From Sight and Sound (Winter 1976/77). -– J.R.

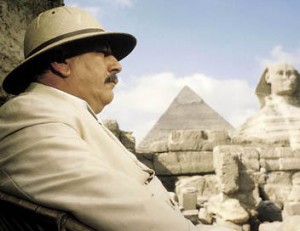

Jacques Tati, by Penelope Gilliatt

(Woburn Press, £ 2.95). A good example of Sunday supplement journalism, this thumbnail sketch — the first book in English devoted to Tati — shares roughly the same virtues and limitations as Gavin Millar’s Omnibus programme on him last spring: a warm, ample sense of the comic’s personality and opinions is coupled with a meagre grasp of his art. Basically derived from a New Yorker Profile, but decked out with a pleasant assortment of stills, Gilliatt’s slim volume hops from interview material to favourite recollected gags and back again without so much as hinting at the radical complexity of any single shot and its accompanying sounds in any Tati film, restricting its focus to a set of stray details retrieved out of context. To settle for this sentimental reduction of Tati’s genius is roughly tantamount to reducing [James Joyce’s] Ulysses to Joseph Strick’s greeting card version. But Hulot fans who feel that Tati’s importance rests chiefly on his charm as a performer should have little cause for complaint.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM