From the Chicago Reader (January 21, 2005). — J.R.

Rarely shown in the U.S. these days, this 1941 film of the wildly deconstructive stage farce with Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson is still regarded as a classic in Europe, and it lives up to its reputation. The credit sequence establishes the wartime mood with its vision of hell as a munitions factory (where demons preside over the packaging of Canned Guy and Canned Gal), which is shortly revealed as a movie soundstage, the first of many metafictional gags. Very belatedly the movie gets around to telling a spare musical-comedy story (with swell numbers by Martha Raye and the jazz duo of Slim Gaillard and “Slam” Stewart, and some very acrobatic jitterbugging), but the main bill of fare is manic nonsense that almost makes the Marx Brothers look sober. H.C. Potter directed; with Mischa Auer, Shemp Howard, and Elisha Cook Jr. 84 min. Sun 1/23, 7 PM, Univ. of Chicago Doc Films.

Read more

I am reprinting the entirety of my first and most ambitious book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, New York: Harper & Row, 1980) in its second edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) on this site in eleven installments. This is the eighth.

Note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

4—

Rocky Horror Playtime Vs. Shopping Mall Home

Seven weeks ago, when I received a call from Adriano Aprà in Rome inviting me to speak at this conference, I was in my hometown, Florence, Alabama, where my parents live today.[1] I have moved with all my belongings seventeen times in the past twenty years, and I will have to find and move to yet another place in New York as soon as I return from this conference. Nevertheless, I consider myself unusually fortunate, fortunate not only in being here—in this city and this country for the first time in my life—but in having a hometown to return to year after year: a fixed reference point. And fortunate in being the grandson of the man who ran most of the local movie theaters when I was growing up, which meant that I had virtually unlimited access to most of what was shown. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1990). Thanks to the interview with Casper Tybjerg on Criterion’s new dual-format release, I’m no longer sure if this was Dreyer’s “first substantial commercial release outside Scandinavia,” because Michael, made just before in Germany, also reportedly made a considerable splash. — J.R.

Formally and politically decades ahead of its time, Carl Dreyer’s wonderful silent Danish comedy (1925), his first substantial commercial success outside Scandinavia, recounts what happens when a working-class wife and mother, prompted by an elderly nurse, walks out on her tyrannical and demanding husband, who then has to fend for himself. Restricted mainly to interiors, Dreyer’s masterful mise en scene works wonders with the domestic space, and his script and dialogue make the most of his feminist theme. 110 min. (JR)

***

It’s all a matter of exquisite balance — between one shot and the next, between the first half of the film and the second half, between screen left and screen right.

Criterion’s dual-format edition of Carl Dreyer’s 1925 Master of the House scores as a modern film because Dreyer always knows how to modulate all his characters, and his actors’ beautiful performances, even when they’re at their most archetypal, whether in domestic tableaux or in climactic close-ups. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 19, 2006). — J.R.

The Lost City

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Andy Garcia

Written by G. Cabrera Infante

With Garcia, Steven Bauer, Richard Bradford, Nestor Carbonell, Lorena Feijoo, Bill Murray, Dustin Hoffman, Tomas Milan, and William Marquez

An intellectual initially associated with Castro’s revolution, G. Cabrera Infante (1929-2005) founded the Cuban Cinematheque and was known as both the Cuban James Joyce and the Cuban Laurence Sterne. He spent his final 39 years in voluntary exile in London, and his last screenplay was for The Lost City, the first feature directed by Andy Garcia. Among his works available in English are the novels Three Trapped Tigers, View of Dawn in the Tropics (the most succinct and measured, and my favorite), and Infante’s Inferno; his nonfiction includes Holy Smoke (a tribute to Havana cigars, his first book written in English) and A Twentieth Century Job, a collection of film criticism published under the pseudonym G. Cain (derived from his first initial and the first two letters of Cabrera and Infante). And there’s the screenplay for the 1971 Hollywood thriller Vanishing Point, also credited to Cain.

