From The Movie No. 71, 1981. — J.R.

From Psycho and Spartacus (both 1960) to The Wild Bunch and Easy Rider (both 1969), the Sixties might be regarded as the period when screen violence gained a new aesthetic self-consciousness and something approaching academic respectability, at least in the public mind. To put it somewhat differently, the contemporary spectator of 1960, shocked by the brutal shower murder of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) in Psycho as an event — without observing that it was a composite film effect created by several dozen rapidly cut shots –- would have been much likelier to notice, in 1969, the use of slow motion in the depiction of several dozen violent deaths in The Wild Bunch.

The key film document of the decade, endlessly scrutinized and discussed, was not an entertainment feature at all, but the record of an amateur film-maker named Abe Zapruder of the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963; the close analysis to which this short length of film was subjected was characteristic of a changing attitude towards the medium as a whole.

In the Sixties many established cultural, social, and political values were radically thrown into question, at the same time that the media -– including television and pop music as well as cinema — were becoming closely examined in their own right. (The late Marshall McLuhan’s book Understanding Media, published in 1964, was widely regarded as a seminal text.) These two phenomena converged to create a different conception of what violence was, both as a method and as a subject.

Alfred Hitchcock, who always kept a close eye on fashion, might be considered as one barometer of that change. In Psycho and The Birds (1963) he approached the intricate problem of how to create the impression of violence in the spectator through technique and technology, from fast editing to detailed special effects. Yet by the time he made Torn Curtain (1966), a spy thriller, he was implicitly criticizing the technological fantasy engendered by such James Bond films as Dr. No (1962), From Russia With Love (1963), and Goldfinger (1964), whereby a villain could be despatched virtually with the tool flick of a switch or push of a button. Hitchcock made this point by depicting the killing of a heavy as protracted, messy, and extremely difficult –- not the sort of thing that suave 007 normally had to contend with.

The unusually long, drawn-out deaths in The Wild Bunch, on the other hand, were defended by the director Sam Peckinpah as a cathartic strategy: “‘to make violence so repulsive as to turn people against it,” was the way he expressed it in a trade journal. Other filmmakers argued, quite simply, that a liberal display of violence was merely what their stories and their subject-matter demanded — most notably, in war films such as Samuel Fuller’s Merrill’s Marauders (1962), Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967) and John Wayne’s The Green Berets (1968), and in such critiques of the genre as Jean-Luc Godard’s Les Carabiniers (1963) and Peter Watkins’ television film Culloden (shown by the BBC in 1964).

“Get up, you scum-sucking pig.” So the gun slinger played by Marlon Brando savagely challenged another tough character in One Eyed Jacks (1961). In the same year, gangs of juvenile delinquents fought each other in pitched battles (‘rumbles’) to the music of Leonard Bernstein in West Side Story, and a pool-hall hustler (Paul Newman) had his thumbs deliberately broken by rivals in The Hustler. But it would obviously be wrong to assign the Sixties any sort of monopoly in making violence look particularly glamorous, photogenic or graphic.

Yet the Sixties saw the introduction of the ‘spaghetti’ Western as well as the James Bond thriller; this suggests that the overall sense of violence possessing an aesthetic of its own was an increasingly international phenomenon, in which cultural cross-influences played a decisive part. This was no less true of the comic mishaps of Peter Sellers as inspector Jacques Clouseau in The Pink Panther (1963) and A Shot in the Dark (1964) -– both Hollywood comedies set on the Continent — and the violent, hallucinatory nightmares of European art films as diverse as The Trial (1962), Repulsion (1965), Blow-Up (1966), Weekend (1967), and Performance (1970).

All these films highlighted the cross-breeding of American and European elements in a number of ways. Spaghetti Westerns, for instance — spearheaded by a succession of hits starring Americans Clint Eastwood or Charles Bronson and directed by the Italian Sergio Leone, with music by the no less Italian Ennio Morricone — revitalized familiar American myths with Catholic symbolism, operatic intensity, and a heavy emphasis on ritual, in films such as A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Later, this became intertwined with still other strains to produce even stranger mixtures; for instance, El Topo (1971) was a gory Mexican surrealist variant of spaghetti Western with mystical drug-culture overtones, and an early favorite in the midnight cult circuits.

Any thorough survey of international trends in stylizing violence would have to acknowledge the crucial role played by Japanese cinema, more specifically, by the team of director Akira Kurosawa and actor Toshiro Mifune, mainly in an inspired series of action films ranging from Seven Samurai (1954) and Throne Of Blood (1957) to Yojimbo and Sanjuro (both 1961).

Indeed, several commentators have claimed. that the spaghetti Western and all its derivatives can be seen growing directly out of Yojimbo, a film with plenty of American antecedents of Its own. One American critic, Manny Farber, called it ” a bowdlerized version of Dashiell Hammett’s novel Red Harvest, with a bossless vagabond who depopulates a town of rival leaders, outlaws and fake heroes.”

Another critic, Donald Richie, compared the town in the film to ” those God-forsaken places in the middle of nowhere remembered from the films of Ford, of Sturges from Bad Day at Black Rock, or High Noon.”

