From the Jewish Daily Forward, January 31, 2013. — J.R.

I’ve seen only two features written and directed by Michael Roemer — Nothing But a Man (1964) and The Plot Against Harry (made between 1966 and 1968, but released only in 1989). Either of these suffice to make him a major American filmmaker. And two other Roemer scripts I’ve read — one of which he managed to film (Pilgrim, Farewell, 1982), the other of which he hasn’t (Stone My Heart — undated, but apparently from the late 60s and/or early 70s) — show equivalent amounts of conviction, originality, density, and courage. But there’s a fair chance that you’ve never heard of him. And I think one of the reasons why could be that he’s a man who knows too much.

What do I mean by this? Partly that these films are politically incorrect (meaning that they all grapple with life while posing diverse challenges to people who think mainly in established and unexamined political and ethnic categories) and partly that in filmmaking we often confuse advertising and hustling with other kinds of talent — most obviously when it comes to the Oscars, but also when it comes to how we categorize and package various achievements. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Spring 1980). -– J.R.

Now that criticism and advertising are becoming harder and harder to separate in American film culture, the notion of any genuinely spontaneous movie cult becomes automatically suspect. It implies something quite counter to the megacinema of Cimino, Coppola and Spielberg — a cinema that can confidently write its own reviews (and reviewers) if it wants to, working with the foreknowledge of a guaranteed media-saturation coverage that will automatically recruit and program most of its audience, and which dictates a central part of its meaning in advance.

For a long time in the U.S. (as elsewhere), certain specialized minority interests that get shoved off the screens by the box-office bullies have been taking refuge in midnight screenings, most of them traditionally held at weekends. But what seems truly unprecedented about the elaborate cult in the U.S. that has developed around Friday and Saturday midnight screenings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, over the past three and a half years, is the degree to which a film has been appropriated by its youthful audience. Indeed, it might even be possible to argue that this audience, rather than allow itself to be used as an empty vessel to be filled with a filmmaker’s grand mythic meanings, has been learning how to use a film chiefly as a means of communicating with itself. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Summer 1975). I think I probably did a better job with The Godfather 33 years later, when I wrote something about it for Filmkrant. — J.R.

The Godfather Part II

‘I believe in America,’ declares an undertaker in portentous close-up at the start of The Godfather, appealing to Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) to dispatch an act of vengeance on his behalf. The sequel begins and ends with close-ups of Michael (Al Pacino), Vito’s youngest son and successor: in the first his hand is being kissed off-screen by yet another supplicant; in the last he sits alone biting his knuckle, with his wedding ring clearly in evidence — an apt symbol of his solitary dominion, with the Corleone family virtually destroyed so that its hollow emblems and relics might be preserved. The most obvious achievement of The Godfather Part II (CIC) over its predecessor can be seen in the quiet authority of this framing device, which tells us everything we need to know about the fate of the Corleones without recourse to rhetorical hectoring; its most obvious limitation is that it essentially tells us nothing new.

Perhaps more than anyone else in Hollywood, Francis Ford Coppola epitomizes the man in the middle. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 512). — J.R.

Buffalo Bill and the lndians, or

Sitting Bull’s History Lesson

U.S.A., 1976

Director : Robert Altman

Cert-A. dist-EMI. p.c–Dino De Laurentiis Corporation/Lion’s Gate Films/Talent Associates-Norton Simon. exec..-p-David Susskind. p– Robert Aitman. assoc. p–Robert Eggenweiler, Scott Bushnell, Jac Cashin. p. exec—Tommy Thompson. asst. d–Tommy Thompson,Rob Lockwood. sc–Alan Rudolph, Robert Altman. Suggested by the play Indians by Arthur Kopit. ph–Paul Lohmann. Panavision. col–Deluxe General.ed-Peter Appleton, Dennis Hill. p. designer–Tony Masters. a.d–Jack Maxsted. set dec–Dennis J. Parrish, Graham Sumner. scenic artist–Rusty Cox. sp. effects–Joe Zomar, Logan Frazee, Bill Zomar, Terry Frazee, John Thomas. M–Richard Baskin. cost–Anthony Powell. make-up–Monty Westmore. titles-Dan Perri. sd. ed–William Sawyer,_Richard Oswald. sd. rec–Jim Webb, Chris McLaughlin. sd. re-rec–Richard Portman. research–Maysie Hoy. wrangler–John Scott. l.p–Paul Newman (Buffalo Bill), Joel Grey (Nate Salsbury), Burt Lancaster (Ned Buntline). Kevin McCarthy (Major John Burke), Harvey Keitel (Ed Goodman), Allan Nicholls (Printiss Ingraham), Geraldine Chaplin (Annie Oakley). John Considine (Frank Butler), Robert Doqui (Osborne Dart), Mike Kaplan (Jules Keen), Bert Remsen (Crutch), Bonnie Leaders (Margaret), Noelle Rogers (Lucille Du Charmes), Evelyn Lear (Nina Cavalini), Denver Pyle (McLaughlin),Frank Kaquitts (Sitting Bull), Will Sampson (William Halsey), Ken Krossa (Johnny Baker), Fred N. Larsen (Buck Taylor), Jerri Duce and Joy Duce (Trick Riders), Alex Green and Gary MacKenzie (Mexican Whip and Fast Draw Act), Humphrey Gratz (Old Soldier), Pat McCormick (Grover Cleveland), Shelley Duvall (Frances Folsom). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 14, 1995). I’m not sure why, but this is one of the most popular posts on this site. — J.R.

