From the Chicago Reader (March 9, 1990). — J.R.

The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it. . . . The individuals composing the ruling class possess among other things consciousness, and therefore think. Insofar, therefore, as they rule as a class and determine the extent and compass of an epoch, it is self-evident that they do this in its whole range, hence among other things rule also as thinkers, as producers of ideas, and regulate the production and distribution of the ideas of their age: thus their ideas are the ruling ideas of the epoch. –Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology (1845-46)

A good many newspapers and magazines have accompanied their reviews of Vineland, Thomas Pynchon’s fourth novel, with the same 37-year-old photograph of the author grinning goofily from his high school yearbook. Given Pynchon’s refusal to be photographed or interviewed, there are touches of both desperation and petty vindictiveness in this compulsion to objectify and visualize, however inadequately, a novelist who chooses to be identified only through his writing. Read more

Written for the Fall 2016 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

DVD Awards 2016, Il Cinema Ritrovato

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli, Alexander Horwath, Lucien Logette, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. (Although Mark McElhatten wasn’t able to attend the festival this year, he has continued to function as a very active member of the jury.)

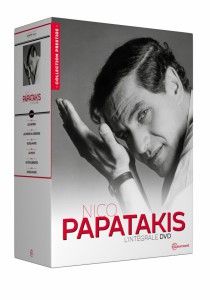

BEST SPECIAL FEATURES

Coffret Nico Papatakis (France, 1963-92) (Gaumont Vidéo, DVD). A comprehensive and cogent presentation of a neglected filmmaker from Ethiopia and a singular cultural figure in postwar France who ran an existentialist cabaret, produced major films by Jean Genet and John Cassavetes, gave the German singer Nico her name, and made many striking films over four decades. (JR)

BEST DVD SERIES

Coffret Collection 120 ans n.1 1885-1929 (France, 1885-1929) (Gaumont Vidéo, DVD). To celebrate its 120 years of activity in the film industry, Gaumont has published a series of nine beautiful box sets that summarize the whole history of cinema. Divided by decades, the box sets consist of 20 to 35 DVDs with the most representative films marked with a daisy symbol. The editions include films made by Alice Guy, Louis Feuillade, Dreville, Duvivier, Gabin, Louis de Funès, Pialat, and Deville, but also masterpieces by Losey, Fellini or Bergman that the French company co-produced. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 23, 1988). — J.R.

TORCH SONG TRILOGY

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Paul Bogart

Written by Harvey Fierstein

With Harvey Fierstein, Anne Bancroft, Matthew Broderick, Brian Kerwin, Karen Young, Ken Page, and Eddie Castrodad.

TALK RADIO

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Oliver Stone

Written by Eric Bogosian and Stone

With Bogosian, Alec Baldwin, Ellen Greene, Leslie Hope, John C. McGinley, and John Pankow.

As different as they are, Torch Song Trilogy and Talk Radio, both movie adaptations of plays, have several striking things in common. Each was written by and stars the author of the original play — Harvey Fierstein and Eric Bogosian, respectively. Both deal with marginal aspects of American life that seldom find their way into the commercial mainstream, which makes them new and vital in ways that most other recent releases are not. Both are effectively (if not literally) one-man shows whose auteurs are more their Jewish writer-stars than their directors, and the impact of each is directly tied to the uncommon theatrical skills of these individuals. And perhaps most significantly, both are a good deal more professional, entertaining, intense, and compelling than any other new Hollywood releases around, even if their commercial fates are substantially more precarious than those of most of their competitors. Read more

Here is the first review I ever wrote of a Pynchon novel, published in my college newspaper and signed “Jon Rosenbaum”. In fact, although I never reviewed Slow Learner, Pynchon’s collection of early stories, I suppose it could be said that I’ve reviewed all his novels to date, because this brief review in the Bard Observer begins with a two-paragraph review of V.

I’ll also be posting, separately and in the near future, my review of Mason & Dixon, which originally appeared in In These Times. And my reviews of Gravity’s Rainbow (for the Village Voice) and of Vineland and Against the Day (both in the Chicago Reader) can be found elsewhere on this site.

One possible point of interest about this piece of juvenilia is my early comparison of Pynchon with Rivette in relation to what might be called the poetics of paranoia, a subject I would return to. For whatever it’s worth, the disappointment I’ve generally felt regarding Pynchon’s post-70s work is matched by the overall disappointment I’ve felt regarding Rivette’s post-70s work, and in both cases I’ve felt guilty about this, because the work I prefer tends to be less sane (and therefore less conventional and more avant-garde) than the work that follows it. Read more

Written for the 11th issue of the bilingual, online La Furia Umana (January-March 2012) to introduce a Joe Dante dossier. — J.R.

One of the problems inherent in using the term “cult” within a contemporary context relating to film, either as a noun or as an adjective, is that it refers to various social structures that no longer exist, at least not in the ways that they once did. When indiscriminate moviegoing (as opposed to going to see particular films) was a routine everyday activity, it was theoretically possible for cults to form around exceptional items — “sleepers,” as they were then called by film exhibitors — that were spontaneously adopted and anointed by audiences rather than generated by advertising. But once advertising started to anticipate and supersede such a selection process, the whole concept of the cult film became dubious at the same time it became more prominent, a marketing term rather than a self-generating social process.

Joe Dante deserves a special place in what I would call the post-cult cinema because he is one of the few commercial American directors I know who has refused to hire a personal publicist, and for tactical reasons — someone, in short, who chooses to be recognized at best only by initiates (that is, by fellow cultists or would-be cultists, his comrades-in-arms) rather than by the public at large. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 3, 1989). — J.R.

NEW YORK STORIES

*** (A must-see)

“Life Lessons”

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Richard Prince

With Nick Nolte, Rosanna Arquette, and Patrick O’Neal.

“Life Without Zoe”

Directed by Francis Coppola

Written by Francis Coppola and Sofia Coppola

With Heather McComb, Talia Shire, Giancarlo Giannini, Don Novello, and Selim Tlili.

“Oedipus Wrecks”

Directed and written by Woody Allen

With Woody Allen, Mae Questel, Mia Farrow, and Julie Kavner.

With the exception of the recent and disappointing Aria, there have been no films made of late that consist of thematically related sketches, compilations of episodes by one director or more. New York Stories may help make the form fashionable again. The arbitrariness of the standard running time of features, at least from an artistic standpoint, makes a good many movies needlessly padded and a few others shorter than they should be, while the difficulty in marketing shorts discourages most commercially established filmmakers from even attempting to work in the form. New York Stories came about because Woody Allen wanted to make a short and decided that incorporating it within an anthology would make it commercially feasible.

The usual argument made against sketch movies is that they’re invariably uneven — which is true enough but also rather beside the point. Read more

This review originally appeared in the July 14, 1997 issue of In These Times. — J.R.

Pynchon’s Tangle

Mason & Dixon

By Thomas Pynchon

Henry Holt

773 pp. $27.50

It’s always been one of the paradoxes of Thomas Pynchon’s fiction that he combines the encyclopedic researches of a polymath with the rude instincts of a populist. V., The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow, the stories in Slow Learner, Vineland, and now Mason & Dixon synthesize an awesome array of scientific and historical speculation while steadily sabotaging, with a compulsive anti-elitism, every effort to marshal this material into the stuff of high art. Fusing studied literary pastiche with collegiate humor and flip song lyrics, philosophical soul-searching with barroom brawls and locker-room asides, Pynchon’s intricate and unwieldy narratives tend to define and confound boundaries in the same gesture. So it stands to reason that this epic about American origins, focused on a couple of low-level line drawers (the 18th century executors of the Mason-Dixon Line), winds up favoring sprawl over progression, digression over linear advance.

It’s surely too soon to post final verdicts about a novel that reportedly was almost a quarter of a century in the making. Read more

The following article, which originally appeared in the April 20, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader, without any star rating, is the only time I can recall writing at length in the Reader about an American TV series. (An edited version of this piece appears in a 1995 collection edited by David Lavery for Wayne State University Press, Full of Secrets: Critical Approaches to Twin Peaks, under the title “Bad Ideas: The Art and Politics of Twin Peaks“.) From a vantage point of almost two decades later, I wouldn’t be as quick today to insist that David Lynch’s work is devoid of any social commentary. What he has to say about the Hollywood community alone, especially in Inland Empire (2006), shows that he’s no longer as detached as he was.

