This review originally appeared in the July 14, 1997 issue of In These Times. — J.R.

Pynchon’s Tangle

Mason & Dixon

By Thomas Pynchon

Henry Holt

773 pp. $27.50

It’s always been one of the paradoxes of Thomas Pynchon’s fiction that he combines the encyclopedic researches of a polymath with the rude instincts of a populist. V., The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow, the stories in Slow Learner, Vineland, and now Mason & Dixon synthesize an awesome array of scientific and historical speculation while steadily sabotaging, with a compulsive anti-elitism, every effort to marshal this material into the stuff of high art. Fusing studied literary pastiche with collegiate humor and flip song lyrics, philosophical soul-searching with barroom brawls and locker-room asides, Pynchon’s intricate and unwieldy narratives tend to define and confound boundaries in the same gesture. So it stands to reason that this epic about American origins, focused on a couple of low-level line drawers (the 18th century executors of the Mason-Dixon Line), winds up favoring sprawl over progression, digression over linear advance.

It’s surely too soon to post final verdicts about a novel that reportedly was almost a quarter of a century in the making. But the evidence after a first reading is that the same paradoxical, all-American anti- intellectualism that has often empowered Pynchon in the past to ride roughshod over decorum has finally caught up with him and become a kind of trap –- even a kind of escape-clause for his seriousness. Brilliant as it often is in both design and detail, Mason & Dixon afforded me less pleasure than any Pynchon novel to date, perhaps because the imagination that might have melded it all into a vision seems to be working at half the intensity such a farrago requires. The 18th century as a living entity never quite emerges, even if ideas and fancies about it abound. Scenes are mainly sketched in rather than painted: For example, when Mason and Dixon first meet, at a public execution in London, Pynchon never gets around to describing the execution itself.

Even Vineland, the most problematic of Pynchon’s novels before this one, is more emotionally affecting, registering a massive sense of personal loss that not even his artistry and intelligence can entirely rationalize or transform. Noting the 18th century setting of Mason & Dixon, Boston Phoenix review Peter Keough has shrewdly called the novel pre-revolutionary. In relation to 60s and early 70s counterculture, the subject of Vineland, it is plainly post-revolutionary as well. The sense of historical defeat enacted and wrestled with in Vineland is finally accepted here, and the cost of that acceptance is a crippling, willful desire to provide endless stretches of light entertainment — presumably administered like a narcotic in order to dull the pain. Maybe if I were lightly entertained I’d have less cause for complaint; too much of the time, I felt I was being hustled through the fun like a bout of basic training.

For all the preoccupations with history in Pynchon’s previous work, Mason & Dixon is his first historical novel — if only because the title protagonists, British surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, are historical figures whose lives can’t be invented out of whole cloth. But just because these men belong to history doesn’t mean that history or agency falls within their grasp. Basically fall guys, more acted upon than actors, they are defined in the novel mainly as behavioral essences. melancholy London astronomer Mason favors wine and perpetually mourns the death of his wife Rebekah. The taste of cheerful rural surveyor Dixon, the younger of the two, runs more to whisky and womanizing. Pynchon plays Mason’s brooding against Dixon’s laid-back carousing as the yin and yang of his own sensibility. Yet for all his attempts at balance, it’s the melancholy that predominates.

A little over halfway through the novel, the principal recounter of their adventures, the fictional Reverend Wicks Cherrycoke, offers a bit of theory on what comprises history. This quote from his monograph, “Christ and history,” might be taken as an apologia for Pynchon’s own narrative method: “History is not Chronology, for that is left to lawyers, — nor is it Remembrance, for Remembrance belongs to the People. History can as little pretend to the Veracity of the one, as claim the Power of the other, — her Practitioners, to survive, must soon learn the arts of the quidnunc, spy, and Taproom Wit, — that there may ever continue more than one life-line back into a Past we risk, each day, losing our forebears in forever, –not a Chain of single Links, for one broken Link could lose us All, –rather, a great disorderly Tangle of Lines, long and short, weak and strong, vanishing into the Mnemonick Deep, with only their Destination in common.”

