From the Chicago Reader (March 8, 1991). — J.R.

PRIVILEGE

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Yvonne Rainer

With Alice Spivak, Novella Nelson, Blaire Baron, Rico Elias, Gabriella Farrar, Dan Berkey, and Yvonne Rainer.

Approached as a narrative, Yvonne Rainer’s sixth feature takes forever to get started and an eternity to end. In between its ill-defined borders, the plot itself is repeatedly interrupted, endlessly delayed or protracted, frequently relegated to the back burner and all but forgotten. All the way through, the action proceeds like hiccups.

Yet approached as an essay, Privilege unfolds like a single multifaceted argument, uniformly illuminated by white-hot rage and wit — a cacophony of voices and discourses to be sure, but a purposeful and meaningful cacophony in which all the voices are speaking to us as well as to one another.

Everything in the movie can and should be experienced as part of an ongoing dialogue, and it’s no small tribute to its overall coherence and impact that one wants to have an ongoing dialogue with the movie–talk back to it, argue with it — and that one has to if the movie is going to make any sense at all. The dialogue may deliberately go in and out of sync with the on-screen characters, the characters may be periodically played by different actors, and the shots may shift without notice between color and black and white. One line of the argument may be interrupted or overtaken by another, and any given line may eventually prove to be a quotation, a part of the plot, a personal confession, a piece of invective, a nugget of factual information, a wisecrack, or some combination of the above. But one never, not even for a moment, loses touch with what this movie is about.

Through it all run two basic concerns — menopause and racism — and the discourse on them leapfrogs between rage and reflection, invective and analysis. The menopause in the story exists in the present, while the racism exists in the past. But in terms of the essay, past and present are so inextricably intertwined that we can’t establish any causal relationship between them; both simply coexist in the time of the film, as if the past racism and the present menopause were the two voices in the dialogue.

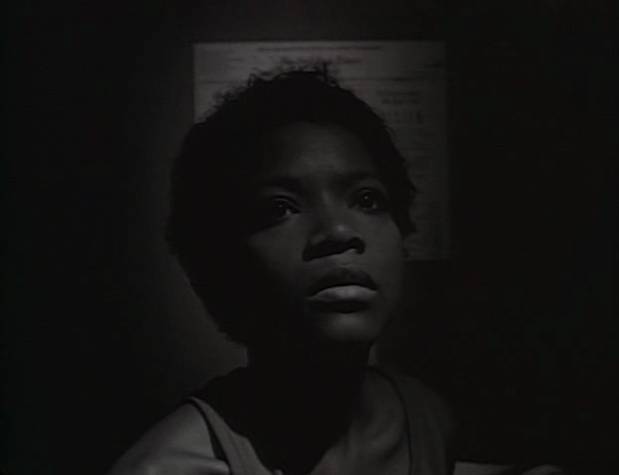

The essay is a lot more important, interesting, and persuasive than the story, but the essay needs the story in order to exist, and we need it, too, if we’re going to proceed any farther. In the barest of terms, the story goes something like this: a black filmmaker named Yvonne Washington (Novella Nelson) who is experiencing menopause decides to make a documentary about it, so she interviews her white friend Jenny (Alice Spivak), a former dancer who is also going through menopause. In the course of the interview, Jenny recounts something that happened to her 28 or 29 years ago — a “hot flashback,” as she calls it — that virtually becomes the film’s story.

In 1960 or 1961, Jenny moved into a second-floor apartment in a racially mixed New York neighborhood and became friendly with Brenda (Blaire Baron), a white lesbian and lab technician at Bellevue who occupied the apartment below hers. One night, Jenny heard a fight on the street below between a Puerto Rican couple, Carlos (Rico Elias) and Digna (Gabriella Farrar)–mainly Digna calling for help and for the police. Jenny called Brenda, who remarked, “Carlos and Digna are brawling again.” Eventually the police arrived — as Jenny saw, peeking through her blinds — and wound up arresting Digna and committing her to Bellevue.

Some time later, Carlos approached Brenda on the street and asked her if she could help get Digna out of Bellevue; Brenda replied that she didn’t know if she could, but she’d try. On a subsequent night, Jenny was wakened by Brenda’s scream downstairs, and this time she phoned the police rather than Brenda and went downstairs to wait for their arrival. Brenda later explained that she woke to the nude figure of Carlos standing over her bed. At a subsequent trial, Jenny committed perjury by falsely claiming that she’d seen Carlos in Brenda’s apartment. (He escaped through the window before the police arrived.) Carlos was sentenced to three or four months in jail and disappeared from the neighborhood, and Digna, as far as Jenny knew, remained in Bellevue. But after the trial the white upper-class assistant DA (Dan Berkey), who proved to be racist and sexist, asked Jenny out on a date, and they wound up having an enjoyable affair that lasted six months.

