From Sight and Sound (Spring 1980). -– J.R.

Now that criticism and advertising are becoming harder and harder to separate in American film culture, the notion of any genuinely spontaneous movie cult becomes automatically suspect. It implies something quite counter to the megacinema of Cimino, Coppola and Spielberg — a cinema that can confidently write its own reviews (and reviewers) if it wants to, working with the foreknowledge of a guaranteed media-saturation coverage that will automatically recruit and program most of its audience, and which dictates a central part of its meaning in advance.

For a long time in the U.S. (as elsewhere), certain specialized minority interests that get shoved off the screens by the box-office bullies have been taking refuge in midnight screenings, most of them traditionally held at weekends. But what seems truly unprecedented about the elaborate cult in the U.S. that has developed around Friday and Saturday midnight screenings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, over the past three and a half years, is the degree to which a film has been appropriated by its youthful audience. Indeed, it might even be possible to argue that this audience, rather than allow itself to be used as an empty vessel to be filled with a filmmaker’s grand mythic meanings, has been learning how to use a film chiefly as a means of communicating with itself.

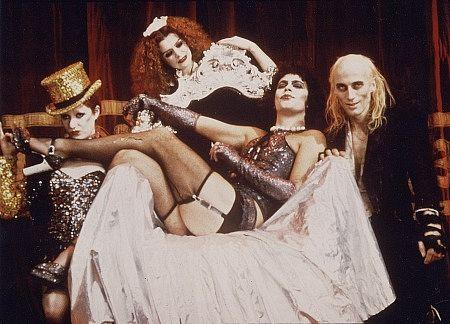

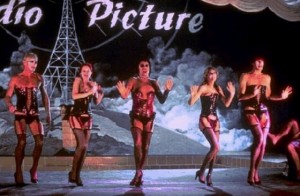

How did this initially happen? As a play, The Rocky Horror Show –– an English transsexual horror rock musical, crammed with references to American and British B-films, directed by Jim Sharman and written by Richard O’Brien, who also played the part of Riff Raff, a butler — opened at the Royal Court’s Theatre Upstairs in June 1973. It moved subsequently to the King’s Road Theatre in Chelsea, where I saw it the following summer, and is still running at the Comedy. An energetic theater piece, it was enlivened especially by a good score and an exciting performance by Tim Curry as Frank N Furter. The latter character is the transvestite leader of an annual convention, held on Earth, of aliens from the distant planet Transylvania. He plays host and (sexual) Mephistopheles to Brad and Janet, an innocent American couple who turn up at his mansion when their car breaks down in a rainstorm.

The original play derives to some degree from a historical meditation on some aspects of pop culture, even though it confuses and overlaps different strains in that history with what seems to be anachronistic abandon and campy indifference.(The opening song, ‘Science Fiction Double Feature’, cites pell-mell Michael Rennie in The Day the Earth Stood Still, Flash Gordon, Claude Rains as The Invisible Man, Fay Wray in King Kong, Leo G. Carroll in Tarantula, Dana Andrews in Night of the Demon.) During the first year or so of the play’s run, it was quite apparent that it had personal and political importance for many of my English friends who were roughly the same age (early thirties), women in particular. It was as if some of the more liberating aspects of counter-culture and ‘swinging London’, rock and cinephilia, had become attached to a specific dream of sexual liberation –- adream rather than a more explicit invitation to action, because the overall emotional tone of the play, despite the overt violence and kinkiness, exuded tenderness, shyness and innocence of a specifically English variety.

In different terms, one could say that the coziness of the Beatles and the danger of the Rolling Stones were equally present (at least in their potentiality) in the Rocky Horror myth, and were even made to seem compatible by the fact that, like so much English culture, this myth is structured round the very notion of the familiar and reliable, the tried and true. So there was nothing deeply threatening about the play because there was nothing essentially new in it, merely a conscious reshuffling of clichés that allowed one to see the perverse subtexts in ordinary horror films a bit more easily. As with Hair, the appeal made to a middle-class audience was one of gentle assault, an affectionate invitation to participate (e.g., instructions on how to dance the ‘Time Warp’ were distributed at the end of every performance of Rocky Horror).

The record and film producer Lou Adler bought the American rights, opened the play in Los Angeles and New York, and went to work on a film version which started shooting at England’s Bray Studios (‘site of the decline and fall of Hammer horrors,’ as Tony Rayns points out) in October 1974. At the London press screening the following summer, the general critical response appeared to be disappointment: once again, a first-rate theater piece had been undone by a crude film adaptation. (‘As [the play] transfers further and further from its fringe origins,’ Jan Dawson noted prophetically in Film Comment in early 1974, ‘the only worry is that some producer may be tempted to polish and inflate it for the cinema.’) And according to diverse reports, the film was a commercial failure when it opened the following autumn and winter in Britain and the U.S.