Priest

**

Directed by Antonia Bird

Written by Jimmy McGovern

With Linus Roache, Tom Wilkinson, Cathy Tyson, Robert Carlyle, James Ellis, Lesley Sharp, Robert Pugh, and Christine Tremarco.

A friend of mine who hasn’t even seen Priest calls it “post-Oprah,” and it’s easy to see what he means — in terms of pacing as well as subject matter. Its first incarnation was as a 200-page script by Jimmy McGovern for a four-part BBC miniseries, but he shaved it to 65 pages when the BBC decided to make it a feature. When it went out to festivals last year (where it won numerous awards), director Antonia Bird’s cut was 109 minutes; since then it’s been trimmed by 8 minutes, apparently to make it eligible for an R rating: its distributor, Miramax, now under the control of the Disney studio, isn’t allowed to release any NC-17 pictures. I haven’t seen the longer version, but it’s likely that these successive abridgments have both produced the taut narrative that’s central to the movie’s powerful impact as entertainment and limited it as art and as a piece of sustained thought. Read more

From Film Quarterly, Winter 1990–91.-– J.R.

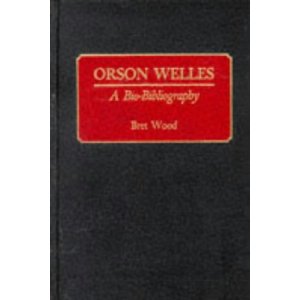

Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography, by Bret Wood (Westport, CT: Greene Press, 1990).

Issued without dust wrappers and priced beyond the range of most individuals, this 364-page book is clearly intended for libraries, and not likely to get much attention outside of specialized publications. But as a multifaceted research tool for anyone investigating the career of Orson Welles it is a veritable godsend — more valuable in some ways than any of the Welles biographies published so far.

Not counting introduction, endnotes, index, a skeletal Welles chronology, an invaluable section devoted to special sources, and ten well-chosen illustrations, the book is divided into eight sections: Biographical Sketch, Theatre Credits, Radio Credits, Film Credits, Welles as Author, Discography (a brief section that regrettably excludes commercial releases of radio broadcasts), Books and Monographs on Welles, and Articles on Welles. Probably the most valuable of these sections in terms of fresh material are the two longest, Radio Credits (74 pages) and Film Credits (120 pages), containing not only listings but, in many cases, descriptive and critical annotations. (The length of the film section can largely be accounted for by the fact that Wood is as attentive to unrealized projects as he is to finished works.) Read more

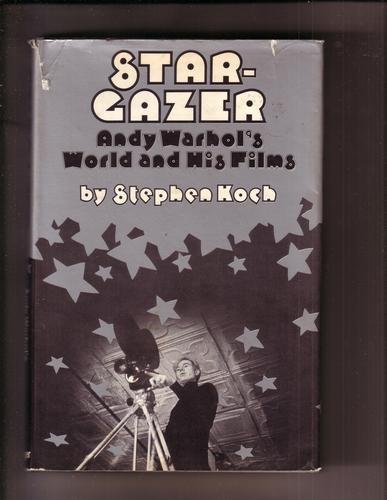

From Film Quarterly (Spring 1974). I wrote this review while I was living in Paris, which made acquiring a review copy especially difficult. (I grimly recall even getting into something resembling a fistfight with the French distributor of the book, who didn’t want to give me one and blew a fuse when I insisted, even though I had an assignment.) Stephen Koch, whom I knew from my previous stint as a graduate student at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, was a friend at the time, as was Annette Michelson, who commissioned the book for Praeger. My second-hand assessment of **** (Four Stars) came from another friend, Lorenzo Mans, who saw the entire film and reviewed it for the Village Voice, though I had attended a New York screening of Blue Movie, when it went by the title Fuck. -– J.R.

STAR-GAZER:

ANDY WARHOL’S WORLD AND HIS FILMS

BY Stephen Koch. New York: Praeger. $8.95.

Books about filmmakers that do something more than regurgitate filmographies and sketch career summaries are not exactly plentiful these days, and for this reason alone Stargazer is worthy of serious attention. What it attempts is not a mere pigeon-holing of Warhol’s films but a complex assessment of his persona and its accompanying strategies — in, through and beyond these films — as they flourished in the sixties. Read more

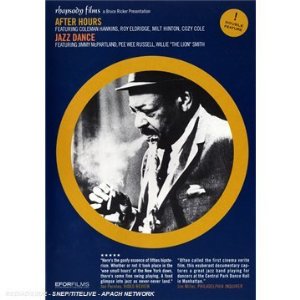

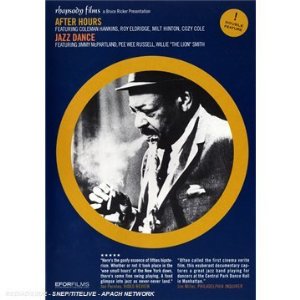

From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 510). I’ve made a couple of corrections and added several basic credits, visible now at the end of my VHS copy but not accessible to me back in 1976. (I should add that the pitches made by the coproducer to potential sponsors aren’t on the VHS version.) Thanks to Ehsan Khoshbakht for some help with the illustrations.–- J.R.

After Hours

U.S.A., 1961

Director: Shepard Traube

Dist–TCB. p–Shepard Traube, Arthur Small. sc–Arthur Small. p. sup– George Goodman. ph–Arthur Ornitz. ed–Morton Fallick. sd–Robert Lessner, Frank J. Gaily. m/songs—“Lover Man” by Jimmy Davis, Roger “Ram” Ramirez, Jimmy Sherman, “Sunday” by Chester Conn, Ned Miller, Bennie Krueger, Jule Styne, “Just You, Just Me” by Jesse Greer, Raymond Klages, “Taking a Chance on Love” by Vernon Duke, John Latouche, Ted Fetter, performed by Coleman Hawkins (tenor sax), Roy Eldridge (trumpet, vocals), Johnny Guarnieri (piano), Barry Galbraith (guitar), Milt Hinton (bass), Cozy Cole (drums), Carol Stevens (vocals). l.p— Meredith Gaynes (Cigarette Girl), Albert Minns (Head Waiter), Leon James (Doorman), Richard Blackmarr (Bartender). narrator— William B. Williams. 967 ft. 27 mins. (16 mm.).

A TV pilot which failed to attract sponsors, After Hours carries all the poignance of a noble lost cause. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1975, Vol. 42, No. 500. — J.R.

W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings

U.S.A..1975

Director: John G. Avildsen

Cert—A. dist–Fox-Rank. p.c–20th Century-Fox. exec. p–Steve

Shagan. p–Stanley S. Canter. p. manager–William C. Davidson. asst. d

–Ric Rondell, Jerry Grandey. sc–Thomas Rickman. ph–Jim Crabe.

col–TVC; prints by DeLuxe. ed–Richard Halsey, Robbe Roberts. a.d—

Larry Paull. set dec–JimBerkey. sp. effects–Milt Rice. m–Dave Grusin.

songs–“Hound Dog” by Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller, sung by Elvis

Presley; “Goodnight, Sweetheart, Goodnight” by Calvin Carter, James

Hudson; “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry; “Bye Bye Love” by

Felice Bryant, Boudleaux Bryant; “I’m Walkin’” by Antoine “Fats”

Domino, Dave Bartholomew; “Blue Suede Shoes” by Carl Lee Perkins;

“Mama Was a Convict” by Tom Rickman, Tim Mclntire; “A Friend” by

Jerry Reed; “Dirty Car Blues” (traditional), performed by Furry Lewis.

cost–Dick LaMotte. titles–PacificTitle. sd. rec–Bud Alper. sd. re-rec—

Don Bassman. stunt co-ordinator–Hal Needham. l.p–Bert Reynolds

(W.W. Read more

What an onslaught of deaths that week in late March, 2021: Morris Dickstein, Larry McMurtry, Bertrand Tavernier, George Segal….The latter prompted this reposting. From Stop Smiling No. 35 (its gambling issue, guest edited by Annie Nocenti), June 2008. — J.R.

