Written for a Portuguese exhibition catalogue in Fall 2016. My affectionate thanks to Nicole Brenez for both landing me this assignment and correcting a few of my imprecisions.– J.R.

1. On a film by Jean-Luc Godard

I’ll never forget the very strange sort of non-reception that appeared to greet the challenge of Jean-Luc Godard’s Numéro Deux when it first appeared in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The first time I saw the film, in the mid-1970s, soon after its unexpectedly wide commercial opening in Paris — a release apparently prompted by the misleading claim that it was a “remake” of A bout de souffle (premised on the fact that it had the same producer, Georges de Beauregard, as well as the same budget, without allowing for any inflation), plus the fact that it was being distributed by Gaumont — was at a large cinema just off the Avenue des Champs-Elysées, where I was startled to find myself the only person inside the auditorium. Communing all alone with that big screen containing many smaller screens was a singular experience in more ways than one.

When Numéro Deux was subsequently shown at the Edinburgh Film Festival, the key annual event of Marxist film theorists in the United Kingdom, many of the intellectuals associated with Screen magazine who had previously treated Le gai savoir and Vent d’est as exemplary manifestos for a political “counter-cinema”, quoting from its various speeches as if they were all graspable and teachable recipes for a revolutionary practice, abruptly dismissed Numéro Deux for its alleged “sexism” and “mystifications” (if they bothered to discuss it at all). Read more

Written in late November 2013 for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

En movimiento: The Season of Critical Inflation

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Am I turning into a 70-year-old grouch? Writing during the last weeks of 2013 — specifically a period of receiving screeners in the mail and rushing off to various catch-up screenings, a time when most of the ten-best lists are being compiled — I repeatedly have the sensation that many of my most sophisticated colleagues are inflating the value of several recent releases. And my problem isn’t coming up with ten films that I support but trying to figure out why so many of the high-profile favorites of others seem so overrated to me. All of these films have their virtues, but I still doubt that they can survive many of the exaggerated claims being made on their behalf.

Such as:

Gravity, hailed by both David Bordwell and J. Hoberman as a rare and groundbreaking fusion of Hollywood and experimental filmmaking, and not merely an extremely well-tooled amusement-park ride, is now being touted as a natural descendent of both Michael Snow’s La région central as well as 2001: A Space Odyssey, as if its metaphysical and philosophical dimensions were somehow comparable. Read more

Read more

Probably Alex Cox’s most underrated movie. From the Chicago Reader (December 4, 1987). — J.R.

WALKER

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Alex Cox

Written by Rudy Wurlitzer

With Ed Harris, Richard Masur, Rene Auberjonois, Marlee Matlin, Peter Boyle, Blanca Guerra, and Miguel Sandoval.

What is it about the American mind that insists on regarding itself as apolitical? It would be easier to understand such an attitude in a country with less political freedom than this one; here it seems willfully self-denying, like ordering a hamburger in a Chinese restaurant. From a Marxist and existential standpoint, being “apolitical” means accepting, hence supporting, the status quo — a political position like any other, acknowledged or not. Yet there is something in the national consciousness that resists such acknowledgment.

Reagan’s appeal has always rested in part on this form of self-deception, which can be traced back to most of his movie roles — the assumption that anyone as bland and as familiar as a favorite uncle can’t be sullied by anything as dirty as politics or ideology. The belated discovery that Reagan’s “apoliticism,” so closely linked with his triumph as Pure Image, chiefly consists of his capacity to do nothing at all, hasn’t eliminated the desire to fill the void with another static, charismatic presence — another movie, in short, to tide us over the many crises to come. Read more

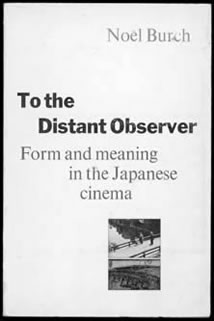

From American Film (July-August 1979). Incidentally, Criterion’s recent Blu-Ray of Ugetsu is ravishing, regardless of what Burch says (or, rather, doesn’t say).– J.R.

To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema by Noël Burch. Revised and edited by Annette Michelson. University of California Press, $19.50.

