I suspect that the easiest money I’ve ever made in my

entire life as a writer was the year I mainly supported

myself, 1974-75, during my fifth and final year of living

in Paris, by writing capsule film reviews for a monthly

magazine in English called Oui — a joint publishing

effort of Hugh Hefner in Chicago and Daniel Fillipachi

(the publisher of Lui and, for a long stretch in the 1960s,

Cahiers du Cinéma) in Paris. At a time when I was struggling

to make ends meet -– my inheritance money having run

out, and my other freelance jobs being few and far

between -– my life was virtually saved by Terry Curtis Fox,

a Chicago-based associate editor of Oui, who engaged

me to write reviews for the magazine on a regular basis.

If memory serves, this paid $50 a review (a fortune

at the time), and I could pretty much select which films

I wrote about as long as the two-page section of the magazine

called “Prevue” could meet its monthly “tits and ass”

quotient with its illustrations, which the magazine gathered

on its own. So I wound up writing about the latest films of

Jacques Rivette, Robert Bresson, Carmelo Bene, Maurice

Pialat, Alain Resnais, and everything else I could find that

interested me, usually averaging two or three reviews per

issue, starting off with the latest films of Alain Robbe-

Grillet and Marco Ferreri in their May 1974 issue.

Another eventual contributor to this section,

interestingly enough, was the late Paul Willemen,

a film theorist and teacher whom I subsequently

met in London after I moved there to work for the British

Film Institute in 1975, where he was also working at the

time. Although I could have continued writing for Oui

then in other capacities after I went to work for Monthly

Film Bulletin and Sight and Sound (a job that I held

until early 1977, when I moved back to the U.S.), I opted

out of this work once it was no longer a financial necessity.

Here are the first two capsules I wrote for Oui,

published in their May 1974 issue.— J.R.

Glissements Progressifs du Plaisir. Practically speaking, it’s as

difficult to give a synopsis of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Glissements

Progressifs du Plaisir as it is to translate the title (Progressive

Shifts of Pleasure is a rough approximation). A beautiful woman

(Olga Georges-Picot) who has been brutally murdered with a pair of

scissors is found tied naked to a bed; the only suspect, a younger girl

found on the scene of the crime (Anicée Alvina),is kept in a prison

run by nuns and questioned by a judge (Michael Lonsdale), a pastor

(Jean Martin), and a female lawyer (Georges-Picot again).

A mystery plot? Yes and no. For Robbe-Grillet, it’s a way of

continuing to explore the archetypal images of erotic fantasy

that figured in his last two novels (La Maison de Rendezvous

and Project for a Revolution in New York). The fantasy has

been expanded here to include lesbians, medieval tortures, eggs,

vampirism, necrophilia, and an inordinate amount of red paint.

The idea of evil overtaking the murder investigation yields

multiple and contradictory answers, a musical ordering of

indecent possibilities. Key objects –- a blue shoe and a broken

wine bottle — keep reappearing in different contexts and go

through progressive kaleidoscopic shifts of meaning. The

luscious bodies of Georges-Picot and Alvina are shown

throughout to best advantage, and Jean-Louis Trintignant

puts in an uncredited appearance, parodying a police

inspector. — JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

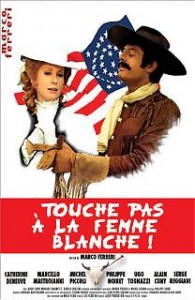

Don’t Touch the White Woman. Last time around,

Marco Ferreri’s idea for a serious comedy was to shuttle

four bored Parisians (Marcello Mastroianni, Michel

Piccoli, Ugo Tognazzi, and Philippe Noiret) off to a

country estate and watch them eat and screw

themselves to death – a premise yielding The Grande

Bouffe, one of the more intriguing morsels in last year’s

French movie fare. The sensational notion of Ferreri’s

latest, Don’t Touch the White Woman, is to set an

honest-to-God Western in the ruins of Les Halles, the

wholesale food market, which Zola called “the belly of

Paris” and which was banished to the suburbs a few

years ago.

Ferreri replaces that demolished culinary circus with all the ingredients

needed for a grand-scale horse opera: the same male leads as The

Grande Bouffe, and no less a white woman than Catherine Deneuve,

plus all the open spaces and horses that a European Western freak

could ask for. The result is slightly surreal, satirically aimed slapstick,

with the Forces of American Imperialism battling the Combined

Resources of the Third World. Mastroianni, as General Custer, slaps

his gloves and stamps his boot in deference to Puritanism and a

picture of Richard Nixon; Piccoli, deftly lampooning an American

accent as Buffalo Bill, recounts past exploits in a local bar; a host of

“Indians” -– mainly Chileans, Colombians, Vietnamese, and Ugo

Tognazzi – plot their strategies before the final massacre. But

Ferreri’s own strategy is to take off from this semiallegory into a

relaxed appreciation of sheer buffoonery, turning various locations

(including Notre Dame) into facets of his private sandbox and

appearing himself as an interested reporter. –- J.R.