“Trusting to luck means listening to voices,” Jean-Luc Godard reportedly said at some point in the mid-1960s. This has always struck me as being one of his more obscure aphorisms, and one that even seems to border on the mystical. Yet the minute one starts to apply it to Robert Altman’s California Split, released in 1974 —- a free-form comedy about the friendship that develops and then plays itself out between two compulsive gamblers, Charlie (Elliott Gould) and Bill (George Segal), and the first movie ever to use an eight-track mixer — it starts to make some weird kind of sense.

What’s an eight-track mixer? According to the maestro of overlapping dialogue himself, speaking in David Thompson’s Altman on Altman (Faber and Faber, 2006), this is a system known as Lion’s Gate 8-Tracks developed by Jim Webb, and it grew directly out of Altman’s ongoing efforts to make on-screen dialogue sound more real. Sound mixers would frequently complain that some actors wouldn’t speak loudly enough and Altman would counter that this was a recording problem, not a performance problem involving the actors’ deliveries. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 493). –- J.R.

Wavelength

Canada, 1967

Director: Michael Snow

Dist–London Film-makers Co–op. conceived and executed by—Michael Snow. In color. ed–Michael Snow. song—“Strawberry Fields Forever” by John Lennon, Paul McCartney. performed by—The Beatles. sd–_Michael Snow. l.p–Hollis Frampton (Man Who Dies), Amy Taubin (Woman on Phone). 1,538 ft. 45 min. (16 mm.).

A camera zooms across the length of an 80-foot urban loft, beginning from a distance approximating the camera’s fixed. Position — where most of the room is visible — and proceeding towards the four vertical double-windows, three intervening sections of wall space, desk, chairs and radiator on the opposite side, accompanied on the soundtrack by a sine wave gradually progressing from its lowest note (50 cycles per second) to its highest (12,000 cycles per second). The zoom mainly proceeds through a series of periodic jerks, between occasional shot changes, while the images pass through a variety of colored filters, film stocks, and qualities and degrees of processing (positive and negative)and light exposure (controlled by the camera, four light fixtures on the ceiling, and the time of day). It is interrupted four times by a visible human event, and during each of these the sine wave is overlaid with synchronized sound: (1) A woman and two men enter the room, and the former directs the latter to set a bookshelf down against the wall on screen left; all three leave. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin , September 1976, Vol. 43, No. 512. — J.R.

Director: Michael Snow

Canada, 1969

Dist–London Film-makers Co-op /Cinegate. conceived and executed by— Michael Snow. In colour. ed–Michael Snow. sd–Darvin Studio. with— Allan Kaprow, Emmett Williams, Max Neuhaus, Terri Marsala, Donna Aughey, Joyce Wieland, Louis Commitzer, George Murphy, Dr. Gordon, Liba Bayrak, Anne Scotty, Nancy Graves, Richard Serra, John Giorno, Paul Iden, Alison Knowles, Jud Yalkut, Susan Ay-O, Mac, students in the HEP program at Farleigh Dickinson University. 1,872 ft. 52 mins.

(16 mm.)

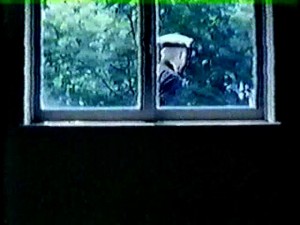

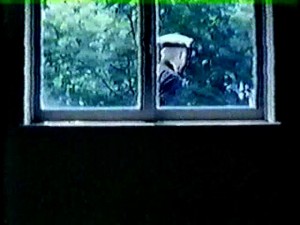

Alternative title—Back and Forth

The camera pans back and forth across an outside wall of a classroom while a man crosses part of the field. The pan resumes inside the classroom in a fixed trajectory, revealing an asymmetrical area including part of a blackboard and a door on a far wall, two pairs of windows on the wall closer to the camera, and desks in front of the blackboard; trees, building and occasionally passing vehicles are partially visible through the doors and windows.