***

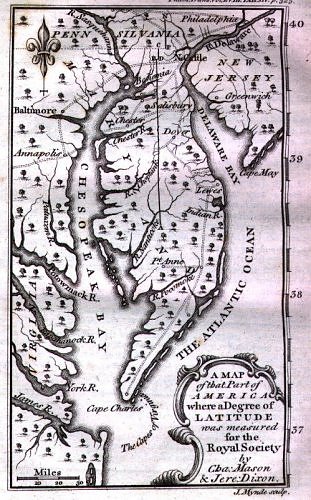

Mason and Dixon’s lives together, governed by the Royal Astrological Society, consist of (1) being dispatched in 1761 to the Cape of Good Hope to observe the transit of Venus (a rare alignment of the earth, sun, and Venus), after an earlier scheme to observe the transit from Sumatra was thwarted by the attack of a French frigate on their ship en route; (2) being sent to survey and establish the 233-mile line between Maryland and Pennsylvania (1765-1768) that became the dividing line in the Civil War a century later; and (3) being sent to Ireland in 1769 to observe the second transit of Venus and other astral phenomena.

Pynchon seizes upon this linear three-part itinerary to create his his overall narrative structure. He splits the novel into three sections like a sandwich (one of the 18th century inventions evoked along the way). America is the big lump of meat to be carved up between the bread slices of the two astronomical assignments. (The book’s title is another sandwich in which the ampersand, a curving tangle, is the filling between two matching linear masses of five letters each.) Parceled into 78 bite-size chapters, the story is relatively easy to read, once one becomes accustomed to the 18th century language. But the novel is almost impossible to digest as something much more than a miniseries.

Not counting a few side trips, flashbacks, and a framing device that takes in the deaths of the two heroes, Mason and Dixon’s three assignments make up the basic plot of the novel. As events, they aren’t terribly interesting in themselves, though as applications of knowledge, Pynchon sees them as virtually the sum of the aspirations of 18th century Enlightenment. The importance of the Mason-Dixon Line in separating the slave-owning South from the abolitionist North became clear only some time after the surveyors’ efforts. This doesn’t prevent both characters from participating in an ongoing debate about the political and philosophical implications of their work, which forms the novel’s most sustained through-line.

But the moment-to-moment texture of Mason & Dixon, especially its 458-page middle section, is far from linear. I’m speaking, of course, about the American wilderness that the Mason-Dixon line is supposed to be bisecting, regulating, and taming. Perceived mainly as disorderly interpolations, this great “Tangle of Lines” evoked by Cherrycoke comes in the form of tall tales, crackpot theorizing, and other digressions heard and encountered by Mason and Dixon during their four years of tedious (if enlightened) line-drawing. It’s only when the chaotic tangle of interpolations and the straight line of the surveyors are seen juxtaposed that the design of the novel starts to seem less mechanical and more mysterious.

Following a single hero, Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon’s 1973 novel, begins like a relatively conventional story only to wind up in a non-narrative freefall. The novel apes the arc of a rocket’s ascent and descent by surrendering to gravity while scattering its hero’s quest and identity. By contrast, Mason & Dixon interfaces linear, rational plot with a tabgle of surmise and deflection. The jumble of countless miniplots adds up to no story at all but a kind of obsessive doodling. Among the doodles are segments that a good many other reviewers have been showering with praise: a tale of a giant cheese, a running gag about a mechanical duck in love with a French chef, a dope-smoking session with George Washington in Mount Vernon, a talking dog, and countless others. Some of these indeed have their riotous, ingenious, or even moving bits, yet taken in bulk they often seem programmatic and forced — a determination to be lighthearted that weighs heavily on the project as a whole.

This tendency has always been somewhat operative in Pynchon’s work; perhaps what makes it more limiting here is the lesser amounts of passion and urgency that set it off. It’s almost as if Pynchon regards himself now as a journeyman like Mason rather than the explorer he used to be. He thinks he knows what’s out there in the wilderness, and, determined not to lose his bearings, he’s content to spin goofy, boys-club yarns about it. I wish him well, but I miss the fear and madness that pierced his earlier quests.

— In These Times, Vol. 21, No. 27, July 14, 1997