Sixteen years ago Garcia decided he wanted to adapt Cabrera Infante’s unadaptable, pun-packed, joyfully multicultural Three Trapped Tigers, an epic about Havana nightclub life during the late Batista period. Read more

Film In memoriam, Ingmar

In response to the recent death of Ingmar Bergman, the Chicago Cinema Forum has organized a Bergman marathon (Chicagoist termed it a “crash course in Bergman”) to be held at the Chopin Theatre this coming weekend. Included will be the local premiere (two screenings) of a recent three-part, three-hour documentary about Bergman made for Swedish TV and screenings of five major Bergman features: 16-millimeter prints of Sawdust and Tinsel (1953), The Seventh Seal (1957), Wild Strawberries (1957), and Persona (1966), and a DVD projection of the 188-minute version of Fanny and Alexander (1982), a Bergman miniseries that was the last thing he ever shot on film.

All five of the features will be introduced and discussed by local critics. I’ll be trying my hand at Sawdust and Tinsel, and the founder of Chicago Cinema Forum (and organizer of this event), Gabe Klinger, will do Fanny and Alexander; WBEZ producer Alison Cuddy will introduce The Seventh Seal, Time Out Chicago‘s Ben Kenigsberg will introduce Wild Strawberries, and National Louis University prof Robert Keser will introduce Persona. The social aspect of the Chicago Cinema Forum has been a central part of Klinger’s project from the beginning, and two hour-long receptions on Saturday and Sunday, offering a further chance to discuss Bergman, are also scheduled.

Read more

The following was put together for Jean-Luc Godard: Documents, a huge, large-format, 448-page (+ DVD) compendium put together by Nicole Brenez (in collaboration with Michael Witt) and published by the Centre Pompidou in 2006. I’ve decided to reproduce this assembly of texts exactly as I submitted it to Nicole. — J.R. [8/23/08] Ten years later, my account of Tregenza’s filmography needs to be updated with a fourth feature, Gavagai (2016). [8/23/18]

Preface to Five Letters from Godard Apropos of Inside/Out

Not much (i.e., not enough) is known today about the three features of American independent filmmaker Rob Tregenza, all 35 millimeter—-Talking to Strangers (1988), The Arc (1991), and Inside/Out (1997)—- and possibly still less is known about Godard’s activity as a film producer, specifically of the third of these films. It isn’t even alluded to in Colin MacCabe’s detailed biography, where the fact that Godard helped to finance Straub-Huillet’s 1967 Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach equally goes unmentioned.

It also seems probable that the last film review published by Godard to date is his one of Talking to Strangers (see Jean-Luc Godard par Jean-Luc Godard, tome 2, 1984-1998, pages 355-356, where this text is undated, though it was written specifically for the Toronto Film Festival catalogue and published there in English in September 1996). Read more

This is the first article I ever wrote for Stop Smiling — their “auteur issue” (no. 23) in 2005. Like virtually all Welles reporting, this is of course drastically out of date, but often in a good way; it’s delightful to see how much more of his work has become available over the past 17 years. — J.R.

If Orson Welles were still alive, he would have turned 90 last May 6th. Chances are, no matter what he did in his final years, a certain number of people would still be griping that he never lived up to his promise. But I

wouldn’t be one of them.

This Midwestern whiz kid, a master of radio, theater, and film, terrorized the populace when he was 23 with a mockumentary radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds that was taken for real. At 25 he scandalized Hollywood with a first feature called Citizen Kane that ridiculed newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Welles was clearly expected to cause a sensation regardless of what he did after this. But to manage that, he would have needed continued public visibility, which Welles rarely had after those two early peaks. And in fact he was after more than sensation.

Read more

Posted by DVD Beaver in October 2007; I’ve updated many of the links. — J.R.