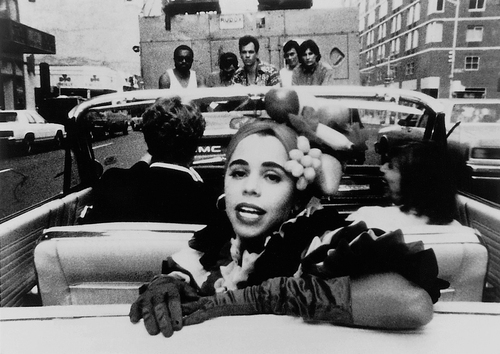

So much for the story, which is related piecemeal by Jenny to Yvonne Washington in a confessional manner, rather like a patient speaking to a psychotherapist. Interspersed with her account are Rainer’s own filmed interviews with white and black menopausal women; archival footage of white male doctors advising white women about menopause; statistics and other texts filmed off a computer screen; monologues delivered to camera by Carlos and Digna, the latter in a straitjacket; various clips, including one of Lenny Bruce doing a stand-up routine about gender differences; and diverse fantasy interludes, one illustrating a dream Yvonne Washington has and several others involving permutations of the remembered story (one in which Carlos is a white man, another in which Digna — at one point wearing a Carmen Miranda fruit salad hat — is continually present during Jenny’s affair with the assistant DA). There are also many kinds of music, ranging from an operatic aria to two separate versions of Chet Baker playing and singing “My Funny Valentine.”

Rainer’s tendency to retard her story with every means available has many honorable precedents, none of them currently very fashionable. Her strategies are modernist, and in this postmodernist era modernism is barely remembered, much less honored. A paragraph from Edmund Wilson’s Axel’s Castle may be helpful as a refresher course:

“Joyce has as little respect as Proust for the capacities of the reader’s attention; and one feels, in Joyce’s case as in Proust’s, that the longueurs which break our backs, the mechanical combination of elements which fail to coalesce, are partly a result of the effort of a supernormally energetic mind to compensate by piling things up for an inability to make them move.”

Fortunately, Rainer has created a 103-minute movie rather than a lengthy novel, and the longueurs, if any, are few and far between; but the other aspects of Wilson’s description still apply, and there’s another common point he fails to mention here — the derivation of plot and characters from personal, autobiographical material. Rainer, who is the same age as Jenny and Yvonne Washington, is both a filmmaker and a former dancer. In this respect, the film’s dialogue is a dialogue she’s having with herself; but because Rainer is white and Washington is black, it’s an imaginary dialogue predicated on the fiction that Rainer has a black alter ego.

Privilege is without a doubt the most accessible and entertaining film made to date by the best-known and most respected avant-garde filmmaker working in New York. (Rainer is the recent recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant, and a book documenting and analyzing her five previous features, The Films of Yvonne Rainer, was published by Indiana University Press a couple of years ago.) Nevertheless, the film (which played at the New York and Toronto film festivals last year) isn’t opening commercially in Chicago but is showing only twice at the Film Center, as the opening attraction in the tenth annual Women in the Director’s Chair film and video festival. And it’s a sobering indication of how little Rainer’s credentials count in the world at large that when Variety reviewed Privilege last year, it misidentified her as an “Afro-American” filmmaker and didn’t deem the error important enough to run a correction afterward.

If the maximum audience anticipated for Rainer’s most accessible work in the Chicago area is only enough for two screenings — as opposed to, say, the more than 115 screenings of a piece of junk like King Ralph over the past week alone — then it seems reasonable to surmise that a thoughtful entertainment about menopause and racism is considered no more than one fifty-seventh as important as a thoughtless entertainment about a slob pianist from Las Vegas becoming the king of England. If the reader will allow me to play a little of Rainer’s game and conduct a dialogue with a fictional version of myself, a few possible reasons for — and responses to — this state of affairs might emerge.

John Q. Public (“Q” for “querulous”): As far as I’m concerned, the most immediate turnoff that can exist in movies today is “political correctness.” Who wants to be preached to by an angry 57-year-old feminist who can’t even tell a story straight, and who chooses to regale her already converted, artsy-fartsy liberal audience with a series of heavy guilt trips? Isn’t it reasonable to assume that after a hard day’s work, any spectator willing to hire a baby-sitter, brave the traffic, and look for an expensive parking space is likely to be happier munching popcorn while laughing at John Goodman trading quips with a spear-chucking African king?

Jonathan Rosenbaum: What do you mean, “political correctness”? Part of what’s exciting and daring about Privilege is that Rainer has the guts and nerve to dive straight into a hornet’s nest, “political correctness” be damned. In fact, part of that already converted, artsy-fartsy liberal audience you mention has already been laying into her for her political incorrectness. How dare she, runs the argument, presume to speak for black people by presenting us with Yvonne Washington? And if she means to honor what black people have to say, why does she devote so much attention to the sexist diatribes of Eldridge Cleaver that extol rape and excoriate lesbians? The list of her potential outrages could run on indefinitely. Anyway, “political correctness” has by now become one of those meaningless buzz terms used to bash anyone slightly to the left of Ronald Reagan. And King Ralph is arguably an even more didactic movie than Privilege, preaching to the converted that good old let-it-all-hang-out American male vulgarity, innocence, and stupidity are preferable to English restraint and good taste, and get rewarded hugely besides.

