I’ve taken this text and these photographs from The Point‘s web site, correcting the grammar of their transcript in a couple of places to clarify my meanings. — J.R.

The following is an edited transcript of remarks delivered by Jonathan Rosenbaum at High Concept Laboratories in Chicago on June 5, 2014. Mr. Rosenbaum and the other two panelists were asked to respond to The Point’s issue 8 editorial on the new humanities.

I’m the odd person out in this gathering because I’m not an academic, although I teach periodically in various, most often relatively unacademic, situations. And plus, I could be described as a failed academic. Before I came to Chicago I was teaching for four years at the University of California, Santa Barbara, but prior to that I actually began my failed academic career in the U.S. where Robert Pippin had his background, at UC San Diego. And in between I was an adjunct at NYU and at the School of Visual Arts, etc.

My academic background, actually, was in English. I was an English major as an undergraduate and in graduate school I did everything but a dissertation in English and American literature. But then I went to Europe and ended up being a journalist.

Read more

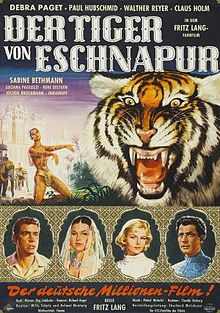

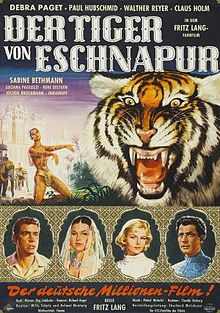

On January 3, 1978, during what must have been my first visit back to London after moving from there to San Diego in early 1977, I attended a private screening at the British Film Institute of glorious new prints of Fritz Lang’s Indian films. Over four years later, when I was invited to program “Buried Treasures” at the Toronto Festival of Festivals, I was delighted to be able to book these prints and thus hold what I believe was the North American premiere of Fritz Lang’s penultimate films in their correct versions, uncut and subtitled in English rather than dubbed. Luckily, Film Forum’s Karen Cooper attended this screening, and two years later, when she booked these prints for a theatrical run, she commissioned me to write program notes, reprinted below. — J.R.  THE TIGER OF ESCHNAPUR/THE INDIAN TOMB

THE TIGER OF ESCHNAPUR/THE INDIAN TOMB  (1958, 1959/101, 97 min.) Directed by Fritz Lang. Exec. Producer: Arthur Brauner. Screenplay by Lang & Werner Jorg Luddecke from a novel by Thea von Harbou & a scenario by Lang & von Harbou. Photographed by Richard Angst. Art direction by Helmut Nentwig, Willy Schatz. With: Debra Paget (Seetha), Paul Hubschmid (Harald Berger), Walter Reyer (Chandra), Claus Holm (Dr. Rhode), Sabine Bethmann (Irene Rhode), René Deltman (Ramigani). Read more

(1958, 1959/101, 97 min.) Directed by Fritz Lang. Exec. Producer: Arthur Brauner. Screenplay by Lang & Werner Jorg Luddecke from a novel by Thea von Harbou & a scenario by Lang & von Harbou. Photographed by Richard Angst. Art direction by Helmut Nentwig, Willy Schatz. With: Debra Paget (Seetha), Paul Hubschmid (Harald Berger), Walter Reyer (Chandra), Claus Holm (Dr. Rhode), Sabine Bethmann (Irene Rhode), René Deltman (Ramigani). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 16, 1996). — J.R.

My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud

Directed by Gerard Mordillat

Written by Mordillat and Jerome Prieur

With Sami Frey, Marc Barbe, Julie Jezequel, Valerie Jeannet, and Charlotte Valandrey.

Gerard Mordillat’s 1993 French feature My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud, showing this week at the Music Box, can be regarded only nominally as a biopic. Adapted from the diary of an obscure poet, En compagnie d’Antonin Artaud (which is also the film’s original, superior title), it tells the story of the poet’s relationship with Artaud over a two-year period, from May 1946 to March 1948, when Artaud died at the age of 52. In 1946 Artaud had just returned to Paris after nine years in an insane asylum, and Jacques Prevel befriended him and procured drugs for him, mainly laudanum, opium, and chloral. But the film has relatively little to say about Artaud’s work, except in passing, and virtually nothing about Prevel’s writing apart from his diary. Shot in beautiful, crisp high-contrast black and white, the movie certainly has something to do with the “life and times” of this bohemian duo — and Sami Frey and Marc Barbe do creditable jobs as Artaud and Prevel. Read more

Gerard Mordillat’s 1993 French feature My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud, showing this week at the Music Box, can be regarded only nominally as a biopic. Adapted from the diary of an obscure poet, En compagnie d’Antonin Artaud (which is also the film’s original, superior title), it tells the story of the poet’s relationship with Artaud over a two-year period, from May 1946 to March 1948, when Artaud died at the age of 52. In 1946 Artaud had just returned to Paris after nine years in an insane asylum, and Jacques Prevel befriended him and procured drugs for him, mainly laudanum, opium, and chloral. But the film has relatively little to say about Artaud’s work, except in passing, and virtually nothing about Prevel’s writing apart from his diary. Shot in beautiful, crisp high-contrast black and white, the movie certainly has something to do with the “life and times” of this bohemian duo — and Sami Frey and Marc Barbe do creditable jobs as Artaud and Prevel. Read more

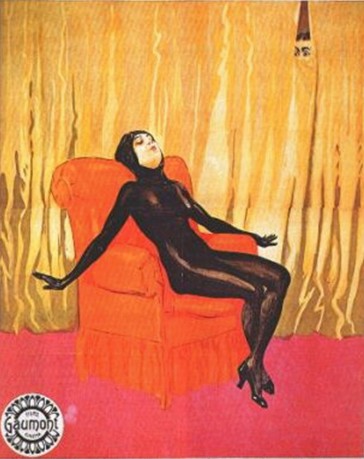

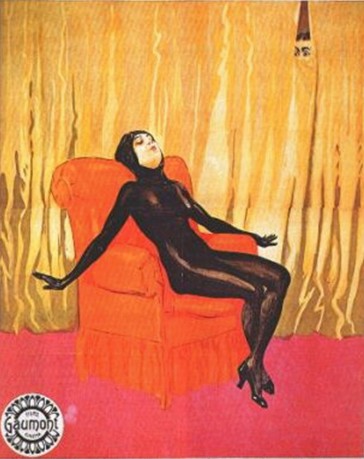

This article appeared in the October 9, 1987 issue of the Chicago Reader, and one good reason for reviving it now is to point up how out of date some of its remarks about Feuillade’s invisibility have become almost 34 years later. Back then, I noted, there was only one book about Feuillade; today I have seven more (all in French) of diverse sizes and scopes, and I’m sure my collection is far from exhaustive. Two full serials, Les vampires (1915) and Judex (1916), are available in the U.S., as is an excellent restoration of the multichaptered Fantômas (1913-1914) on Blu-Ray, so I’m still hoping that Tih Minh (1918), still my favorite, not to mention Barrabas (1919) and even La nouvelle mission de Judex — a 1917 crime serial I’ve never seen which is reputed to be inferior to the others — will also surface eventually. (2021 postscript: I’m about to order Tih Minh from French Amazon.) Also, Kino International has released Gaumont Treasures1897-1913, with one of its three discs devoted to Feuillade short films made between 1907 and 1913, as well as a documentary “featurette” about him. — J.R.

LES VAMPIRES

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Louis Feuillade

With Musidora, Édouard Mathé, Marcel Lévesque, Jean Aymé, Delphine Renot, Stacia Napierkowska, Fernand Hermann, Renée Carl, Louis Leubas, Louise Lagrange, Moriss, and Bout de Zan. Read more

My Fall 2018 column for Cinema Scope. — J.R.

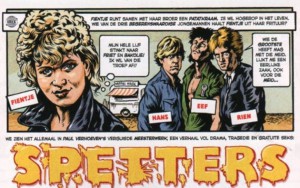

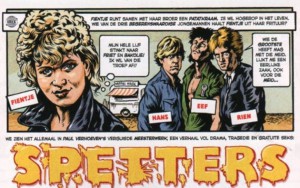

Paul Verhoeven gives exceptionally good audio commentary, especially on the Kino Lorber Blu-ray of Spetters (1980), a powerful feature about teenage motocross racers in a small Dutch town that I’ve just seen for the first time. Speaking in English, Verhoeven tells us a good deal about Dutch culture and life at the time his film was made; his own ideological motivations (such as his desire to depict accurately the behaviour of his young working-class characters) and personal contributions to the script (especially, but not exclusively, those relating to his early involvement with Pentecostal Christianity); his literary influences (in particular, the role played by Céline in conceptualizing the final sequence) and his strategies as a director (including the use of his own dog, who also turns up in The Fourth Man [1983]); his relations with his producer, his locations in and around Rotterdam, his cast and how he directed them; the differences between shooting in Holland and shooting in the US; the filming of stunts; his tricky dealings with Dutch government representatives to avoid censorship (which involved lying and subterfuge); the film’s disastrous initial critical reception, which had a lot to do with Verhoeven subsequently moving to Hollywood; and a great deal more. Read more

