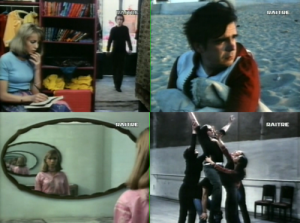

Written for Chantal Akerman: Four Films, a DVD box set released by Icarus Films on March 29, 2016. — J.R.

“When you try to show reality in cinema, most of the time it’s totally false. But when you show what’s going on in people’s minds that’s very cinematic.”

Chantal Akerman

If I had to describe the art of Chantal Akerman (1950-2015) in a single word, I think I’d opt for “composition”. This is a term that needs to be understood in its plastic as well as its musical meanings: a visual object that has to be framed in space, a musical object that has to be composed in time. And if we factor in the implied definitions offered above by Akerman regarding what’s reality and what’s cinematic, what’s going on in people’s minds and what’s going on in front of a camera and microphone, then we have to acknowledge that what she chooses to compose represents a kind of uneasy truce between all four elements (or five elements, if we regard sound and image as separate). How much she and we privilege mind over matter and cinema over reality — or vice versa — has a lot of bearing on what’s derived from the encounter. Read more