JQP: Correctness doesn’t have to be political. For that matter, what’s so political about menopause, for God’s sake? It’s a fact of nature.

JR: That only proves you should see Privilege. Menopause becomes political at precisely the point where male “experts” control its social definition — Rainer has plenty of hilarious and frightening archival clips of these “experts.” And you can’t ever accuse Rainer of simply attacking familiar feminist and leftist targets and letting herself off the hook. At one point, describing her affair with the assistant DA, Jenny remarks, “I was ready to sell my soul for a mess of potage — a mass of penis.”

I suppose you could say that being black is a fact of nature, too, but the minute a society defines what being black means socially, that definition has immediate political consequences. Privilege deals with other kinds of privilege as well: not just the privilege of being white and male, but the privilege of being young and well-to-do.

Sure, Rainer is political, and she makes no bones about it. (This is a vast improvement over her first four films, which were about politics without being political in the same way. Ever since she turned a corner in her last film, The Man Who Envied Women, in 1985, some of the avant-garde film critics — mainly the ones who are every bit as antagonistic to politics as their mainstream counterparts — haven’t let up on her.) King Ralph, which is equally political in its insistence on what being American or being English means, isn’t up-front about its political agenda at all.

JQP: Why should it be? The point of King Ralph is to forget where you are and who you are for a couple of hours.

JR: Agreed. And I’m equally sure that for some of those artsy-fartsy types, Privilege can and does serve exactly the same function.

JQP: I wonder about that. The first job of any filmmaker worth his or her salt is to make you believe in a story, regardless of whether it happens to be true or not. Rainer doesn’t even try. For example, when we see the flashback of Jenny in her 20s, she’s played by the same actress who plays her in her 50s. Even her makeup is the same!

JR: As Jenny puts it herself to Yvonne Washington, “Are you gonna hold up this show for some expensive illusionism? Let’s get on with it.”

JQP: That “expensive illusionism” you and Rainer are sneering at is what people pay to see in movies like King Ralph.

JR: I know — even when the story itself is too pea-brained for a ten-year-old to believe in. But let’s be fair: I already said that Rainer was an essayist, not a storyteller. But Rainer can be something of an illusionist, even in an essay form and on a low independent budget.

JQP: What do you mean?

JR: Eight years ago, when I was teaching at Berkeley and I showed my students Rainer’s Film About a Woman Who . . . (1974), some of them accused her of New York provincialism. I’ve been thinking about that charge for a long time — the charge that some New Yorkers are so convinced that they’re living in the vital, exclusive center of the universe that they wind up displaying a certain shortsightedness.

After sitting through about 95 percent of Privilege, I had decided that this charge, if it was ever true of Rainer, no longer applied to her present work. Then just before the final credits started to roll, she cut to her wrap party: her actors, her crew, and various friends whooping it up and enjoying each other’s company, with occasional camera zooms into individual clusters that emphasize the fact that the whites and nonwhites appear to be in perfect harmony. She periodically cuts back to this party, and then she cuts to a brief text on a computer screen: “UTOPIA: the more impossible it seems, the more necessary it becomes.”

It’s a moment that reminded me of the supreme deflation that occurs at the climax of Hegel’s theoretical work. Just think of it: perhaps the last great mind in the Western world capable of mastering all existing knowledge developing a dialectical theory of history that claimed that every previous era yielded its opposite and then produced a grand synthesis, again and again — finally yielding what Hegel saw as the ultimate utopian golden age: the corrupt Prussian state and dismal period in which he himself was living. On a much smaller scale, Rainer’s postulating her wrap party as a possible vision of utopia struck me as illusionistic, self-regarding chutzpah par excellence — unless I misconstrued what she was getting at.

JQP: Art looking at its own navel, hunh? That’s what I hate about the whole artsy-fartsy scene.

JR: Maybe, but John Goodman’s navel in King Ralph is a whole lot bigger and more prominent; and if you start thinking about the white American male navel more generally, you’re talking global politics.

The fact is, even though Rainer may not be a “natural” filmmaker, she’s one hell of a writer and a sharp dialectical thinker, testing her own limits and those of her audience every step of the way and producing a lot of new ways of thinking about things in the process. With the possible exception of that wrap party, her entire movie is a continuous quarrel with herself and her audience that’s continually sending off sparks, waking us up, obliging us to dive into the hornet’s nest along with her. What she’s doing, like it or not, is outrageous. By contrast, King Ralph‘s sense of the outrageous is so mundane and familiar that it literally put me to sleep.

JQP: That’s exactly what I’m looking for: rest and relaxation. So I hope you’ll excuse me if I run off to see King Ralph for the third time.

JR: That’s your privilege.