Another invaluable tool for re-evaluation is the recent and superbly appointed Blu-Ray box set devoted to Twin Peaks. Despite some misgivings about the show’s second season (see, for instance, Martha Nochimson’s demurrals in her 1997 The Passion of David Lynch about some of the ways the show “perverted” Lynch’s original designs and conceptions), I continue to find much of it very absorbing. The same is true, so far, about the so-far uneven third season, despite the brilliance of the third episode. Read more

From the January 25, 2007 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

INLAND EMPIRE ****

DIRECTED AND WRITTEN BY DAVID LYNCH WITH LAURA DERN, JUSTIN THEROUX, JEREMY IRONS, KAROLINA GRUSZKA, HARRY DEAN STANTON, AND GRACE ZABRISKIE

David Lynch’s first digital video, almost three hours long, resists synopsizing more than anything else he’s done. Some viewers have complained, understandably, that it’s incomprehensible, but it’s never boring, and the emotions Lynch is expressing are never in doubt. Asked many years ago about the origins of the nightmarish Eraserhead (1978), his first and best feature, he forthrightly replied, “Philadelphia.” If asked the same thing today about the no less nightmarish Inland Empire, he might say, “Hollywood.”

Many of my colleagues believe Lynch’s best early feature is Blue Velvet (1986), which I regard as a gripping but limited piece of designer porn. Like his more offensive Wild at Heart and his more charming TV series Twin Peaks (both 1990), Blue Velvet offers a vivid illustration of how a man can turn his most lurid puritanical obsessions into clout and big money — and get an audience to wallow in those obsessions without thinking about them very hard. It has little of the meditative integrity and private intensity of Eraserhead, but then little in his work before Inland Empire did. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 6, 1989). — J.R.

THE LITTLE THIEF ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Claude Miller

Written by Annie Miller, Claude Miller, and Luc Beraud

With Charlotte Gainsbourg, Didier Bezace, Simon de la Brosse, Raoul Billerey, and Chantal Banlier.

The French cinema has perhaps never been more desperately in the doldrums than now, and this slump is best represented by the trips down memory lane that seem to be a major preoccupation in current French movies. Never entailing research or reevaluation, these simplified, nostalgic foreshortenings of the past often pare away much of what makes that past interesting.

Claude Miller’s The Little Thief (La petite voleuse) is a case in point because it purports to be, at least in this country, the last work of the late Francois Truffaut. (I’m told that no such claims were made about the film when it opened in France, and can understand why; even French amnesia doesn’t ordinarily extend quite as far as our own.) The film was developed out of a long-nurtured Truffaut project that Truffaut considered filming at various points throughout his career; a 30- or 40-page treatment (accounts differ) he wrote with Claude de Givray served as Miller’s starting point, although by all accounts this story has been extensively reworked and embellished, and even given a new ending. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, November 1976, Vol. 43, No. 514. — J.R.

Ultima Donna, L’ (The Last Woman)

ltaly/France, l976

Director : Marco Ferreri

Cert—X. dist–Columbia.Warner. p.c—Flaminia Produzioni Cinema (Rome)/Les Productions Jacques Roitfeld (Paris). p—Edmondo Amati. p. managers–Maurizio Amiti, Roberto .Giussani. asst. d—Enrique Bergier, Bernard Grenet. sc–Marco Ferreri, Rafael Azcona, Dante Antelli. story–Marco Ferreri. collaboration on dial–Noël Simsolo. ph—Luciano Tovoli. col—Eastman Colour. ed–Enzo Meniconi. a.d—Michel de Broin. m—Philippe Sarde. m.d—Hubert Rostaing. cost—Gitt Magrini. sd. ed— Gina Pignier, sd. rec–Jean-Pierre Ruh. l.p—Gérard Depardieu (Gérard), Ornella Muti (Valérie), David Biggani (Pierrot), Michel Piccoli (Michel), Renato Salvatori’ (René), Giuliana Calandra (Benoîte), Zouzou (Gabrielle), Nathalie Baye (Girl in Shopping Mall), Soulange Skyden (Girl at Night-club), Carole Lepers (Anne-Marie), Daniela Silverio (Jane), Vittorio Ganfoni (Policeman with Dogs), Guerrino Totis. 9,799 ft. 109 mins. French dialogue; English subtitles.

French title—La Dernière Femme

Gérard, a young engineer whose wife, Gabrielle, has recently left him, meets Valérie, the attractive teacher at the factory nursery where he goes to collect his thirteen-month-old son Pierrot, and invites her home with him; she agrees, and is assured by her lover Michel thathe won’t interfere. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1989). — J.R.

Gabriel Axel’s Danish feature, the 1987 Oscar winner for best foreign film, is based on an Isak Dinesen tale. On the whole, the adaptation is faithful but some of the qualities of Dinesen’s language are lost in translation or through abridgment, and the politics have been needlessly simplified. The plot concerns a French servant in a strict Lutheran household in Denmark — Norway in the original — whose family has perished in the French Commune uprising. The acting is impeccable and the ambience suffused with delicate charm, but overall this doesn’t aim at anything higher than Masterpiece Theatre or a Merchant-Ivory film. Aside from the elaborate serving of the eponymous meal, which expands greatly on the original, few of the additions constitute improvements. With Stephane Audran, Jean-Philippe Lafont, Jarl Kulle, Bodil Kjer, and Birgitte Federspiel (Ordet). In Danish with subtitles. 102 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

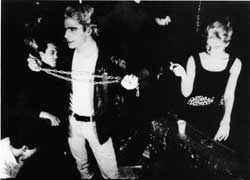

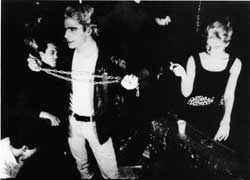

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1989). — J.R.

After paying $3,000 for the rights to Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange, Andy Warhol made this very loose adaptation (1965) using direct sound, with such Warhol regulars as Ondine and Edie Sedgwick, Gerard Malanga performing a whip dance, and music by the Velvet Underground. It’s one of Warhol’s very best — and most painterly — films, more interesting for what it does with crowded space than for the S and M. 64 min. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 12, 2005). — J.R.

Last Days

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Gus Van Sant

With Michael Pitt, Lukas Haas, Asia Argento, Scott Green, Nicole Vicius, Ricky Jay, and Thadeus A. Thomas.

A film about a junkie rock musician, played by Michael Pitt at his most narcissistic, doing nothing in particular for the better part of 97 minutes isn’t my idea of either a good time or a serious endeavor. Yet a few of my colleagues seem to be responding to Gus Van Sant’s Last Days the way some responded to The Passion of the Christ — taking it without a grain of salt or an ounce of irony. But it’s the grunge version of the Christ story, so that makes it hip.

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times writes that it’s about the “resurrection of Gus Van Sant,” the “mystery of human consciousness,” the “ecstasy of creation,” and “how sorrow sometimes goes hand in hand with the sublime.” Even a compulsive jokester like the New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane sounds like he just stepped out of Sunday school, writing, “Some of the motion has a hypnotizing grace,” and when the camera retreats from a house where Blake (Pitt) is noodling distractedly on his guitar, “We might as well be overhearing him at prayer.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 19, 1995). — J.R.

Mamma Roma

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Pier Paolo Pasolini

With Anna Magnani, Ettore Garofolo, Franco Citti, Silvana Corsini, Luisa Orioli, Paolo Volponi, Luciano Gonini, Vittorio La Paglia, and Piero Morgia.

Who can predict the changes in intellectual fashion over 20 years? In 1975, when the controversial Italian writer and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini was brutally murdered by a 17-year-old boy in a Roman suburb, he was no more in vogue than he had been throughout his stormy career. If any openly gay writer-director was an international star in the mid-70s, it was Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who at that point was spinning out as many as three or four features a year; he died in 1982 after an orgy of cocaine abuse.

Pasolini and Fassbinder were both maverick leftists who often alienated other leftists as well as everyone on the right, and both had a taste for rough trade, but in terms of their generations (Pasolini was born in 1922, Fassbinder in 1946) and cultural reference points they were radically different. The only reason to compare them now is to note how much their reputations and visibility have changed here over the last two decades. Read more