I believe that this essay was completed in spring 2010 — for a rather formidable book about Austrian experimental film edited by Peter Tscherkassky, Film Unframed: A History of Austrian Avant-Garde Cinema, available here and here and here. — J.R.

1

The lessons available from Lisl Ponger’s cinema take many forms, but perhaps one could claim that most of them are separate versions of the same lesson — the lesson of coming to terms with our own ignorance. This is already apparent in the most elementary way in the earliest film of hers I’ve seen, Film — An Exercise in Illusion 1 (1980), a travelogue in which any precise sense of what it is that’s traveling — the camera? the camera’s aperture? the scenery? — becomes ambiguous. More specifically, if the essence of film in general and film illusion in particular is motion, these three minutes of silent, super-8 shots of Venice, filmed from a moving boat — or maybe it’s one shot and/or several moving boats — features movement within the camera as well as outside it, through extreme changes in light. Which is another way of saying that we don’t really know what we’re watching, even if it’s the nature of film illusion to persuade us that we think we know, conning us into superimposing some touristic narrative over whatever we’re seeing. Read more

From the January 7, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

To preserve and present the best world cinema, France has the Cinematheque Francaise and England has the British Film Institute; we’ve got the American Film Institute, which doesn’t even have a clue about the best Hollywood movies. Consequently most younger American viewers have never seen a film by Alain Resnais, probably the greatest living French filmmaker, who’s never made an indifferent or unadventurous film and who’s much more talented and innovative than Francois Truffaut. From Resnais’ first three features, all masterpieces — Hiroshima, mon amour (1959), Last Year at Marienbad (1961), Muriel (1963) — to dazzling later works — Stavisky (1974), Providence (1977), Mon oncle d’Amerique (1980), Melo (1986) — he’s remained a master. On connait la chanson (1997), a more accurate translation of which might be “I Recognize the Tune,” was inspired by British screenwriter Dennis Potter (Pennies From Heaven); its characters frequently break into lip-synched French pop songs, which serve as cross-references to their moods and aren’t always bound by gender. (When Resnais made similar use of French film clips in Mon oncle d’Amerique, contemporary actress Nicole Garcia was cross-referenced with Cocteau’s actor Jean Marais.) A comedy about real estate and class differences, Same Old Song was the biggest hit of Resnais’ career in France at that point; it’s less popular among viewers unfamiliar with the music, but even if you can’t follow all the nuances, this is fun and different and at times mysterious (periodically revealing Resnais’ Surrealist roots), and it superbly captures Paris in the 90s. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 25, 2007). — J.R.

OUT 1 ****

DIRECTED BY JACQUES RIVETTE | WRITTEN BY RIVETTE AND SUZANNE SCHIFFMAN WITH PIERRE BAILLOT, JULIET BERTO, MICHEL DELAHAYE, JACQUES DONIOL-VALCROZE, FRANCOISE FABIAN, HERMINE KARAGHEUZ, BERNADETTE LAFONT, MICHELE MORETTI, AND ERIC ROHMER

WHEN Sat 5/26, 2:30 PM (episodes 1 and 2) and 7 PM (episodes 3 and 4); Sun 5/27, 2:30 PM (episodes 5 and 6) and 6:45 PM (episodes seven and eight)

WHERE Gene Siskel Film Center, 164 N. State

PRICE $30

INFO 312-846-2600

MORE Box meals from Whole Foods will be available during dinner breaks for $10, but must be ordered by Thu 5/24.

***

QUESTION: Why did you choose the title Out?

RIVETTE: Because we didn’t succeed in finding a title. It’s without meaning. It’s only a label. — from a 1974 interview

Jacques Rivette has made several good films and four great ones, consecutively: L’Amour Fou (four hours, 1968), Out 1 (12 hours, 1971), Out 1: Spectre (four hours, 1972), and Celine and Julie Go Boating (three hours, 1974). It’s not their epic length that sets these apart from the rest of his filmography — there are others by Rivette that are plenty long — but their improvisatory nature. Read more

Written for the 120th and final issue of Trafic, Fall 2021, where it appears in Jean-Luc Megus’ French translation. Contributors to this special issue were invited to write about something treasured, bearing in mind the quote from Ezra Pound that’s cited. — J.R.