As with science fiction, the focus of my previous article in this series, the definition of what constitutes a fantasy film is to some extent arbitrary. Not every account of The Tiger of Eschnapur would situate it within the realm of fantasy, though I’d argue that a sequence involving a spider’s web that’s woven in the entrance to a cave, and perhaps other details as well, warrant such a description. The some goes for Confessions of an Opium Eater and its sudden shifts into slow-motion; these are nominally justified as opium-induced perceptions, but when the hero suddenly falls from a building and does several rapid cartwheels in midair, it’s impossible to tell at which point the logic of dreams takes over. In other respects, accepting Eyes Wide Shut as a fantasy is more a matter of interpretation than a matter of pointing at any obvious genre elements. And of course the realm of horror, which overlaps with fantasy without necessarily becoming fantasy (as in the cases of The Seventh Victim, Psycho, and Peeping Tom, for instance), accounts for at least four of my selections—Vampyr, Night of the Demon, The Masque of the Red Death, and Martin. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1990). — J.R.

Though crippled by studio recutting that tried to adjust this neurotic 1962 melodrama for the family market, Vincente Minnelli’s adaptation of Irwin Shaw’s novel is one of his last great pictures, reversing the Henry James model of innocent Americans encountering corruption abroad — it’s the Americans who are decadent here. Intelligently scripted by Charles Schnee, the film reunites the director, writer, producer (John Houseman), star (Kirk Douglas), and composer (David Raksin) of The Bad and the Beautiful, describing the attempted comeback of an alcoholic ex-star (Douglas), asked to help a director friend (Edward G. Robinson) with a new picture in Rome, who encounters both his destructive ex-wife (Cyd Charisse) and a redemptive young Italian woman (Daliah Lavi) in the process. George Hamilton plays a spoiled young actor who falls under Douglas’s tutelage, and Claire Trevor plays Robinson’s wife. The costumes, decor, and ‘Scope compositions show Minnelli at his most expressive, and the gaudy intensity — as well as the inside detail about the movie business — makes this compulsively watchable. 107 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Written for the Busan International Film Festival’s Korean Film retrospective catalogue, Fly High, Run Far: The Making of Korean Master IM Kwon-taek, Fall 2013. — J.R.

Preface

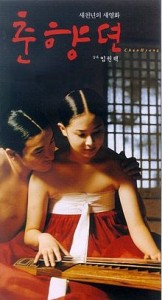

I can’t pretend to be familiar with Korean history in general and traditional Korean music in particular. But rather than attempt to disguise my ignorance with a handful of facts gleaned from superficial research, I prefer to approach Chunhyang (2000, 136 min.) in broader, more generalized, and less historical terms as a film confronting issues of representation relating to live performance as well as cinema, and the survival of relatively ancient forms of music and performance in the present.These are the issues that have drawn me to Chunhyang in the first place, despite an overall ignorance about Korean culture that extends to most of its cinema — including even most of the oeuvre of its most celebrated auteur, Im Kwon-taek.

I hope that this admission of my lack of knowledge and innocence can be regarded as a form of clarification and honesty rather than as an expression of arrogance. My theoretical assumption is that the most common form of journalistic bluff regarding such matters — conveying an unearned and unwarranted stance of authority, typically justified through a series of lazy intellectual shortcuts and/or appropriations (such as, for example, describing pansori as some Korean variant of the American blues) — is ultimately more imperialistic in effect than any honest admission of cultural ignorance. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 11, 2002, and then again on June 24, 2005, when Roger introduced it and led a discussion about it). Happily, this film is still available from Amazon and on YouTube, and in memory, it seems to get better and better all the time. — J.R.

There are so many curves and anomalies in this unpredictable low-budget independent feature (2001) by Chicago actor Michael Gilio that I’m tempted to call it an experimental film masquerading as something more conventional. If it’s a comedy — and I’m not sure it is — there are far too many close-ups, though this is also very much an actors’ film. If it’s a road film — and I’m not sure it is — it never gets very far on any given route, though that’s surely deliberate. Two characters (played by Gilio and Bullet on a Wire‘s Lara Phillips) are opaque — they meet at a convenience store where she’s shoplifting, then go on a cross-country trip toward LA, until things start to get weird — and two (played by Karin Anglin and the charismatic Rich Komenich) have backstories. This movie is about the interactions between these characters, and though I’m still trying to figure out what all the pieces mean, there’s no way I can shake off the experience. Read more

