From American Film (May 1978). – J.R.

What’s been happening to British film production lately? If one tries to sort out the myriad confusions of financing patterns, it seems possible to arrive at two diametrically opposed conclusions — depending upon where one happens to be sitting and who one happens to be listening to. One conclusion says that things look bleaker than ever, with no genuine relief in sight. The other sees a renaissance of British filmmaking just around the corner.

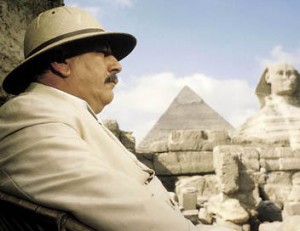

On the one hand, toting up the investments of British capital in expensive feature productions, things seem to be unusually active. The brothers Lord Lew Grade and Lord Bernard Delfont seem to be leading the pack with their respective companies, ITC and EMI, preparing such extravaganzas as Franklin J. Schaffner’s The Boys From Brazil (ITC) -– starring Gregory Peck, Laurence Olivier, James Mason, Lilli Palmer, and Uta Hagen — and Death on the Nile (EMI), another all-star special featuring Peter Ustinov, Jane Birkin, Bette Davis, Mia Farrow, Jon Finch, Maggie Smith, David Niven, and Angela Lansbury, under the direction of John Guillermin. Even the long-restive Rank organization has been getting back into financial participation.

On the other hand, where’s the indigenous British product? Quintessentially British movies like Room at the Top, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, This Sporting Life, A Taste of Honey, The L-Shaped Room, and Darling no longer appear to be in the offing, since both the home and foreign markets for such pictures have evaporated. Even remakes of Hitchcock’s celebrated British classics The Thirty-Nine Steps and The Lady Vanishes that are being planned are described by Rank executive Edmond Chilton as “international in character,” while other Rank projects include “three original screenplays to be made entirely on location in Yugoslavia, India, and Mexico.”

At the other side of the spectrum is Ken Wlaschin, program director of the National Film Theatre, who introduced last year’s London Film Festival in the following manner: “The British film industry is alive and well and hiding out under the name ‘independent cinema.’ . Perhaps the film moguls and the government don’t realize it yet (certainly the movement could use a lot more financial encouragement) but independent British cinema is flourishing all over.

In between these extremes are such forces as the Association of Independent Producers (AIP). It came into being about a year ago in response to the assistance of the British government in the financing of domestic productions. Chiefly representing the medium-budget filmmakers whose efforts fall into neither the blockbuster nor the underground categories — and boasting a list of members that includes everyone from Lindsay Anderson, Bryan Forbes, David Warner, and producer Milton Subotsky to Barney Platt-Mills, Werner Herzog, Sam Peckinpah, and animator Bob Godfrey — this new pressure group has been interested in charting procedures whereby financing needn’t run into some of the obstacles that it currently encounters.

The latest project of the AIP, “The New Deal,” is a proposed business plan intended to protect first investors and to encourage producers to take more initiative and responsibility for the distribution of their fllms. Attempting to set up a system in which investment, production, and exhibition can all operate in a more co-ordinated and mutually beneficial manner, this proposal is only the most recent of several efforts within the British film industry to pool and reorganize its resources.

***

As for the London filmgoing scene, the overall situation for the spectator looks nearly as promising as it did when I wrote my last ” Letter from London” a year ago. A major loss was the closing of The Other Cinema last Christmas due to an insuperable lack of funds. Nevertheless, the fact that this ambitious organization kept afloat for roughly a year — premiering such offbeat items as Jean-Luc Godard’s Number Two, Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo’s Winstanley, and Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey’s Riddles of the Sphinx, and alternating with weekend discussions and a wide range of revivals — is itself no small achievement.

Another enterprising new cinema, the Camden Plaza, has opened in Camden Town and has been offering such fare as Paolo and Vittorio Taviani’s Padre Padrone, an adventurous pairing of Robert Bresson’s The Devil, Probably with Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s short Every Revolution Is a Throw of the Dice,and revivals of Max Ophüls’s The Earrings of Madame de . . . and Lola Montes. Operated by Andi and Pam Engel (whose new distribution company, Artificial Eye, has been handling everything from the latest Resnais and Buñuel to such rare classics as Dziga Vertov’s A Sixth of the Earth (1926) and Slaton Dudow and Bertolt Brecht’s Kulhle Wampe (1932), the Plaza represents only one landmark in the current London film scene that continuesto make distribution of continental European films in America seem relatively meager.

Still another cinema is the Screen on the Hill-two tube stops north of the Plaza, in Belsize Park-which opened early this year with the remarkable swan song of the late Luchino Visconti, The Innocent. Adapted from a novel of that title by Gabriele d’Annunzio, this somewhat unexpected masterpiece begins, behind the credits, with the director’s own hand emerging from the bottom of the frame to turn the pages of this book. What follows is an elegiac and finely tuned melodrama of Roman society at the turn of the century that can be read as an intensely personal and self-critical reflection by Visconti on the contradictions of his own position as an upper-class Marxist. Depicting the tragic self-deceptions of a romantic “free thinker” (played by Giancarlo Giannini) whose love for his wife (Laura Antonelli) perversely leads him to murder her illegitimate child, this contemplative and erotic late work is the last thing one might expect from Visconti, after the bombast of The Damned and Conversation Piece. Released in Italy and France three years ago, its continued absence from American screens is indeed unfortunate.

But if England still seems ahead of the United States in foreign releases, this is not to say that the prognosis for the future is necessarily hopeful. The difference may only be that a few more distributors in England are willing to take the risk of “thinking small.” And, as independent distributor Derek Hill pointed out last year in Sight and Sound, anyone who considers bringing a subtitled color feature into England today would be unwise to allow less than £3,000 for costs, and would be equally unwise to count on more than £2,500 as revenue. Consequently, “Those in it for the money must soon pack it in. Those in it for love seem likely to be wiped out. Rising costs and falling audiences suggest that within two years, maybe only one, there could be virtually no more subtitled films imported into Britain.”

A gloomy forecast. Yet if one sets this alongside the unusually popular audience responses to Padre Padrone and The Innocent in London, it becomes difficult to gauge which telltale signs are the crucial ones. As with the question of future British production, a lot depends on whomever you happen to be listening to at any given moment.

***

There are reasons to inquire into the future of the government-supported, strife-ridden British Film Institute as well, now that its director, Keith Lucas, has announced his departure in September (with no replacement chosen as yet), and the various departments of the institute are seemingly recovering some of their former autonomy-after an attempt by Lucas to centralize BFI activity — through their relocations in separate buildings along Dean Street and Charing Cross. At the same time, there is plenty of evidence here as well of purposeful projects in different sectors: a lively new series of paperback monographs published by the BFI on subjects ranging from Dreyer, Pasolini, and Rivette to “Gays and Film” and such neglected British filmmakers as Walter Forde, Frank Launder, and Sidney Gilliat; exhaustive and simultaneous retrospectives devoted to Kenji Mizoguchi and Fritz Lang at the National Film Theatre. (The latter, which had me dashing from the first half of Lang’s serial The Spiders in NFT-1 to Mizoguchi’s silent The White Threads of the Waterfall in NFT-2, proved to be exhausting as well as exhaustive.) However one slices it, forecasting either doom or resurgence, the London film scene appears to be just as lively as ever.