“I never know how I should end my solos,” John Coltrane reportedly once said to Miles Davis, to which his boss gruffly replied: “Try taking your horn out of your mouth.”

Coltrane’s conceptual orientation versus Davis’s blunt practicality can be felt in the former’s symmetrical, multi-note flurries and rude honks up and down scales, furiously covering almost every available silence with his “sheets of sound”, and the latter’s jagged, elliptical smears and little-boy cries separated by sudden pauses that often register like either interruptions or abrupt afterthoughts, second-guessing himself.

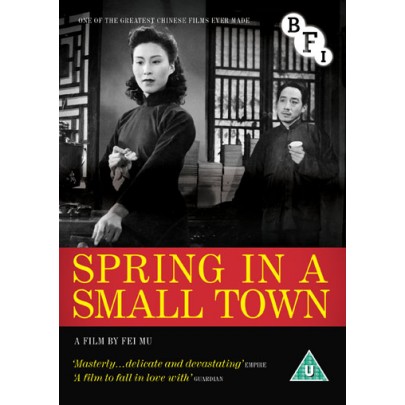

An almost sexual alternation of giving and withholding in a jazz solo becomes a tug of war between conflicting formal as well as sexual impulses — Davis’s version of coitus interruptus versus Coltrane’s giddy flirtations and unresolved foreplay. It persists throughout director Fei Mu’s and screenwriter Li Tianji’s extraordinary Spring in a Small Town (1948), a troubled and troubling piece of cinematic chamber music that seems all the more passionate yet intensely bottled up during the romantic and sexual frustrations of the Coronavirus pandemic. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 10, 1993). — J.R.

THE PIANO

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Jane Campion

With Holly Hunter, Harvey Keitel, Sam Neill, Anna Paquin, Kerry Walker, Genevieve Lemon, Tungia Baker, and Ian Mune.

Given how sexy and volatile it is, it’s no surprise that The Piano is a hit. It’s also no surprise, given the strong-arm tactics of the distributor and the hype of some reviewers, that a certain critical backlash is already setting in, as evidenced by a lucid and considered dissent by Stuart Klawans in the Nation and a rather lazy dismissal by Stanley Kauffmann in the New Republic. People like myself who are passionate fans of Jane Campion’s previous work may be somewhat churlish that many other people are finding their way to her work only after it has become juiced up, simplified, and mainstreamed — like the people who bypassed the dreamy finesse of Eraserhead on their way to the relative crudeness of Blue Velvet. It’s certainly regrettable that viewers who weren’t interested in seeing Campion’s 1989 film Sweetie until after they saw The Piano now have to contend with a lousy video transfer that doesn’t begin to do justice to Campion’s colors and compositions. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 29, 1997). To tell the the truth, over 17 years later, I’m a little embarrassed about having given this movie four stars. For all my affection for James L. Brooks, in spite of everything (and including his most recent picture, the much-reviled How Do You Know), this is far from being his best work. — J.R.

As Good as It Gets **** Masterpiece

Directed by James L. Brooks

Written by Mark Andrus and Brooks

With Jack Nicholson, Helen Hunt, Greg Kinnear, Cuba Gooding Jr., Skeet Ulrich, Shirley Knight, Yeardley Smith, Lupe Ontiveros, Jesse James, and Jill.

As a TV illiterate who probably hasn’t watched a sitcom regularly since The Honeymooners, who’s never seen Taxi, Rhoda, Lou Grant, Room 222, or The Tracey Ullman Show, and caught only the final episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, I don’t know much about the world James L. Brooks sprang from as an artist. In fact, apart from several episodes of his two cartoon series, The Simpsons and The Critic, I don’t know his TV work at all. And as someone who regards movie test-marketing as one of the sleaziest, most destructive practices in Hollywood, I’m more than a little skeptical about a writer-director-producer who believes in it so religiously that after the previews of his previous feature, the musical I’ll Do Anything, he recut it so extensively he made it a nonmusical. Read more

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

I’ve been getting increasingly suspicious of ten-best lists–maybe because the studios have been treating them as increasingly important. I’ve always regarded such list making as a critical activity, a form of stocktaking that benefits critics and audiences alike. But it’s becoming obvious that studios value the lists only as a part of their ad campaigns, and they seem to arrange their multiple end-of-the-year screenings and mail out their numerous “screener” videos for the press accordingly. Why else are so many reviewers implausibly claiming that most of the best movies of 2000 came out during the last two weeks of the year or haven’t even surfaced yet? Are they suffering from amnesia? Or are they simply going for the bait?

