From the Chicago Reader (January 10, 1997). — J.R.

Compiling a list of the best new (or “new”) movies that opened in Chicago in 1996, I’ve come up with 40 titles, half of which are foreign-language pictures. Many of my colleagues would regard choosing so many foreign movies as perversely esoteric, but it’s hard for me to fathom why. I willingly concede that this country has one of the strongest national cinemas in the world — probably the greatest, which is fully reflected in my including 19 American films in my list and only 5 from France; 3 from Taiwan; 2 apiece from England, Hong Kong, and Iran; and 1 each from mainland China, Denmark, Italy, Poland, Russia, Spain, and Vietnam.

Of course I haven’t seen nearly as many non-American films as American, but I’ve made a stab at seeing those that have made it to Chicago. I have long been bewildered by how the majority of my colleagues almost never mention any cinema that isn’t English-language when they draw up their end-of-the-year lists. Is American cinema really that wonderful and non-American cinema really that awful? Of course not; the reason most reviewers don’t include foreign pictures on their lists is that they don’t see them. And why not?

The usual explanation is that the American public isn’t interested, but this strikes me as the kind of circular reasoning that would never be countenanced in any other art form. How can the American public be interested in something it never hears about? A better explanation, I think, is that most reviewers want to avoid alienating their editors — who are usually looking for column inches about what the public already knows about thanks to advertising. Blaming the public for this state of affairs is simply passing the buck.

What we’re ultimately talking about is business, and the kind of discourse that business tolerates. To appreciate how we arrived at this juncture, consider that in 1938 the U.S. government filed an antitrust action against Paramount Pictures, objecting to the monopoly the studio had on movie theaters. By the end of 1946 a court judgment enjoined not only Paramount but Loew’s, RKO, Warner Brothers, and 20th Century-Fox from acquiring additional theaters. This had many consequences, the most important of which was a substantial reduction in the control Hollywood studios had over what moviegoers saw in theaters. Paramount, which controlled the largest of the studio-run theater chains, had nearly 1,500 theaters in the late 40s; by 1957 it had a few more than 500. By the early 60s the more open market created by the ruling led to many more independent theaters, including art houses that specialized in foreign films. They tended to flourish because they rented films for a flat fee rather than on a percentage basis, which granted exhibitors and programmers a lot of creative freedom when it came to what they could show. I grew up in a family that ran a chain of movie theaters in northwestern Alabama. My grandfather had partners in Tennessee who owned other theaters, and because they held a monopoly on theaters in that part of the south, they were sued by the government as a test case in the late 40s. They were forced to dissolve their partnership, and in 1956 my grandfather reluctantly made his chain independent, which it remained until he sold the theaters in 1960. During those last four years these theaters showed more foreign-language pictures than they ever had before. Art cinemas were springing up all across America, a movement spearheaded by the enormous success in 1946 of two Roberto Rossellini masterpieces, Open City and Paisan, each of which grossed close to a million dollars in the U.S. — an enormous sum in those days. By the time my family’s business became independent, there were hundreds of these art theaters in America, and by the late 60s there were more than a thousand. Many of these theaters later became repertory and revival houses, and during the 70s they began to show midnight movies such as Night of the Living Dead, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and Eraserhead — which was possible only because the theaters were independent. But the Justice Department under the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton administrations has consistently refused to enforce antitrust laws, which has shrunk the market for independent theaters. The alternative venues now playing foreign films and midnight movies are shadows of their former selves. In Chicago only four commercial theaters now show midnight movies on a regular basis and only two show new foreign-language films (not counting noncommercial venues such as Facets Multimedia and the Film Center).

In the past month only two first-run foreign-language pictures have been playing in town, both French — Ridicule and Thieves. Should one conclude that the reason the American people supported more than a thousand art theaters in the late 60s and support no more than a handful now is that they liked foreign films then and they don’t today? Is it simply because, as so many New York provincials like to argue, foreign movies were better back then? Both explanations strike me as refusals to look at central facts about a free economy. When antitrust laws were enforced, independent theaters–and therefore independent movies — flourished; now that the laws aren’t being enforced, studios and their subsidiaries monopolize our cultural choices however they see fit. Calling this “the will of the people” is chicanery; it’s the rough equivalent of saying that Bill Clinton and Bob Dole represented the only ideological desires of the American populace — conveniently overlooking the billions of dollars that placed them on the ballot. This is why my list of the year’s best movies consists of write-in votes — designed not to win any election but to explain what still interests me about movies (not things I’ve found in the English Patients, the Jerry Maguires, and even the Shines out there). Except for the top and the bottom of the list, all my choices are given in pairs; in most cases I’m linking them because they represent specific categories of what I value, though the film I cite first is generally the one I prefer.

***

1. Dead Man. Appropriately, the key independent movie of the year stands alone. I’ve cheated a little in my tally by including Jim Jarmusch’s visionary western as a foreign-language rather than an English-language picture, because it includes dialogue in several different Native American languages, none of it subtitled. Besides, this movie was treated by most American critics as if it were a foreign picture (not surprising given that this country typically treats Native Americans as foreigners). And it’s worth adding — in response to the bum rap that the “American public” rejected Dead Man, the word put out by the distributor after it wasn’t allowed to recut the film — that it’s been running continuously in Chicago ever since it opened in June, mainly as a midnight movie. (I suppose you could say that the American public rejected Moby-Dick too, since the first printing sold only 500 copies.) A scary and beautiful black-and-white feature that turns the mythology of the American west on its head, Dead Man is a bold departure for Jarmusch, formerly known as a refined minimalist whose films coasted along on their behavioral charm. Though this film has behavioral charms of its own (chiefly Gary Farmer’s charismatic performance as a maverick Indian named Nobody), its vision is considerably darker. As Kent Jones wrote in Cineaste, “There is no American West. There is only a landscape that America the conqueror has emptied of its natives and turned into a capitalist charnel house.” Shot through with a terse gallows humor and a feeling for figures in landscapes worthy of Anthony Mann, this is a spiritual epic about one man’s journey toward death that only grows in power and meaning with repeated viewings.

2. Kira Muratova’s The Asthenic Syndrome (1989) and Kryzysztof Kieslowski’s The Decalogue (1988) took their time reaching Chicago (though The Decalogue was screened at the 1989 Chicago International Film Festival), but neither seemed dated when it finally surfaced. If Jarmusch’s masterpiece deserves to be considered in part as a state of the union address (albeit one punctuated by wisecracks and quotes from William Blake), Muratova’s angry poetic look at postcommunist Russia, which showed at the Film Center in September, could just as easily be called a state of the disunion lament; a related impulse can be found in Kieslowski’s more ironic examination of Old Testament morality in postcommunist Poland, which showed at Facets Multimedia in late March and early April. Both were works that I carried around in my head for weeks, and if in retrospect Muratova’s film seems greater, this may be because her achievement is more original and more what the French call “cinematographic” — that is, more a matter of sound and image and less a matter of deft screenwriting (as is the case with the work of Kieslowski and his gifted cowriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz). Moreover, Muratova’s astonishing notion of extreme passivity (narcolepsy) and extreme aggressiveness (violence) loose in her characters’ world corresponds more closely to a global perception, with applications apparent everywhere one turns. The Decalogue is a work of consummate mastery, and it launched Kieslowski’s international reputation. But I suspect that Muratova’s relatively out-of-control masterpiece will be remembered 30 years from now as a better portrait of the late 20th century.

3. Charles Burnett’s Nightjohn and Terence Davies’s The Neon Bible are both by gifted, crotchety filmmakers working far outside their usual stomping grounds and scoring spectacularly more often than not. Nightjohn, a feature made for the Disney Channel about plantation slaves surreptitiously teaching one another how to read, turned up in the Black Harvest festival at the Film Center in July and by now should be available on video. Emotionally and expressively, this sincere and highly effective piece of agitprop (written by Bill Cain) deserves to be regarded as Burnett’s mainstream triumph, even if most mainstream critics, too busy catching up with pieces of dead matter like The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Mission: Impossible, ignored it. Unlike Nightjohn, The Neon Bible — a luminous rendering in ‘Scope of a not very distinguished novel set in Georgia in the late 30s to the mid-40s — can’t be regarded as a triumph of storytelling, because it doesn’t have much of a story and because Davies’s remarkable talents have very little to do with narrative. His genius, already evident in his masterpieces Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes, is for creating and conveying highly intense, rapturous moments of illumination, and The Neon Bible, which isn’t a masterpiece, gave me several that I’ll treasure for years. The unlikely ingredients of these lyrical transports include perfectly imagined crowds on a small town’s main street and inside a revival meeting, Gena Rowlands singing “My Romance,” a shot combining recollected snow falling and a boy in a room in a stunning diptych worthy of Joseph Cornell, and a bedsheet flapping on a clothesline to the accompaniment of the theme music from Gone With the Wind. For any one of those moments I’d happily trade the collected works of John Sayles, John Schlesinger, and the Coen brothers, and I might even throw in Gone With the Wind itself. Davies’s exquisitely distilled poetry, always hard won and therefore precious, negates the need for such photogenic clutter.