Throughout, one hears the sound of the camera’s mechanisms, including a loud report at the beginning and end of each pan. Various cuts emphasise that certain parts of individual pans, or entire pans, or a number in series, were filmed at different times. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 22, 1994). — J.R.

** THE LION KING

(Worth seeing)

Directed by Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff

Written by Irene Mecchi, Jonathan Roberts, and Linda Woolverton

With the voices of Matthew Broderick, James Earl Jones, Jeremy Irons, Rowan Atkinson, Moira Kelly, Jim Cummings, Whoopi Goldberg, and Cheech Marin.

Though it’s somewhat less entertaining than The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin, The Lion King marks a welcome and fascinating shift in the Disney animated feature. It may be just a coincidence, but Disney’s new live-action Angels in the Outfield, a multicultural remake of a 1951 baseball fantasy, marks the same kind of racial and ethnic reorientation. I’d like to think that the widespread (and justifiable) objections raised by Middle Eastern groups to the xenophobic stereotypes in Aladdin have finally led to some rethinking by Disney executives about how to handle such ethnic material. If my hunch is correct, these changes represent not so much a kowtowing to political correctness as a more accurate reckoning of Disney’s stateside and international audience.

The issue isn’t exactly reality versus fantasy, because all Disney pictures are fantasies. In real life a white orphan isn’t likely to be adopted by a black man even if the white orphan’s best friend is a black orphan who comes along with the bargain (as in Angels in the Outfield). Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1976, Vol. 43, No. 504. — J.R.

Faustrecht der Freiheit (Fox)

West Germany, 1975

Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Ce r t–X. dist–Cinegate. p.c–Tango-Film. p–Rainer Werner Fassbinder. p. manager–Christian Hohoff. asst. d–Irm Hermann. sc—Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Christian Hohoff. ph–Mictrael Ballhaus. col–Eastman Colour. ed–Thea Eymèsz. a.d–Kurt Raab. m–Peer Raben. songs–“One Night” by Pearl King, Dave Bartholomew, performed by Elvis Presley; “Bird on the Wire” by and performed by Leonard Cohen. l.p–Rainer Werner Fassbinder (“Fox” Franz Biberkopf), Peter Chatel (Eugen Theiss), Karl- Heinz Böhm (Max), Harry Bär (Philip), Adrian Hoven (Eugen’s Father), Ulla Jacobsen (Eugen’s Mother), Christiane Maybach (Hedwig), Peter Kern (Florist “Fatty” Schmidt), Hans Zandler (Man in Bar), Kurt Raab (Barman Springer),Irm Hermann (Mlle. Chérie de Paris), Barbara Valentin (Max’s Wife), Walter Sedlmayr (Car Dealer), Ingrid Caven (Singer in Bar), (El Hedi Ben Salem (Moroccan), Brigitte Mira (Shopkeeper),Bruce Low (Soldier), Ursula Strätz, Elma Karlowa, Evelyn Künneke, Marquart Bohm, Liselone Eder, Klaus Löwitsch.

11,077 ft. 123 mins. Subtitles.

“Fox” Franz Biberkopf, a carnival sideshow performer, loses his job and his lover Klaus (who runs the show) when the latter is arrested. Read more

There’s a particular Parisian tradition that seems peculiar to French aesthetics involving a certain license to behave like a depraved lunatic and receive approval, endorsement, and other cultural rewards in return for this boorishness.(Many years back I tried writing about this subject, in a long review of My Life and Times with Antonin Artaud.) I suppose one very bourgeois way of describing this tendency would be to call it the aesthetics of self-indulgence combined with a gift for self-promotion, and though I don’t know French literature well enough to determine what poets might have established this trend (apart from such relatively modern figures as Baudelaire and Rimbaud), there’s no question that Jean Cocteau set down many of the terms and conditions of this tradition in cinema, along with the visiting Spaniards Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali — including, perhaps, a special talent for hustling up various forms of patronage.

Even though not all artists with these characteristics are French, much less Parisian, it could perhaps be argued that those who are commonly celebrated for these traits are typically appreciated either by French critics (Nicole Brenez writing about Abel Ferrara) or Francophile critics (such as Adrian Martin writing about Philippe Grandrieux, among many others). Read more