The most ambitious and detailed study of Japanese cinema since Joseph L. Anderson and Donald Richie’s pioneering history appeared twenty years ago, Noël Burch’s To the Distant Observer adopts an overall approach that is radically different from that of its predecessor. Modernist and materialist in orientation where other critics have been realist and transcendental, Burch argues for a nearly total revision of the way we perceive Japanese film — proposing a new set of criteria as well as an alternate canon of masterpieces.

To call his book controversial would almost be an understatement. Copies of a draft were circulated among a few film scholars in London more than four years ago, sparking a heated debate that has raged ever since. For Burch is arguing that “the most fruitful, original period” the Japanese film history coincided with the years between 1934 and 1943, when the Japanese people embraced “a national ideology akin to European fascism”. Read more

From American Film (October 1979). -– J.R.

The actors playing Chuckie and Mikey, a sinister vaudeville team dressed in matching tuxedos, top hats, and capes, are pretending to walk toward the camera. They move their feet without advancing anywhere. Behind them, a gigantic black-and-white blowup of a garden at Versailles, mounted on a platform, is slowly rolled away to further the partial illusion. Then they turn around and pretend to walk away from the camera, and the Versailles backdrop is slowly wheeled toward them. All this time the characters discuss a woman they have killed in Budapest.

“Think of it, ” Mikey says wistfully in a Russian accent. “I could have married a princess. ”

“All bourgeois dreams end the same way,’’ Chuckie replies in a disdainful tone. ”Marry royalty and escape.”

“OK, cut!” says Mark Rappaport, concluding the fifth and final take.

It’s the first day of shooting on Impostors, a macabre comedy by the Brooklyn-born independent filmmaker. The movie, Rappaport’s fifth feature, is being shot in his loft in the SoHo section of Manhattan, and spirits are running high. A young crew of about twenty persons — fifteen of them on the regular payroll — are clustered on one side of the loft. Read more

1. Taking a British Airways morning flight from Edinburgh to London this morning, I was delighted to discover that a tourist-class seat entitles me to a full hot British/Scottish breakfast — omelet, sausages, ham, mushrooms, and potatoes, with coffee served in an old-fashioned ceramic cup, at no extra charge. Simply imagining such a thing on any domestic flight in the U.S. nowadays would be indulging in a decadent form of nostalgia.

2. The intelligence, wit, and sharp writing one almost takes for granted in portions of the weekly press here. After bemoaning the phony “knowing” tone of David Thomson pretending to be authoritative about Orson Welles’ life at the time of his death in my last Notes entry, it’s worth quoting from three pieces that I happened to read during my 90-minute flight, all displaying good thoughts as well as good prose. The fact that I happened to just see Fantastic Mr. Fox two nights ago, in the Scottish coastal village St. Andrews, made the latter two pieces, both reviews of the film, especially interesting:

a. From “Your Call is Not Important To Us” by Will Self (New Statesman, 26 October) on mobile phones: “As defined by the psychiatric profession, psychosis is a blanket term for inadequate reality-testing (an ugly coinage, but you know what I mean). Read more

My column for Caíman Cuadernos de Cine, submitted on March 21, 2019. — J.R.

It’s tiresome to keep hearing from several American colleagues what a lousy year 2018 supposedly was for movies — “movies” being virtually equated with Hollywood crap in much the same way that “the world” is often equated with the U.S. (with Cuarón, Farhadi, Pawlikowski, and a few others occasionally accorded the dubious status of honorary Americans, usually on the basis of their Oscars). Given how much non-American cinema one can see nowadays via streaming, this is an inexcusable way of allowing the big companies to keep their stranglehold on what passes for film culture, making it easier than ever to miss out on what matters.

Even so, I’m embarrassed to admit that I didn’t recognize the brilliance of Christian Petzold until recently, when I saw Transit (2018) — having previously seen only his Ghosts (2005) and Barbara (2012). Having now accessed, in swift succession, his Phoenix (2014), Yella (2007), Jerichow(2008), and Barbara again — I feel that it’s the dreamlike, hallucinatory surfaces (both aural and visual) of Yella, Phoenix, and Transit more than the literal places and spaces of Jerichow and Barbara that best capture Pertzold’s investigations into historical and existential identity. Read more

This originally appeared in the January 10, 2001 issue of the Chicago Reader. It seems worth reprinting as a kind of adjunct to my overview piece about Oshima, written for Artforum in 2008 and also available on this site. –J.R.