From the February 24, 2oo6 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

With the possible exception of Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, this 1937 drama by Leo McCarey is the greatest movie ever made about the plight of the elderly. (It flopped at the box office, but when McCarey accepted an Oscar for The Awful Truth, released the same year, he rightly pointed out that he was getting it for the wrong picture.) Victor Moore and Beulah Bondi play a devoted old couple who find they can’t stay together because of financial difficulties; their interactions with their grown children are only part of what makes this movie so subtle and well observed. Adapted by Vina Delmar from Josephine Lawrence’s novel Years Are So Long, it’s a profoundly moving love story and a devastating portrait of how society works, and you’re likely to be deeply marked by it. Hollywood movies don’t get much better than this. With Thomas Mitchell, Fay Bainter, and Porter Hall. 91 min. 16mm. Also on the program: McCarey’s silent comedy short Be Your Age (1926), with Charley Chase. Sat 2/25, 8 PM, LaSalle Bank Cinema.

Read more

Read more

The following was commissioned in 1999 by Written By, the magazine of the Writers Guild, which decided not to run it because Brooks’s agent refused to let me see The Muse in advance for this article unless a “cover story” was promised. Written By, to its credit, refuses to make deals of this kind. So the magazine paid me for the article and didn’t run it, which I hope made Brooks’s agent properly proud of his efforts. — J.R.

You may recall him as the wealthy convict in Out of Sight, or, prior to that, as Cybill Shepherd’s wisecracking cohort at the campaign headquarters in Taxi Driver, as Holly Hunter’s best friend in Broadcast News, or as the neurotic Hollywood producer in I’ll Do Anything. Maybe, if you’re luckier, you’ve seen his five underrated and highly durable comedies — Real Life (1979), Modern Romance (1981), Lost in America (1985), Defending Your Life (1991), and Mother (1996) — which will be succeeded later this year by The Muse.

Albert Brooks has so far taken solo writing credit only on Defending Your Life — sharing script credit with TV comedy writer Monica Johnson on the other four (as well as on The Scout, a disappointing 1994 baseball movie he didn’t direct), and also with Harry Shearer on Real Life, the first and probably the funniest of the lot. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 30, 2004). — J.R.

David Mackenzie’s compelling and authoritative adaptation of Alexander Trocchi’s 1953 novel revolves around a nihilistic bargeman (perfectly embodied by Ewan McGregor) who works the canals between Edinburgh and Glasgow and spends all his free time reading and screwing (often adulterously). This emotional detachment is often treated as an existential position, so the story occasionally suggests a beat version of Camus’ The Stranger, with the images’ sensual and erotic power often superseding any literal meaning. Despite the flashback structure, this is a film in which mood matters more than plot, while the hero’s heroic stature steadily shrinks. All in all, a very impressive second feature. With Tilda Swinton (The Deep End), Peter Mullan (My Name Is Joe), and Emily Mortimer. NC-17, 93 min. Century 12 and CineArts 6, Pipers Alley.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 7, 2005). — J.R.

Ten film critics’ polls in Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, Toronto, and Washington, D.C., have named Sideways the best movie of the year. I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

It’s not that I have anything against comedies; last year Down With Love was second on my ten-best list. Besides, Sideways has a dark side — its infantile hero (Paul Giamatti) steals from his mother, and his infantile sidekick (Thomas Haden Church), who’s about to be married, compulsively cheats on his fiancee. They behave as if the world beyond southern California doesn’t exist, but the movie doesn’t seem to realize it. And like most American mainstream movies, it dances around class issues without ever facing them.

If my colleagues who love this movie, many of whom I admire, are implying that it contains valuable life lessons, I wish they’d tell me what they are. Giamatti is an acerbic loser hero who’s eventually given a ray of hope, like the Woody Allen hero of 20 or 30 years ago but without the wisecracks. So is regressing to that moviemaking model the proudest achievement of world cinema in 2004? Did the critics find something comforting, even affirmative, about its provincialism? Read more