The studios define the year according to when movies open in New York and Los Angeles, where they’re often first screened in November and December so that they qualify for that year’s Oscars. As a consequence, critics in what the studios see as the hinterlands, including Chicago, are being encouraged to put movies on their ten-best lists that their readers can’t see for some time.

If studios cared about the services performed by criticism–which range from providing background information and an overall context for new releases to launching discussions about their subjects and explaining why these movies matter–they’d try to let critics see films shortly before they have to review them. Read more

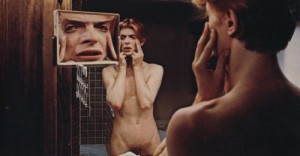

From Monthly Film Bulletin No. 507, April 1976. –- J.R.

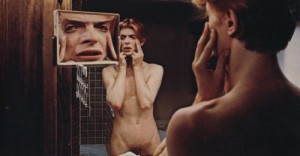

The Man Who Fell To Earth

Great Britain, 1976 Director: Nicolas Roeg

A stranger from another planet lands in New Mexico; calling himself Thomas Jerome Newton, he sells a series of rings to various jewellery stores and soon amasses a small fortune. He approaches Oliver Farnsworth, a homosexual lawyer in New York specializing in patents, shows him his plans for nine inventions destined to transform the communications industry, and concludes an agreement whereby Farnsworth supervises Newton’s World Enterprises Corporation and communicates with Newton, who wishes to maintain his privacy, chiefly by phone. Dr. Nathan Bryce, a chemical engineering professor, becomes intrigued by the corporation and decides to learn more about its master-mind. When Newton faints in an elevator, unaccustomed to the acceleration, the attendant, Mary-Lou, nurses him back to health and becomes his lover, tempting him into a taste for gin. After building a house on the lake where he landed and inaugurating a private space program, Newton hires Bryce as a consultant, and the latter discovers with a hidden X-ray camera that Newton s metabolism is not human. Newton intimates that he came to Earth because his race was dying from a lack of water and that his space program is designed to return him to his wife and children. Read more

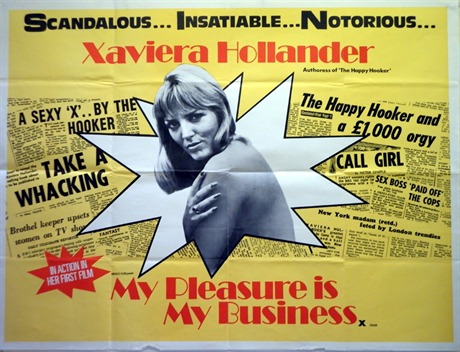

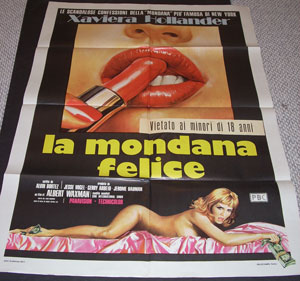

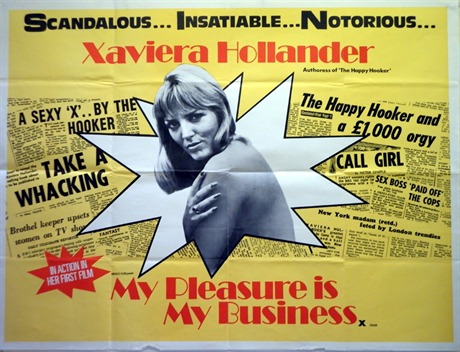

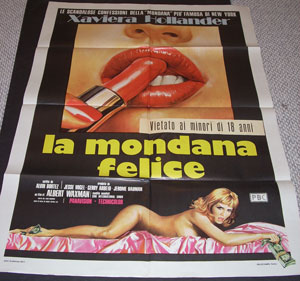

From Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 495). — J.R.