Taboo

****

Directed and written by Nagisa Oshima

With Beat Takeshi (Takeshi Kitano), Ryuhei Matsuda, Shinji Takeda, Tadanobu Asano, and Yoichi Sai.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Mark your calendars. Over the next six weeks, the Music Box is offering three eye-popping masterpieces from Asia. This is a welcome sign–-as is the popularity of the breezy Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon in the multiplexes–-that American theaters and audiences are finally recognizing that a lot of the best movies come from the other side of the planet and that there’s as much diversity among them as there is among ours.

Yi Yi, which opens March 2, is a three-hour feature set in contemporary Taiwan. It was just voted best picture of the year by the National Society of Film Critics, the first foreign-language picture to receive this honor since Akira Kurosawa’s Ran 15 years ago. Its writer-director, Edward Yang, is one of the two or three undisputed masters of Taiwanese cinema, and the Film Center gave us a full retrospective of his work in 1997. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 8, 1993). — J.R.

A few years ago, world cinema received a shot in the arm from so-called glasnost movies from the former Soviet Union — pictures that had been shelved due to various forms of censorship, mostly political, and were finally seeing the light of day thanks to the relaxation or near dissolution of state pressures. The thought of an American glasnost may seem a little farfetched. But if we start to look at the awesome control exerted by multinational corporations over what we see, particularly in mainstream movies, the definition of what is and isn’t permissible — or, in business terms, what is “viable,” which in this country often comes to the same thing — may seem comparably restricted.

The best movies of 1992 weren’t exactly censored; but given the profound lack of media attention they received they would have achieved much more reality in most people’s minds if they had been. And nothing short of an American-style glasnost would give these films the cultural centrality they deserve. Only three of them received extended theatrical runs in Chicago, and perhaps only one or two got so much as a mention on Entertainment Tonight or in Time, Newsweek, or Entertainment Weekly. Read more

I am reprinting the entirety of my first and most ambitious book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, New York: Harper & Row, 1980) in its second edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) on this site in eleven installments. This is the tenth.

Note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

5—

Made in Hoboken

Douglas, Wyoming, 1914—three states away from where our old friend Gordon MacRae is still only a radical freshman or a freethinking sophomore at the University of Indiana—Bo is operating his very first movie theater, at the age of twenty-seven. Think of it: when Jonathan’s the same age, in 1970, he’s working fitfully on his second yet-to-be unpublished novel, completing his first yet-to-be unpublished book as an editor (a collection of film criticism he was commissioned to do), still living on the dregs of Bo’s inheritance, and dividing the first three months of the year among three countries: pursuing a heavy love affair in New York, having his appendix removed in London (and smoking hash with his brother Michael’s friends in a room called the Box), and taking acid all alone one beautiful spring afternoon in Paris, where he moved last fall, acid that suddenly prompts him to buy red paint, a roller, and brushes, and to go to work on his bedroom closets—a conversation with the wood, red saying one thing, grain saying another—and later sends him out the door and up rue Mazarine to the Odéon métro stop, a little after 6:30, to take the Porte de Clignancourt train as far as Châtelet and then the Mairie des Lilas train to République. Read more

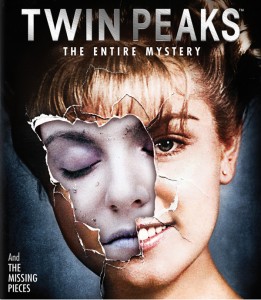

My column for the April 2015 issue of Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. Although I didn’t have the space to discuss this, it seems to me in retrospect that Jack Nance, even as a relatively minor character (Pete Martell), is as much the realistic backbone of Twin Peaks as he is the realistic anchor of Eraserhead — and, as such, he stands at the opposite end of the spectrum from such supernatural pasteboard characters as Bob (Frank Silva) and Windom Earle (Kenneth Welsh). — J.R.

The news that David Lynch and Mark Frost are preparing nine new Twin Peaks episodes — all to be directed by Lynch and set in the present, and to air on cable TV’s Showtime in 2016 — has coincided with the release of a beautifully designed Blu-Ray box set with ten discs, Twin Peaks: The Entire Mystery and The Missing Pieces, devoted to the 29 episodes broadcast in 1990 and 1991 and the subsequent prequel theatrical feature, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), and many extras. All this has prompted a re-evaluation of the series as a whole, which I’ve now seen in its entirety for the first time. A few critics have aided me in this quest—especially Michel Chion in his 1992 French book on Lynch, Martha P. Read more

This synopsis and review appeared in the December 1975 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin.

