From The Soho News (June 11, 1980). I’m sorry I haven’t had better luck in finding illustrations for the experimental and independent animated shorts reviewed here. But at least if you hit the first illustration, you can see it move. — J.R.

New American Animation

Film Forum, June 12-15 and l9-22

Cartoonal Knowledge

Thalia, Mondays (June through August)

Did you ever step out of a movie theater in the good old days and exclaim, “Gee, that cartoon was better than the feature”? Whether you did or not, there’s precious little chance of such a thing happening today. Thanks to some of the packaging principles that currently dominate media, short animation is often treated like a ghetto art — quarantined in its own little category and asked to stay there, mind its manners and keep a low profile, in such out-of-the-way corners as kiddie matinees and museums.

Consequently, to write about the New American Animation series at Film Forum — the last program for the season — is a bit like having to write about the Third World (another Film Forum specialty), rather than, say, simply Brazil or Algeria. And Greg Ford’s massive “Cartoonal Knowledge” series at the Thalia – encompassing 13 Mondays this summer, and billed as “probably the largest and most comprehensive cartoon festival ever mounted in a straight ‘theatrical’ context” — etches out an umbrella subject that is equally daunting to nonspecialists.

Karen Cooper, director of Film Forum, has cleverly sidestepped this problem by carefully pacing her selection of l6 shorts so that there’s a gradual crescendo and diminuendo of complexity and ambition in the overall 82 minutes, thereby letting you enter and exit her anthology as breezily as possible. All the movies were produced independently within the last three years, and none is longer than 14 minutes or briefer than two. Cumulative fatigue is what I’ve come to expect from these compilations — it will be impossible to avoid it entirely in the second program of slam-bang Tex Avery masterpieces turning up at the Thalia on June 23 (see below), where the pacing is almost invariably breakneck and relentless — but Cooper’s sense of balance and complementary diversity has effectively minimized this difficulty.

Admittedly, this victory is achieved via a certain scattershot eclecticism that promises that if one three-minute opus doesn’t grab you, the next one will. I wasn’t inordinately grabbed by the four-minute opener, Carl Surges’ At the Movies — a cutesy sort of Muppetoon featuring clay figures watching an ad for movies in a movie theater. But Howard Danelowitz’s hyperactive Inside Out kept me engrossed for 10 busy minutes. I’m told that this film is indebted to the animation of Kathy Rose; maybe so, but I was reminded of the philosophical and ontological wit of Saul Steinberg (in which, for example, the hero becomes a projector showing himself a movie), the cubist profiles of Picasso, and some of the recent free-form metamorphoses of Robert Breer. All this contributed to a fluid, wordless and dazzling nightmare that looked absolutely original to my uneducated eyes, while my ears were treated to a suggestive set of sounds including gallops and a gurgling baby.

Two other favorites of mine in the program have a distinct analytical bent. Jane Aaron’s In Plain Sight offers a profusion of animated signs plunked down in live-action places, starting with a cartoon landscape taped to the inside of a windshield in a moving car — a delightful mixture of modes recalling some of the pyrotechnics of Disney’s The Three Caballeros, though much more pantheistically and less abstractly directed. (A closer approximation to Disney would actually be the poetic handling of narrative in Jerry Lieberman’s Rollin’ Rig. done in synch to a nice trucker tune, which closes the program – a kitschy anecdote about a stork delivering babies that recalls the beginning of Dumbo.) One of the loveliest effects is of a photographed apartment house whose windows reflect passing clouds in sped-up stop-motion, with an inserted square of animated moving clouds.

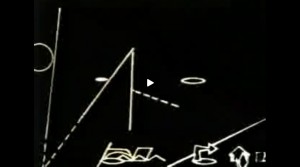

Midwesterner Paul Glabicki’s Diagram Film, the longest short in the series, uses rapid montage matching the movements of various floating shapes — like the trajectories of an animated arrow and filmed plane –- to perform diverse visual analyses. The material analyzed includes a fragment from Potemkin; and the didactic little lessons in illusionism and movement that are elegantly played out against black recall Ballet mécanique.

Midwesterner Paul Glabicki’s Diagram Film, the longest short in the series, uses rapid montage matching the movements of various floating shapes — like the trajectories of an animated arrow and filmed plane –- to perform diverse visual analyses. The material analyzed includes a fragment from Potemkin; and the didactic little lessons in illusionism and movement that are elegantly played out against black recall Ballet mécanique.

Some of the inclusions seem to suffer a bit from the sort of whimsy that infects the relatively solitary minds of writers and independent animators; I suppose these folks have every right to find their own conceits so funny after spending so much time with them, but that’s another spectator sport that counts me out. This cluster includes some of the vaudeville in Maureen Selwood’s Sempre Libera, Rufus Butler Seder’s nonanimated, brightly sophomoric and gaily paranoid Live in Fear (featuring the Paranoid Eyeball). Carter Burwell’s somewhat self-explanatory Help, I’m Being Crushed to Death by a Black Triangle, and Sally Cruikshank’s Make Me Psychic -– very ‘60s, psychedelic and San Francisco in more ways than I care to count, and somewhat studied in its goofiness.

Stampede, a rubber-stamp game composed by Ken Brown, and matched to good hoedown music by The Last Mile Ramblers, left little impression. But this fortunately cleared the way for Mary Beam’s shimmering, fascinating Whale Songs and Susan Rubin’s August 1978 (with its remarkable sense of human gesture periodically rising to the surface of the line drawings like ecstatic bubbles) — making Stampede as useful as a glass of water between courses in a meal.

By the time this reaches print, two successive programs in Cartoonal Knowledge will have already played at the Thalia, featuring Walter Lanz, Ub Iwerks and the first installments of Tex Avery and Chuck Jones shows. This means that a lot of people — including me, alas — have already missed my all-time favorite Avery cartoon Who Killed Who? — an upsetting manic blend of live-action and animation in which the photographed narrator, sitting very sedately behind his serious-looking desk, turns out to be the mysterious perpetrator of the cartoon crime), as well as an exceptionally rare 1944 Jones effort called Hell Bent for Election, which was mainly designed to get Roosevelt back in office.

By the time this reaches print, two successive programs in Cartoonal Knowledge will have already played at the Thalia, featuring Walter Lanz, Ub Iwerks and the first installments of Tex Avery and Chuck Jones shows. This means that a lot of people — including me, alas — have already missed my all-time favorite Avery cartoon Who Killed Who? — an upsetting manic blend of live-action and animation in which the photographed narrator, sitting very sedately behind his serious-looking desk, turns out to be the mysterious perpetrator of the cartoon crime), as well as an exceptionally rare 1944 Jones effort called Hell Bent for Election, which was mainly designed to get Roosevelt back in office.  Fortunately, there are still 11 Mondays to go in the series. with lots of studio animation treats in store. On June 16, a series of Fritz Freling’s Warner Brothers classics (including two Bugs Bunny Hollywood parodies and early incarnations of Tweety. Sylvester and Yosemite Sam) alternates with some silent, black-and-white Felix the Cat frolics from the ‘20s. Then, on the 23d, comes a second chapter in ‘20s s animation — Max and David Fleischer’s odd “Out of the Inkwell” series — and Part 2 in the Tex Avery Show, which includes a lot of indispensable items from his stints at both Warners and M.G.M.

Fortunately, there are still 11 Mondays to go in the series. with lots of studio animation treats in store. On June 16, a series of Fritz Freling’s Warner Brothers classics (including two Bugs Bunny Hollywood parodies and early incarnations of Tweety. Sylvester and Yosemite Sam) alternates with some silent, black-and-white Felix the Cat frolics from the ‘20s. Then, on the 23d, comes a second chapter in ‘20s s animation — Max and David Fleischer’s odd “Out of the Inkwell” series — and Part 2 in the Tex Avery Show, which includes a lot of indispensable items from his stints at both Warners and M.G.M.

According to programmer Greg Ford, Avery quit Warner Brothers and went over to M.G.M. in the early’40s because his producer, Leon Schlesinger, cut the ending of The Heckling Hare, an exceptionally frightening Bugs Bunny included in Part 2 whose horrific climax -– described at some length in Noël Burch’s Theory of Film Practice (and misremembered there as a Cat and Dog cartoon, though it is correctly placed among “structures of aggression”) -– consists of Bugs and a hunting dog named Willoughby screaming their bloody lungs out as they fall from a cliff down a bottomless chasm for what seems like forever. (Avery’s cut ending prolonged the gag by having the characters spill off yet another cliff before they landed.)

According to programmer Greg Ford, Avery quit Warner Brothers and went over to M.G.M. in the early’40s because his producer, Leon Schlesinger, cut the ending of The Heckling Hare, an exceptionally frightening Bugs Bunny included in Part 2 whose horrific climax -– described at some length in Noël Burch’s Theory of Film Practice (and misremembered there as a Cat and Dog cartoon, though it is correctly placed among “structures of aggression”) -– consists of Bugs and a hunting dog named Willoughby screaming their bloody lungs out as they fall from a cliff down a bottomless chasm for what seems like forever. (Avery’s cut ending prolonged the gag by having the characters spill off yet another cliff before they landed.)

Other definite hits on this bill (in more ways than one) include the acute sexual frenzies of Uncle Tom’s Cabana and Red Hot Riding Hood, and the brutal, brilliant anti-illusionist hijinks of Bad Luck Blackie (in which a piano, tractor. tree and bus all fall from the sky to land on the hero) and Screwball Squirrel (a character who, as Joe Adamson ungrammatically but aptly notes, is “Daffy Duck taken one step further than he absolutely has to”).

Other definite hits on this bill (in more ways than one) include the acute sexual frenzies of Uncle Tom’s Cabana and Red Hot Riding Hood, and the brutal, brilliant anti-illusionist hijinks of Bad Luck Blackie (in which a piano, tractor. tree and bus all fall from the sky to land on the hero) and Screwball Squirrel (a character who, as Joe Adamson ungrammatically but aptly notes, is “Daffy Duck taken one step further than he absolutely has to”).

I’m somewhat less partial to Avery’s more celebrated and rigidly obsessive, tall-tale Texan nightmares about size and scale, Half-Pint Pygmy and King Size Canary, but I’m willing to concede that I might have viewed them too ahistorically. Greg Ford reports that when the latter cartoon, made in 1947, was recently shown in the Soviet Union, the audience took it all as a Cold War allegory, with cat and mouse standing respectively for the U.S. and Communist blocs, each swallowing more and more quantities of Jumbo Gro in order to dwarf the other and thus literally rule the planet. The funniest thing about this reading is that it may be right.

I’m somewhat less partial to Avery’s more celebrated and rigidly obsessive, tall-tale Texan nightmares about size and scale, Half-Pint Pygmy and King Size Canary, but I’m willing to concede that I might have viewed them too ahistorically. Greg Ford reports that when the latter cartoon, made in 1947, was recently shown in the Soviet Union, the audience took it all as a Cold War allegory, with cat and mouse standing respectively for the U.S. and Communist blocs, each swallowing more and more quantities of Jumbo Gro in order to dwarf the other and thus literally rule the planet. The funniest thing about this reading is that it may be right.