***

It was only after this that two publicists –- Bill Quigley and Tom Deegan — persuaded Fox to open the film as a midnight movie in New York, specifically at the Waverly Theater in Greenwich Village, in April 1976. From this point onwards, versions differ as to what happened, and who caused it. The ‘capitalist’ explanation sees the cult which started at the Waverly as little more than a successful business investment (and one, moreover, which earned $3 million the first year, and continues to reap profits for Fox as its 200 prints are kept in constant use). The ‘populist’ or ‘socialist’ explanation, which views the phenomenon more as a grass roots movement — the spontaneous expression of an audience’s collective will — is substantially the one propounded in the cult’s own fan magazines, The Transylvanian and Flash. It was stated even more directly to me by Sal Piro, who helped to start the cult by being one of the first of many spectators to dress up likeone of the film’s characters and then reproduce all his or her gestures precisely beneath the screen, under flashlight beams.

According to Piro (whom I spoke to in the lobby of the 8th Street Playhouse late last August while he was preparing to appear as Janet with the film, which he was seeing for something like the 297th time), all that Fox and the Waverly provided was a minimal amount of ballyhoo, ‘a few balloons’, and the practice of playing the soundtrack record in the auditorium for a few minutes before the film came on. The remaining impetus came gradually from a few isolated individuals, who met and became friends in the process of starting the cult, which quickly spread to other theatres and cities.

One of these ‘pioneers’ — Louis Farese Jr., credited in Flash — began the practice of shouting out ‘appropriate’ lines during pauses in the film in order to supplement (respond to, anticipate, mock or echo) its dialogue. These wisecrack notations — which always seem poised between ridicule and fascination, empathy and analysis –are an essential part of the cult’s ritual; they began prior to the impersonations and mimes of Piro and others, and are today recited by large segments of the audience in unison. Collectively, these lines represent a text that is perpetually changing, a complex of layers at any given performance, consisting of both a traditional catechism and a series of fresher contributions, each of which earns a different reputation and lifespan existentially, like a jazz solo, at the moment of delivery (and ‘democratically,’ in competition with all the others) . . . Presumably the use of props and more general audience participation (the flurries of rice thrown in the opening wedding sequence, and the water pistols and umbrellas brandished to accompany the rainstorm) were embellishments that came later.

The entire ritual is enacted with variations twice weekly at the 8th Street Playhouse and some twenty other movie theatres in the ‘greater New York area’ alone, stretching from Philadelphia to Long Island, as well as some 180 more cinemas nationwide. It can be viewed as an unconscious yet authentic act of film criticism, and one which returns live, in-the-flesh theatricality and confrontation to a flashy work which utterly depends on them. As formal analysis, the ritual even includes at one point a collective cry of ‘Close-up!’ to accompany a cut from long shot to close-up, the second syllable adroitly timed to coincide with the actual cut. (And in The Transylvanian, a column by Piro, ‘Rocky Mistakes,’ describes the film’s continuity and editing errors — much more evident to habitués who’ve seen the film dozens of times -– in some detail.) Finally, the ritual can be seen as a specifically Barthesian act of criticism and commentary on a Text, which is ‘that space where no language has a hold over any other, where languages circulate (keeping the circular sense of the term).’ *

***

One should note, however, that the ritual on 8th Street (where the original Waverly group migrated in January 1978, a few blocks north, after a series of unpleasant incidents with hoodlums) begins an hour or two before the film does. After an extended wait in lineoutside the theatre with other ticket holders (except for veteran performers and guest visitors, who are given passes, allowed to wait in the lobby, and accorded other ‘star’ privileges), there is first of all an established speech by Piro, who welcomes ‘virgins’ (i.e., newcomers) to the cult, introduces out-of-town guest performers — in late August, a black woman from Chicago, dressed as Frank N Furter in drag, who performs later during one of his songs, a spot relinquished to her by the local Curry specialist — and offers a few local rules and guidelines. (‘We don’t call Brad “asshole” every time he appears” And in reference to Charles Gray, the film’s narrator: ‘We like the Criminologist here, we don’t say he has no neck.’) After this, the assembled costumed performers (usually more than a dozen) dance the ‘Time Warp’ to the soundtrack record before the lights dim. Then at least two musical shorts follow — traditionally ones that feature Meatloaf (who plays Eddie, a leather-jacket biker, in the feature), Curry and/or the punk group Devo — before the feature begins.

According to Ed Bordenka — another member of the original Waverly cult, who described himself to me as Piro’s assistant, and sometimes performs as Brad to Piro’s Janet — the episodes which occasioned the move to 8th Street occurred when a group of hoodlums decided they wanted to beat up some homosexuals. Curiously enough, this turn of events corresponds closely to part of the account of an ethnographer, Margery Walker Pearce, who followed the cult over a two-year period on the west coast, at the Strand Theatre in San Diego, attending about 27 performances. She reports that the Saturday night Strand crowd (somewhat in contrast to the Friday night audience, which was composed more of sailors and marines from nearby military bases) underwent a series of major changes during that period (roughly 1976-78), starting mainly as a group of male homosexuals under 2l with a few female friends, and gradually evolving into a mainly heterosexual group of male and female college students.

The turning point occurred when a local newspaper ran a story about the cult, approximately a year after it started locally. Before that, it functioned more or less like a gay bar (and one should add that the film is a particular favorite at certain gay bars in some of the larger American cities). Afterwards, ‘a new group of curiosity seekers came down to the Strand, not enticed by the movie, but to gawk at the customers. ‘ Hard-hat types appeared in truckloads weaving in and out of the crowd with menacing looks and insulting remarks. . . These same people bought tickets and led rousing cheers when Frank N Furter was killed in the movie.’

As a consequence, fewer homosexuals went to the Strand midnight shows, while the hard-hats ‘drifted away to other pursuits’. The audience next became ‘a liberal mixture of the reformed, converted and bored,’ including some curious parents who wanted to see what their children were doing. Then the influence of punk became apparent in the crowds, which placed more emphasis on the violence, leather and chains in the film (and less emphasis on the transvestism and transsexuality). ‘The punkers had the film to themselves for about six weeks before the college crowds arrived to take their rightful place amongst the ranks of radical chic,’ Pearce concludes. ‘The whole experience had been co-opted by straights who, in their groping to be “where the action is,” made it totally impossible for anyone else to feel comfortable. . .’

My own limited acquaintance with the cult — consisting mainly of three shows at the 8th Street Playhouse in New York, and some independent research — has been less partisan than Pearce’s. Thus it has not been clear to me how much of the audiences I’ve been part of have been homosexual or straight. It is quite possible that this ignorance on my part allows for a more favorable, open and idealized impression. And yet the electrically charged energy, as well as the relaxed social warmth and democratic spirit of the three shows I’ve attended is unmistakable. For all the competitive divisions and hierarchies within the cult (e.g., Bordenka complaining to me about another Rocky Horror group picking up new supplementary lines from 8th Street performances and then claiming credit for some of them), a ‘virgin’ is encouraged to feel that he or she can freely contribute almost anything to the collective Text without fear of giving offense — a sense that the ritual, like the film, is an elastic tool to be used, not simply a catechism to be mechanically recited.

Would it be too much to see some of the same principles here as in Renoir’s method of rehearsing actors according to the ‘Italian method,’ Noël Burch’s fascination with such phenomena as the benshi and the mixed-media genre of rensa-geki in the early years of Japanese cinema, and the open forms created by Tati’s multiplication and dispersion of focal points in Playtime? (The latter is extended here beyond the borders of the screen and into the auditorium, so that a non-performing spectator might have the option of viewing Richard O’Brien as Riff Raff on the screen, a teenage male or female performer as Riff Raff in the right or left aisle, or both Riff Raffs alternately — but not both at the same time.) The fact that these and other aesthetic aspects or implications have been overlooked in most accounts of the cult seems a direct function of the difficulty in assigning an auteur or even a recognizable tradition to these manifestations. In short, the cult is still perhaps too adventurous and mysterious — at least in relation to the rest of the cinema — to be taken very seriously in intellectual circles.

It seems important to make these distinctions at a time when so little community feeling is evident or even possible. at cinemas in the U.S., given the steady rise in cable television and video equipment, and new cinemas built in privately owned shopping centers on the outskirts of towns (along with the rapid decline and disappearance of cinemas in public squares, in the centers of towns). In this respect, perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Rocky Horror Picture Show cult is the extent to which it evokes and weirdly resurrects, as if in a haunted house, a form of cinema as community that once flourished in the U.S., when Hollywood was still in its heyday. At that time, going to the cinema was automatically a social event, a night at the movies, even a collective form of self-expression — a moment when one felt proud rather than embarrassed to be sitting next to other people in the dark.

*Roland Barthes, From Work to Text, translated by Stephen Heath, Fontana/Collins, 1977.