My Pleasure Is My Business

Canada, 1974 Director: Albert S. Waxman

Deported from America by a U.S. senator who wants to keep her

away from his son-in-law, Gabrielle, a promiscuous movie star and

sexual liberationist, is flown to the country of Gestalt. After

confering with his aides, the corrupt Prime Minister decides to admit her

into the country, thereby hoping to deflect some of the charges of

immorality laid against the government. Gabrielle is accorded a

luxurious suite by a North African hotel manager in exchange for

the promise of sexual favors, and applies for a job as sexual

therapist with pudgy psychiatrist Freda Schloss, who turns out to

want the therapy herself. While the Prime Minister and his

henchmen plot ways-of arresting her for prostitution,

Gabrielle picks up an artist in a cafe and makes love with

him in his flat, looks up an old French girlfriend who acts

in porn films (along with the local police chief), and attends

a wild costume party given by another old friend. Cornered

by the police when she returns to her hotel, Gabrielle

persuades them to drop the charges by reminding the

police chief of his skin-flick activity. Read more

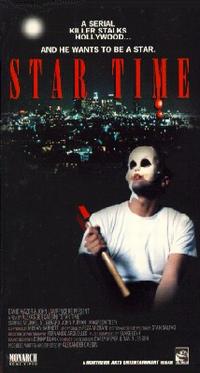

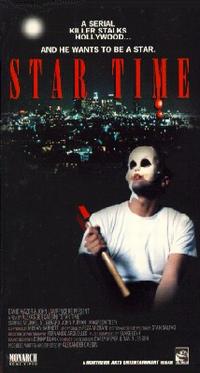

This appeared in the May 21, 1993 issue of the Chicago Reader. Although the YouTube link given below no longer works, I can happily report that it’s out now on DVD. — J.R.

STAR TIME

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Alexander Cassini

With Michael St. Gerard, John P. Ryan, Maureen Teefy, and Thomas Newman.

I doubt that any current media buzz term is more ideologically polluted than “family values.” Even its alternative, “suitable for the whole family,” doesn’t contain the same puritanical lies. The egregious false assumptions built into this phrase as it’s now used are breathtaking: that families are all alike when it comes to their values; that these shared values are somehow independent of — and therefore free of — the sex and violence purveyed by Hollywood movies (“sex and violence” invariably viewed as an irreducible entity that also mysteriously includes profanity); and that, because they eschew sex and violence, “family values” are uniformly good and healthy. These assumptions seem predicated on the notion that everything bad that happens in society necessarily occurs outside the home, on the streets. Never mind that statistics show that an inordinate amount of lethal violence occurs during national holidays, in homes, between family members; this is factored out of the discussion along with the inconvenient fact that babies (and therefore families) are generated by sex, not storks. Read more

Gerard Mordillat’s 1993 French feature My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud, showing this week at the Music Box, can be regarded only nominally as a biopic. Adapted from the diary of an obscure poet, En compagnie d’Antonin Artaud (which is also the film’s original, superior title), it tells the story of the poet’s relationship with Artaud over a two-year period, from May 1946 to March 1948, when Artaud died at the age of 52. In 1946 Artaud had just returned to Paris after nine years in an insane asylum, and Jacques Prevel befriended him and procured drugs for him, mainly laudanum, opium, and chloral. But the film has relatively little to say about Artaud’s work, except in passing, and virtually nothing about Prevel’s writing apart from his diary. Shot in beautiful, crisp high-contrast black and white, the movie certainly has something to do with the “life and times” of this bohemian duo — and Sami Frey and Marc Barbe do creditable jobs as Artaud and Prevel.

Gerard Mordillat’s 1993 French feature My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud, showing this week at the Music Box, can be regarded only nominally as a biopic. Adapted from the diary of an obscure poet, En compagnie d’Antonin Artaud (which is also the film’s original, superior title), it tells the story of the poet’s relationship with Artaud over a two-year period, from May 1946 to March 1948, when Artaud died at the age of 52. In 1946 Artaud had just returned to Paris after nine years in an insane asylum, and Jacques Prevel befriended him and procured drugs for him, mainly laudanum, opium, and chloral. But the film has relatively little to say about Artaud’s work, except in passing, and virtually nothing about Prevel’s writing apart from his diary. Shot in beautiful, crisp high-contrast black and white, the movie certainly has something to do with the “life and times” of this bohemian duo — and Sami Frey and Marc Barbe do creditable jobs as Artaud and Prevel.