4. Abbas Kiarostami’s 1981 short film Regularly or Irregularly and Mark Rappaport’s From the Journals of Jean Seberg, which turned up at the Film Center respectively in June and January, are potent and subversive examples of the fusing of nonfiction and fiction–an ontological project that underlies all filmmaking to some degree, but rarely in a manner that reveals the philosophical contradictions of the undertaking, something both these films do. Kiarostami’s simple yet profound and witty 15-minute demonstration (the title of which an Iranian friend tells me would be more accurately translated as “Orderly or Disorderly”) alternates takes of children leaving school, lining up at a water cooler, and boarding a bus, as well as pedestrians and drivers negotiating city traffic — all in orderly and disorderly fashions — with Kiarostami and his camera crew commenting offscreen on their work. Kids boarding a bus in an orderly manner in long shot looks like documentary, but the same kids boarding the same bus in a disorderly manner in medium shot looks contrived, like fiction — yet for all we know, both impressions could be false. Rappaport’s intricate, multifaceted fictional essay about a real actress perceived through the fictions of her movies and the ambiguous facts of her life, told mainly through clips and recitations by Mary Beth Hurt, explores the delicate transactions between ethics and aesthetics without ever letting us feel assured that we know which is which.

5.Thieves (1996) and My Favorite Season (1993) — the 13th and 11th films of André Téchiné, both starring Daniel Auteuil and Catherine Deneuve — are the two best French films to open in Chicago last year (they opened at the Music Box in December and June respectively) and the two best Téchiné films I’ve seen (the only other contender would be his 12th, Wild Reeds, released here in 1995). Both are dense, passionate, polyphonic works about love, sex, and destiny inside and outside the snares of family life; both are beautifully acted and powerfully composed as narratives. If you opted instead for reductive adaptations of prestigious novels in English, which is what most big-time distributors and reviewers were pushing more, I hope they at least kept you awake.

6. Jafar Panahi’s The White Balloon (at the Music Box in March) from Iran and Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Goodbye South, Goodbye (at the Chicago International Film Festival in October) from Taiwan: two more movies about the way we live, both charted in relation to locomotion and the flow of real time. A little girl seeks to purchase a goldfish to celebrate the New Year in the streets of Tehran; a group of entrepreneurial gangsters and swindlers in Taipei travel to the country as part of a scam involving pigs, and one of them fights with his family, leading to endless recriminations, grudge matches, and more deals. The plots of both movies are fairly gratuitous, while the gracefully composed textures of personal interactions, settings, and “dead” moments are everything. First-timer Panahi, starting with a script by Kiarostami, works with real time and how it’s perceived by a fanatically focused seven-year-old; master Hou — working with his usual writer, novelist Chu Tien-wen — explores the placelessness of travel by train, motorbike, and car, and of messy bedrooms and loveless, dingy bars in the sticks, conjuring up the whole rootless horror of what business is doing to Asia.

7. Two complex historical afterthoughts about the meaning of communism on opposite sides of the world: Li Shaohong’s beautifully framed Blush (at the Music Box in October), about the fate of two Shanghai prostitutes and one of their wealthy clients after the 1949 revolution, and Thom Andersen and Noel Burch’s freshly conceived and thoughtfully compiled video documentary Red Hollywood (at the Film Center in August), about the social content of Hollywood movies written or directed by communists.

8. Two sharp American experimental features: Hal Hartley’s multilingual Flirt (at the Music Box in November) and James Benning’s Deseret (at Chicago Filmmakers in March). Flirt is expansive in space, leaping from New York to Berlin to Tokyo to recount three witty permutations of the same story. Deseret is expansive in time, encompassing the recitation of stories from the New York Times between 1852 and 1992 about the area that’s now Utah, its landscape and detail captured today by Benning’s discerning eye. Both directors had original notions of how to put together a feature that make their films closer to interrelated story collections than novels; Flirt is really a collection of three short films, Deseret an assembly of 93 shots and stories.

9. Billy Bob Thornton’s Sling Blade (Music Box, November and December) and Jacques Rivette’s two-part 1993 Joan the Maid (Film Center, January): two very practical accounts of individual saintlike purity functioning in messy worlds. It might be argued that Thornton’s hero (perfectly played by Thornton himself) is, for all his simple goodness, no Joan of Arc, while Rivette’s Joan of Arc (Sandrine Bonnaire), for all her simple mulishness, is no southern half-wit; but the style of both filmmakers is admirably scrupulous and nuanced in spelling out what their noble protagonists have to contend with, including violence and sexual politics. Sling Blade turned up briefly for Oscar consideration and is expected to turn up again; the two features comprising Rivette’s Joan the Maid — “The Battles” and “The Prisons” — will probably come out here on video when hell freezes over. (We’ll probably have better luck with Rivette’s subsequent Up Down Fragile, which made my ten-best list last year, thanks to distribution by the resourceful Cinema Parallel.)

10. Mike Leigh’s Secrets & Lies and Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat, two movies about middle-class black protagonists becoming integrated into white worlds, may not really belong together, but I don’t know where else to put them. Leigh’s Ibsenesque comedy-drama of family revelations and accommodations in London (which opened at Pipers Alley in October right after a Chicago International Film Festival screening) held up for me over three viewings, but still struck me as inferior to his High Hopes (which ranked fifth on my 1990 ten-best list) and Grown-ups (1990), a TV film that used Brenda Blethyn to better effect (which tied for ninth place on my 1993 list). Leigh’s first mainstream hit certainly engaged and entertained me, but it didn’t challenge or enlighten me as those earlier films did, perhaps because Leigh no longer has Margaret Thatcher to work up steam about. Having scant interest in and even less sympathy for Julian Schnabel as a painter, I expected little from Basquiat, which opened at the Fine Arts in early September, but I was surprised to discover how fresh and interesting it was as filmmaking. Not since the credits sequence of Seven have I seen experimental techniques for sound and image put to such intelligent use in a commercial feature. However scattered the results may be as narrative, this odd biopic is packed with arresting ideas, some of them even about the art world.

11. Get on the Bus was Spike Lee’s welcome return to his independent roots, and Chungking Express was Wong Kar-wai’s first crack at American distribution, thanks to Quentin Tarantino. Neither of these topical and kaleidoscopic works showed the filmmaker at his best (check out Do the Right Thing and Days of Being Wild), but both were energetic looks at modern life.

12. Mars Attacks! and The Cable Guy were the two gutsiest expensive studio releases in a moribund year for the mainstream, both of them turning on the media itself and thus predictably occasioning almost identical negative reviews from the New York Times‘s gatekeeper Janet Maslin, who actually chastised Jim Carrey for not making another Ace Ventura movie (though she’d previously expressed contempt for both Ace Ventura movies). Most of her colleagues gave similar advice to Carrey and Burton — giving birth to a new genre of career management under the guise of film reviewing — proving that reviewers are more answerable to the studios than to their readers (who might, after all, have been on the lookout for something bold and original). Tim Burton’s attractively fashioned spitball, written by Jonathan Gems, had the temerity to mock Colin Powell as a wimpy careerist bureaucrat and to celebrate little green men sucking up our nuclear capability in a crack pipe; Carrey’s dark look at the nature of his own appeal and TV pathology in general –directed by Ben Stiller from a Lou Holtz Jr. script — also sent the flacks running for cover. I salute both Burton and Carrey for their reckless courage and insight.

13. Ethical wisdom wasn’t exactly a cottage industry in 1996, so Sara Driver’s gentle ghost comedy When Pigs Fly and Tim McCann’s thoroughgoing critique of macho foolishness, Desolation Angels, got overlooked in the mad rush to acclaim Flirting With Disaster as corrosive satire. It didn’t help that Driver is both a surrealist and a woman (an ignored combination in most critical lexicons) or that McCann skewers women as well as men for their oafish behavior around the altar of comic-book masculinity.

14. Apart from Dead Man, the two best literary movies of the year were Bernardo Bertolucci’s Stealing Beauty (about the daughter of a woman poet), gracefully scripted by novelist Susan Minot, and Gerard Mordillat’s My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud, cowritten by critic Jerome Prieur, with Sami Frey memorably incarnating the mad and intractable playwright-poet-theorist.

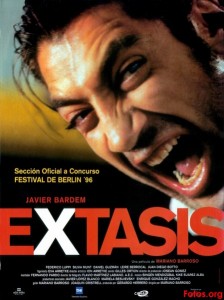

15. It’s harder than usual to be young and rootless today, and Mariano Barroso’s Ecstasy and Tsai Ming-liang’s Vive l’Amour were adroit, affecting accounts of being young and rootless in two precisely defined milieus — the theater scene in Madrid and the real estate business in Taipei.

16. I was so stimulated by the aggressive stylistic challenges of Tran Anh Hung’s Vietnamese Cyclo (an expressionist look at poverty and violence in Ho Chi Minh City) and Lars von Trier’s Danish Breaking the Waves (a postmodernist look at religious faith and sexual degradation on the northwest coast of Scotland) that I probably overrated both of them while rationalizing their commercial crassness. Nevertheless my struggles with both were rewarded up to a point — far more than my struggles with the commercial crassness of, say, Oliver Stone and Alan Parker, whose taste for stylistic bombast offers fewer lasting dividends, except to their investors.

17. Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Mieville’s 2 X 50 Years of French Cinema (a video) and Arthur Miller and Nicholas Hytner’s The Crucible were both thoughtful efforts to deal with national histories at a time when amnesia prevails. Godard and Mieville went all the way back to Diderot in tracing a kind of French writing related to cinema, and Miller and Hytner’s visually striking drama of mass hysteria related not only to the Salem witch trials of 1692 but to the anticommunist purges of the early 50s (when Miller’s original play was written) and subsequent puritanical frenzies in this country.

18. Good quiet movies about character tend to be as underappreciated and neglected as movies displaying ethical wisdom (see number 13). Richard Pearce’s A Family Thing (written by Billy Bob Thornton and Tom Epperson) and Claude Sautet’s Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud (written by Sautet, Jacques Fieschi, and Yves Ulmann) are both exquisitely performed two-handers, and the subtleties of James Earl Jones and Robert Duvall (along with the fabulous Irma P. Hall) in the first and Michel Serrault and Emmanuelle Beart in the second deserve lasting recognition.

19. Stanley Kwan’s video documentary from Hong Kong, Yang and Yin: Gender in Chinese Cinema, is a fascinatingly personal (if incomplete) take on Chinese-language cinema — the most vital and diverse to be found in the world right now, apart from the American and the French. Red Lotus Society, Stan Lai’s Taiwanese feature about vaulting and contemporary Taipei, shot by the kinetic Chris Doyle, is one indication of that vitality.

20. Finally, three singular youth movies, the first two of which sped through town so quickly you might easily have missed them: Annette Haywood-Carter’s dreamy and beautifully lit Foxfire (written by Elizabeth White), Wes Anderson’s funny and upbeat Bottle Rocket (cowritten by Owen C. Wilson, one of the lead actors), and Danny Boyle’s edgy and exhilarating Trainspotting (written by John Hodge).

***

These aren’t the only good new movies I saw in 1996; I could also make cases for, among others, Knocks at My Door, Curtis’s Charm, and Guimba the Tyrant. And old good ones were plentiful as well; Facets Multimedia and the University of Chicago’s Doc Films outdid themselves in serving up such specialties as retrospectives devoted to Robert Bresson, Bela Tarr, and post-Hollywood Orson Welles. Turning to my annual F.W. Murnau award for the movie or movies that did the most to alter my sense of film history, let me cite the restorations of two French masterpieces of the 60s, both of which looked better in 1996 than ever before: Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), which opened at the Music Box in May, and the 70-millimeter version of Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967), which ran at the Film Center in December. Both offered good reasons for being alive, remaining so alert to the world outside the movie theater that seeing them wasn’t an escape but an enhancement.