I’ve only just begun to familiarize myself with Moana with sound (see first still below), put together by the Flahertys’ daughter Monica, restored by Bruce Posner and Sami van Ingen (the Flaherty’s great-grandson), and posthumously released on Blu-Ray today by Kino Lorber. But I’ve already sampled enough of it — as well as all of Posner’s “short” (39-minute) history of the project, included along with other extras on the Blu-Ray — to view it as a major achievement, hopefully leading to a major reassessment of what I regard in some ways as Flaherty’s most neglected masterpiece. — J.R.

Moana

U.S.A., 1925

Directors: Robert J. Flaherty, Frances Hubbard Flaherty

Savai’i, a Samoan island. Near the village of Safune, Moana pulls taro root from the ground and peels it while his betrothed Fa’angase bundles leaves, his mother Tu’ungaita carries mulberry sticks and his younger brother Pe’a helps them. Setting off for the village, they set a trap for wild boar, the forest’s only dangerous animal, which they subsequently capture. Moana, Fa’angase, and Pe’a go spear-fishing, along with Moana’s older brother Leupenga. Back in the village, Tu’ungaita makes back-cloth for a lavalava, a native dress. Read more

I no longer recall who snapped this deliberately lopsided photo of Oliver Baumgarten (left), Alexis Tioseco (right), and me in spring 2007, when the three of us were the entire FIPRESCI jury at the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival. Our prize that year went to an eye-popping masterpiece, Amit Dutta’s Kramasha (To Be Continued…), from India — which later became one of the five late (2007) entries to my list of all-time favorite films in the Afterword of the second edition of my collection Essential Cinema — and discovering that great film with Alexis was for me the absolute high point of the festival.

As some of you have heard by now, Alexis, who was 28, and his Slovenian partner Nika Bohinc, who was almost 30 and another very talented film critic, were murdered yesterday in their home in Quezon City, the Philippines, apparently by burglars. Nika, whom I also knew, but less well, had only recently moved there from Ljubljana, Slovenia; Gabe Klinger has just posted a very tender and affectionate piece about both of them a few hours ago. And for the moment, at least, one can still access Alexis’ excellent web site, Criticine. (Postscript, 9/3/09: Adrian Martin writes from Melbourne that Nika’s own Ekran blog, also [mostly] in English, which I haven’t encountered until now, “with many fine pieces, is still also accessible”.) Read more

This was published at the end of my first year at the Reader, in their Christmas issue. –J.R.

BROADCAST NEWS *** (A must-see)

Directed and written by James L. Brooks

With Holly Hunter, Albert Brooks, William Hurt, Robert Prosky, Lois Chiles, Joan Cusack, and Jack Nicholson.

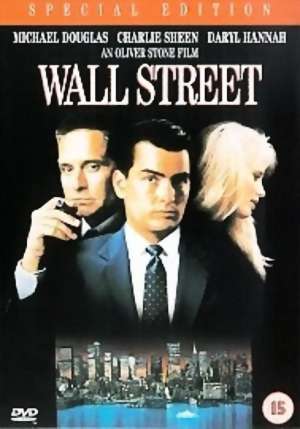

WALL STREET ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Oliver Stone

Written by Stone and Stanley Weiser

With Charlie Sheen, Michael Douglas, Martin Sheen, Daryl Hannah, Terence Stamp, Hal Holbrook, and Sylvia Miles.

Both Broadcast News and Wall Street score as punchy, energetic movies that are designed to feel as contemporary as possible without taking place in the literal present, and both pivot around a moral reckoning that accompanies economic cutbacks -– as if to remind us that this country’s Reagan-inspired spending spree, which tripled our trillion-dollar national debt, seems to be drawing to a fearful close. Apart from offering behind-the-scenes glimpses of their all-encompassing, hothouse professional turfs, both movies are built around the mise en scene of a moral crisis that splits the major characters apart –- each one charting a mutual seduction that leads to recriminations and the characters isolated in opposing moral camps. Yet the undisputed effectiveness of these films as entertainment seems at least partially predicated on fudging or at least mystifying the moral issues that they are bold enough to raise. Read more