Written for the StudioCanal Blu-Ray of The Trial in the Spring of 2012. — J.R.

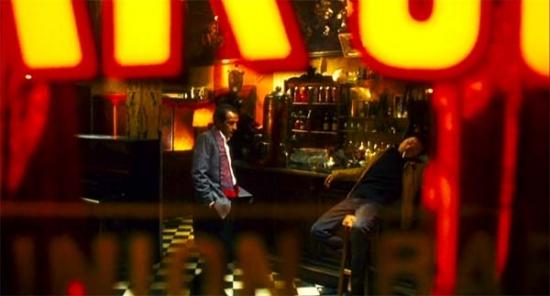

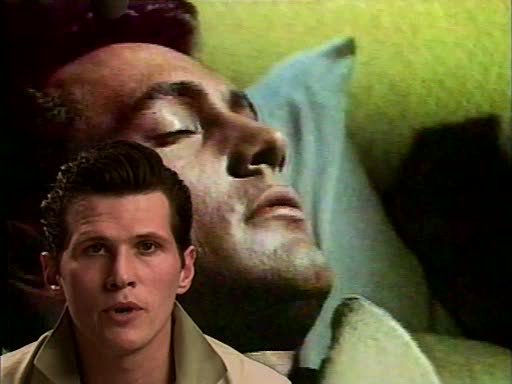

‘What made it possible for me to make the picture,’ Orson Welles told Peter Bogdanovich of his most troubling film, ‘is that I’ve had recurring nightmares of guilt all my life: I’m in prison and I don’t know why –- going to be tried and I don’t know why. It’s very personal for me. A very personal expression, and it’s not all true that I’m off in some foreign world that has no application to myself; it’s the most autobiographical movie that I’ve ever made, the only one that’s really close to me. And just because it doesn’t speak in a Middle Western accent doesn’t mean a damn thing. It’s much closer to my own feelings about everything than any other picture I’ve ever made.’

To anchor these feelings in one part of Welles’ life, he was 15 when his alcoholic father died of heart and kidney failure, and Welles admitted to his friend and biographer Barbara Leaming that he always felt responsible for that death. He’d followed the advice of his surrogate parents, Roger and Hortense Hill, in refusing to see Richard Welles until he sobered up, and ‘that was the last I ever saw of him….I’ve Read more