From the Jewish Daily Forward, January 31, 2013. — J.R.

I’ve seen only two features written and directed by Michael Roemer — Nothing But a Man (1964) and The Plot Against Harry (made between 1966 and 1968, but released only in 1989). Either of these suffice to make him a major American filmmaker. And two other Roemer scripts I’ve read — one of which he managed to film (Pilgrim, Farewell, 1982), the other of which he hasn’t (Stone My Heart — undated, but apparently from the late 60s and/or early 70s) — show equivalent amounts of conviction, originality, density, and courage. But there’s a fair chance that you’ve never heard of him. And I think one of the reasons why could be that he’s a man who knows too much.

What do I mean by this? Partly that these films are politically incorrect (meaning that they all grapple with life while posing diverse challenges to people who think mainly in established and unexamined political and ethnic categories) and partly that in filmmaking we often confuse advertising and hustling with other kinds of talent — most obviously when it comes to the Oscars, but also when it comes to how we categorize and package various achievements.

Some filmmakers tell us more than we know how to process and cope with, unlike the Hollywood fantasies that, by design, are much easier to consume. And apart from being a bit of a pessimist, Roemer is a fanatical believer in research.By his own account, he fell in love with stories at a very early age, as a means of escape, but a feeling that he had to believe in them was no less pronounced. For Nothing But a Man, he traveled extensively through the Deep South during the height of the civil rights movement, staying with black families; and for The Plot Against Harry, a comedy about a Jewish gangster based in the Bronx, he spent a year working as a caterer’s assistant at bar mitzvahs and Jewish weddings and following an attorney around Manhattan law courts to investigate the numbers racket.

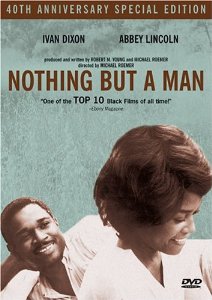

Nothing But a Man is politically incorrect because it’s a film about the lives of American black people produced, written, directed, and photographed by white men, most of them Jewish — principally, Roemer and his longtime friend and former college classmate Robert M. Young (who went on to garner more of a reputation than Roemer, through such films of his own as Alambrista!, One Trick Pony, and Dominick and Eugene). I first saw it in 1964, and I’ve regarded it ever since as one of the first authentic films made about American blacks in the South (even though the film was shot exclusively in New Jersey). I grew up in Alabama, where the film’s action is set, and even though I’ve had a lifelong aversion to films that misrepresent the South and mangle Southern accents — and despite the fact that, as Roemer points out, all the white characters in the film have Southern accents and all the black characters don’t — the overall level of accurate observation is such that I wasn’t surprised to read that it was Malcolm X’s favorite film. And The Plot Against Harry seems no less authentic.

Roemer’s knowing too much must have started at an early age. He grew up as a Jew in Berlin, where he spent much of the first eleven years of his life (1928-1938) dodging Nazis, until, half a year after the Kristallnacht, he and his sister were packed onto a train bound for England with 300 other Jewish children, and spent the war at a boarding school in Kent. By his own account, he fell in love with stories at a very early age, but a feeling that he had to believe in the stories in order to understand them was no less pronounced, and this led him into research. Shortly before he turned 18, he and his sister left on a convoy of armed ships for New York, where they were greeted by their mother, whom they hadn’t seen for six years.

Attending Harvard on a scholarship in 1945, Roemer majored in English, edited a Zionist journal, and, before graduating with honors, made a film there entitled A Touch of the Times for $2300 that was probably the first independent feature ever produced at an American university. In an essay in the first volume of his Film Stories: Screenplays as Story (The Scarecrow Press, 2001), a collection of his screenplays (including Nothing But a Man, The Plot Against Harry, Stone My Heart, and Pilgrim, Farewell), he mordantly reports that it was “intended as social satire” and, thanks to a premiere “at a Harvard Square theater on the evening of the Princeton game” that paid back the film’s negative cost,” “from a financial point of view, it remains my most successful film.” Life magazine even published a three-page story about it, but characteristically, it doesn’t appear to have been screened many times since 1949.

Many other false starts to Roemer’s career as a filmmaker followed — and here, I think, is where him knowing too much starts to become pertinent. After several unsuccessful writing assignments, he notes, “I realized that my problem wasn’t incompetence, but an inability to lend myself to a story without spending far more time exploring the facts than the assignments allowed,” which led to him spending seven years on various film crews. Then he spent four years making about a hundred educational films. In 1962, he was approached by Young to collaborate on an NBC TV documentary about poverty in a Sicilian slum, and it appears that they wound up doing such an effective job that NBC refused to broadcast it. This led to Roemer and Young deciding to produce their own next work together, which both of them would write, Young would shoot, and Roemer would direct; this eventually became Nothing But a Man.

This film was a success, but it led to a professional impasse. After Roemer and Young purchased an option on Elie Wiesel’s Dawn, a novel about the Holocaust, and accepted a documentary assignment in Israel to further explore this subject, Roemer concluded after a year of research that a fiction film on this topic was impossible. Meanwhile, having subsequently regretted that Nothing But a Man tended to neglect humor as a part of black culture, Roemer decided to make a comedy about middle-class urban Jews and money, thereby launching the research that eventually yielded The Plot Against Harry — a film that enlisted Young once again as coproducer and cinematographer.During this same period, Roemer began teaching filmmaking and screenwriting at Yale, a job that has sustained him ever since.

But he was mortified to discover that The Plot Against Harry — a tale about a Jewish gangster in the numbers racket trying and failing to go straight by buying his way into the middle-class — was deemed unreleasable. No one laughed at the screenings; apparently the black and white documentary style as well as the complicated, rather melancholy plot (which boasts over three dozen characters) confounded most comic expectations. I suspect that the subtle social satire, at once devastating and warmly forgiving, didn’t help either.

It was only two decades later, when Roemer was transferring his films to video to give to his children, and the technician he was working with started to laugh at The Plot Against Harry, that Roemer concluded he might have done something right. He remixed the sound, struck a new print, and submitted the film to both the New York and Toronto film festivals; both accepted it immediately. It went on to screen around the world, and this time people mainly laughed.

But the success plainly came too late to build any career around it. After Harry, Roemer spent “two and a half years, seven hours a day, six days a week” writing Stone My Heart, a powerful script about a brutally dysfunctional family that he’s never been able to shoot, then a script called Haunted that he was eventually able to direct for TV in 1984. His well-received TV documentary, Dying, about the lives and family relationships of three people facing death, led to another script, Pilgrim, Farewell, which he was able to shoot (again for TV) in 1982.

The common thread of all these scripts is a quintessential American theme–family dysfunction. Duff (Ivan Dixon), the hero of Nothing But a Man, was abandoned by his father (Julius Harris), and has subsequently abandoned his own son; Harry’s hapless efforts to join the middle-class are paralleled by his failure to sustain either of his marriages. Roemer has admitted being driven to make Nothing But a Man for personal rather than altruistic reasons, and the problem of having an absent father was partially his own. Maybe this is why he reportedly spent hours with Harris on each of his lines, and why more generally he is such a consummate director of actors. Abbey Lincoln in the same film and Martin Priest in both of Roemer’s early features — a racist redneck in the first, Harry in the second — are so uncommonly fine that we repeatedly forget that they’re actors. Maybe this is because Roemer is ultimately more interested in life than in movies — a classic commercial liability.