No less striking was the cross-fertilization in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) between nouvelle vague impulses (such as the mixture of moods and genres). Hollywood showmanship (in Arthur Penn’s direction of Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway) and perhaps just a dash of Kurosawa (in the. slow-motion. balletic deaths, two years before The Wild Bunch). A grittier, black-and-white version of gangster lovers on the run followed in The Honeymoon Killers (1969 ) — interestingly enough, a favorite film of Francois Truffaut’s, where the poetry had a more romantic tinge. Just prior to this, Truffaut had been paying his own homages to American-style violence in Fahrenheit 451 (1966), his futuristic study of book-burning, and La Mariée était en noir (1968, The Bride Wore Black), the tale of a widow’s revenge on her husband’s killers. And if the latter film smacked of Hitchcock even down to its emotive Bernard Herrmann score. English director John Boorman’s exciting American thriller Point Blank (1967) drew upon the time-fragmented structures of nouvelle vague directors, particularly Alain Resnais. Here could also be detected a satirical offshoot of the equation of people with objects already noted in the Bond films: a violent gangster. played by Lee Marvin. in three separate scenes destructively attacks a car, a telephone, and an empty bed.

A few real-life robberies of the period seemed to have been modeled closely after those in Bonnie and Clyde, once again raising the question of how seriously screen violence could affect public behavior. To what degree should it be considered merely a reflection of already existing violence, as opposed to offering the spectator fresh inspirations and incentives? Recent studies of mass responses to violence, most of which have concentrated on television, have suggested that a great deal depends on how the audience’s identification is solicited, and what sort of characters have been established as role models. In the Sixties, the general use of the gangster as identification figure gave way to a similar use of the law enforcer. The critic Robert Warshow had said in 1954, “The two most successful creations of American movies are the gangster and the Westerner: men with guns.”

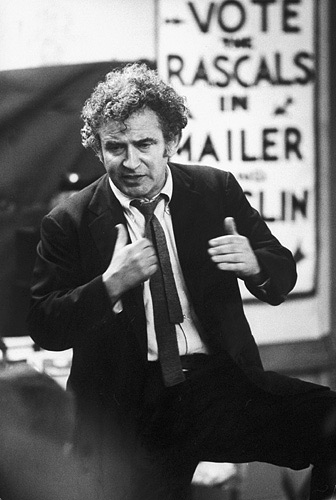

From this standpoint, there may be relatively little difference between filmmaker and novelist Norman Mailer’s playing successively a gangster in Wild 90 and a policeman in Beyond the Law (both 1968), his first two independent features.

In fact, a closer look at the cinema’s overall shift of attention away from the criminal’s viewpoint may reveal a subtle subterranean continuity. The wolf in sheep’s clothing can be no less bloodthirsty than the wolf without disguise, but his new social role and costume might be enough to exonerate him in part from guilt and society’s censure. Thus, in 1963, Underground filmmaker Kenneth Anger could explore the homoerotic potential of Hell’s Angels bikers putting on their gear in Scorpio Rising –- a sort of striptease in reverse involving chain and leather fetishes. And precisely ten years later, a fledgling director, James William Guercio, could create a comparably worshipful context while presenting the detailed dressing-up of his own hero, a likeable highway cop (Robert Blake). in Electra Glide in Blue (1973).

In a recent study of crime movies, film historian Carlos Clarens has noted that action director Don Siegel shifted his own focus in mid-career from the mad criminal in Baby Face Nelson (1957), The Lineup (1958 ) and The Killers (1964) to the policeman in Madigan, Coogan’s Bluff (both 1968), and Dirty Harry (1971). Hollywood’s reluctance (with a very few exceptions, such as The Green Berets) to deal directly with the war in Vietnam during this period created its own forms of displacement, whereby the emotional weight of the Vietnam experience became transferred to domestic law-and-order thrillers like Madigan or Bullitt (1968), which brought home the war only in the most oblique terms.

Meanwhile. as the political mood of the Sixties became increasingly polarized, violence often came to represent either society’s aggression against the young or youth’s own reprisals. in such hits as Wild in the Streets, If … (both 1968), and Easy Rider (1969). At the same time, the legacy of an equally violent past was being unearthed in certain period films — the marathon dances in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, the oppression of the Paiute Indians in Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (both 1969).

Confronted by a more recent past of senseless mass murders, In Cold Blood, Targets (both 1967) and The Boston Strangler (1968) all tried to deal with the missing motivations. In Cold Blood, adapted by Richard Brooks from Truman Capote’s non-fiction account of the arbitrary murder of a family in Kansas by two disaffected loners, added heavy doses of Freudian flashback to the original material, while The Boston Strangler focused in a quasi-documentary manner on police procedure, using a striking multi-image technique. Targets depicted a character based on the real-life University of Texas sniper and counterpointed his case with the story of an aging horror-film star (Boris Karloff), making little attempt to explain the sniper’s motives beyond implied criticism of the gun laws and of the boredom of American family life. Dryly pursuing this two-part invention about contemporary horror, the director Peter Bogdanovich followed the lead of Truffaut by turning to Hitchcock for much of his inspiration, as would other disciples in the violent Seventies.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM