fort Apache, The Last Hurrah, Donovan’s Reef and 7 Women, characteristically signifying chaos and screwballs. Dances are traced through 29 films, flowers through 24, graves through 21, lanterns through a dozen.)

More persuasive about Ford’s mythology than about his shifting and ambivalent politics (which seem to have run the gamut from left to right as fully as Mizoguchi’s), Gallagher devotes a great deal of attention to both. The sense of Ford’s personality which emerges achieves at times a novelistic density. And the films are often seen to reverberate on multiple planes as well: a simple arm gesture made by John Wayne in the last shot of The Searchers is traced all the way back to a signal gesture made by Harry Carey in several early Ford Westerns — an echo given further resonance by the fact that the house Wayne is leaving is that of Mrs Jorgensen, played by Carey’s widow.

All the same, John Ford often presents something of an obstacle course. Like the crotchety Ford he describes, Gallagher himself is a creature of mixed purposes and motives, and in addition to hagiography, gossip, criticism and biography, the book provides Ford’s earnings, the negative costs and domestic grosses on most of his features, the salaries of all the lead actors in Fort Apache, countless production anecdotes and stray details. Much of this information is useful to have, but Gallagher often has trouble distinguishing the pertinent from the incidental, and his scattershot style adds to an overall sense of kitchen sink clutter.

While the book bears witness to the critical debates that have circulated round Ford in relation to Catholicism, history, militarism, patriotism, racism and sexism, it is chiefly grounded in the romantic, transcendental auteurism of the 60s rather than the New Left skepticism about these positions which developed somewhat later. Gallagher devotes considerable space, however, to responding to this skepticism, and comes closer than any other Anglo-American critic to defending Jean-Marie Straub’s description of Ford as Brechtian and dialectical — with films as diverse as Air Mail, Fort Apache, The Quiet Man and Donovan’s Reef offered among the key exhibits. As with the Brechtian Sirk constructed by some British critics in the early 70s, Gallagher’s arguments are not likely to sway viewers more concerned with the popular responses to these films when they first appeared. But there are intriguing suggestions along the way: The Quiet Man as a sociological analysis of Innisfree society; Donovan’s Reef as Ford’s equivalent to The Golden Coach.

Some readers are bound to quarrel with some of the author’s priorities. Mogambo gets almost a dozen pages of close analysis, while Tobacco Road is dismissed in three sentences, and Gallagher is mainly disrespectful of ‘established’ classics such as The Informer, The Grapes of Wrath, The Long Voyage Home and the last two-thirds of the Cavalry trilogy. Sometimes these putdowns seem perfunctory rather than reasoned (‘Those who delight chiefly in the spoken word’ relish The Long Voyage Home, Gallagher notes sniffily, ignoring that it arguably contains Gregg Toland’s best work outside Citizen Kane), and on the whole the book is stronger when the author is sufficiently engaged with a film to describe it in some detail. A generous array of frame enlargements accompany most of the extended analyses. When the prose gets overblown or ungainly, there is usually an attractive or revealing illustration nearby to put things back in perspective.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM