From the Chicago Reader (November 6, 1992). — J.R.

THE HOURS AND TIMES

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Christopher Munch

With David Angus, Ian Hart, Stephanie Pack, Robin McDonald, Sergio Moreno, and Unity Grimwood.

A TALE OF SPRINGTIME

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Eric Rohmer

With Anne Teyssère, Hugues Quester, Florence Darel, Eloise Bennett, and Sophie Robin.

It’s easy enough to understand why gay and lesbian film festivals exist, especially at this juncture in history, but I can’t say I’m happy about what they do to classifying films. After all, we don’t have festivals devoted to heterosexuals or dead white men or Catholics or intellectuals or Republicans or Democrats, and I sincerely doubt that any good film should be categorized in so parochial a fashion.

By the time this review appears, we’ll probably have elected a president — our first — who professes to consider gays and lesbians part of the American mainstream, not a “special” category. This fact alone prompts some consideration of what it means to perpetuate such categories, in a film festival or in a review.

Though it’s natural for an oppressed minority to band together — for consciousness raising, among other reasons — the meaning of such events to the public at large is something else. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 26, 1997). — J.R.

Medea

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Lars von Trier

Written by Carl Dreyer, Preben Thomsen, and von Trier

With Kirsten Olesen, Udo Kier, Henning Jensen, Solbjaig Hojfeldt, and Prehen Lerdorff Rye.

Sunday

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Jonathan Nossiter

Written by James Lasdun and Nossiter

With David Suchet, Lisa Harrow, Jared Harris, Larry Pine, and Joe Grifasi.

It’s been disconcerting to read, over the past several weeks, of no fewer than four Hollywood projects in the works that purport to be by and/or about Orson Welles. Three of these are based on Welles scripts that he never found the money to produce: The Big Brass Ring (an original with a contemporary setting), The Dreamers (an adaptation of two Isak Dinesen stories), and The Cradle Will Rock (an autobiographical script set in the 30s). Yet all have been extensively rewritten, and the fourth — as recently reported by Todd McCarthy in Daily Variety — is a series of whole-cloth inventions about the making of Citizen Kane, presumably with a few facts thrown in, called RKO 281, written by Chicago playwright John Logan.

Why is all this money, effort, and media attention being expended on “celebrating” Welles when nobody is showing the slightest interest in making available unseen Welles features like Don Quixote and The Other Side of the Wind? Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 10, 2003), where it was printed under the title “Against the Tide”. — J.R.

While putting together a collection of my film pieces for an upcoming book I included an appendix listing my 1,000 favorite films and videos made between 1895 and the present — features and shorts, live action and animation, narrative and experimental. The point was to cite not the works I consider the most important historically but the ones that still provide me with the most pleasure and edification.

This took more work than anticipated because I didn’t have a surefire method of recalling all the possible candidates. I worried about the inevitable oversights, including even ones from 2002. I also worried that I’d wind up weighting the list with more old than recent films — a fear that proved to be mainly groundless. The year between 1924 and 2002 for which I listed the fewest titles — five — was 1937. Four other years — 1926, 1939, 1942, and 1945 — yielded only six apiece. The peak year was 1955, with 21 titles. Generally speaking, there was a steady rise through the 50s, a decline in the 60s, then a leveling off: 17 items in the teens, 72 in the 20s, 95 in the 30s, 103 in the 40s, 160 in the 50s, 133 in the 60s, 130 in the 70s, 129 in the 80s, and 125 in the 90s. Read more

This appeared in the November 6, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. Reseeing Pleasantville on DVD, I continued to find its diverse perceptions and confusions equally fascinating. On his audio commentary, producer-director-writer Gary Ross alludes to his childhood as the son of an activist screenwriter who was blacklisted, and part of what’s so intriguing about the film is the way its own theme of innocence crossed with sophistication is matched at times by its own multiple forms of ideological doublethink. Ross’s ongoing and seemingly untroubled assumption, for instance, that black and white film is innately artificial and stylized whereas color film is innately “realistic” makes me wonder how he can perceive MGM Technicolor of the 50s as being closer to reality (and thus presumably further away from fantasy) than all the black and white cinematography from the same period — or whether, for that matter, he can even distinguish sufficiently between the alleged “realism” of the contemporary color sections of this film and the subsequent expressionism of the hallucinogenic colors impinging on a 50s sitcom’s black and white to confidently declare that both of these kinds of color are automatically and unproblematically superior to black and white in representing reality accurately. Read more

From the August 11, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Hollow Man

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Written by Andrew Marlowe

With Elisabeth Shue, Kevin Bacon, Josh Brolin, Kim Dickens, Greg Grunberg, Joey Slotnick, Mary Randle, and William Devane.

Apart from Space Cowboys, Clint Eastwood’s enjoyably auteurist swan song, Paul Verhoeven’s latest feature, Hollow Man, was the only summer Hollywood release I’d been looking forward to. For one thing, I’d hoped it would give me an opportunity to reassess his previous works, most of which I now think I underestimated when they were released.

I was pretty hospitable to Total Recall (1990), but I awarded a black dot to Basic Instinct (1992), mainly because I was incensed about the calculations of Joe Eszterhas’s $3 million script (I’m leaving aside Verhoeven’s Dutch movies because the only one I’ve seen is The 4th Man). I declined to review Showgirls (1995) at length, noting somewhat puritanically toward the end of my capsule: “I suppose the overall theory is that male spectators will tolerate any amount of stupidity and unpleasantness for the sake of acres of tits and ass, but you’ve got to hand it to the filmmakers for putting such a theory to the ultimate test: if anyone emerges from this with a smile on his face he must hate women as much as this movie does.” Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1977, Vol. 44, No. 516. Both this film and Mekas’s earlier diary film Walden (1969) have been released together on a Blu-Ray from Kino Lorber. –- J.R.

Diaries, Notes & Sketches — Volume 1, Reels 1-6: Lost Lost Lost

U.S.A. ,1975

Director: Jonas Mekas

Dist–Artificial Eye. p.c /p/sc/ph–Jonas Mekas. addit. ph–Charles Levine, David Brooks, Peter Beard, Ken Jacobs. Part in colour. ed–Jonas Mekas. m/songs–including piano music by Chopin, “Abschied” by Schubert, traditional Lithuanian music, “Kiss of Fire” by Lester Allen, Robert Hill, excerpts from Wagner’s “Parsifal”,“How Deep Is the Ocean” by Irving Berlin, music by Lucia Dlugoszewski. sd/narrator–Jonas Mekas. with–(Reels 1-6) Jonas Mekas, Adolfas Mekas; (Reel 2) Prof. Pakstas, Juozas Tysliava, Stepas Kairys, Zadeikis, George Maciunas and family, Faustas Kirsa, Aleksandra Kasuba, Vytautas Kasuba, Vladas Jakubenas, Jeronimas Kacinskas; (Reel 3) Gideon Bachmann, Dorothy Brown, Sidney Grief, Lily Bennett, Storm De Hirsch, Louis Brigante, George Fenin and son, Arlene Croce, Edouard de Laurot, Ben Carruthers, Leo Adams, Sheldon Rochlin, Frances Starr, Robert Frank, Peter Bogdanovich, LeRoi Jones, Frank O’Hara, Allen Ginsberg, Bremser, Ged Berliner, Dick Bellamy; (Reel 4) Gretchen Weinberg, Herman Weinberg, Dick Preston, Dwight Macdonald, Shirley Clarke, Julian Beck, Judith Malina, Robert Hughes, Nat Hentoff, Norman Mailer, David Stone, Jules Feiffer, Naomi Levine, David Reynolds, Paul Goodman; (Reet 5) Peggy Stefans, Herman Weinberg, Gretchen Weinberg, Marty Greenbaum, Peter Beard, Ed Emshwiller, David Stone, Taylor Mead, Sheila Finn, P. Read more

Commissioned by MUBI for late October, 2019. — J.R.

In Sara Driver’s too small yet varied filmography, her two fiction features, both poetic fantasies — Sleepwalk (1986) and When Pigs Fly (1993) — are bracketed by two other longer films, the 48-minute You Are Not I (a brilliant adaptation of a Paul Bowles story about sisters, narrated by a schizophrenic, 1981) and the 78-minute documentary Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat (2017). Sleepwalk stars Suzanne Fletcher, who also played the schizophrenic sister in You Are Not I; Boom For Real portrays both a highly interactive community and an eclectic artist inside it, which might also describe When Pigs Fly, a comedy inspired by Topper about a jazz pianist (Alfred Molina) living in an east coast port town populated by barflies and ghosts. Moreover, the community in Boom is basically Lower East Side Manhattan and more specifically the Bowery, the setting of Sleepwalk, as well as the New York neighborhood where Driver has lived with Jim Jarmusch for well over three decades. (She produced his first two features, and plays one of the zombies in The Dead Don’t Die.)

I’ve known Driver since the 1980s, and suspect that one reason why she hasn’t become better known is that she’s both a woman and a surrealist, a combination that isn’t widely recognized in this country. Read more

I wrote the Preface to this 1973 article in 2009 for its eventual reprinting in Kazan Revisited, edited by Lisa Dombrowski (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011). Note (early 2013): My favorite Kazan film, Wild River, has been released on Blu-Ray, and it looks better than ever. — J.R.

Preface (2009): Rereading this essay 36 years after I wrote it for Richard Roud’s two-volume critical collection, Cinema: A Critical Dictionary – The Major Filmmakers (New York/The Viking Press, 1980), I can’t say that many of my positions or preferences regarding Kazan’s work have changed. But in a few cases I’ve been able to amplify some of my original impressions. For my 2007 essay “Southern Movies, Actual and Fanciful: A Personal Survey” (to be reprinted in my 2010 University of Chicago Press collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephila), for instance, I discovered that Kazan hired speech consultant Margaret Lamkin for his stage production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and then again for Baby Doll, to ensure that all the southern accents heard were letter-perfect. And the significance of Kazan having given the names of former friends or colleagues to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952 — not in 1954, as my article stated — became a more prominent feature in his career profile when he was given a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999, almost half a century later, from the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences. Read more

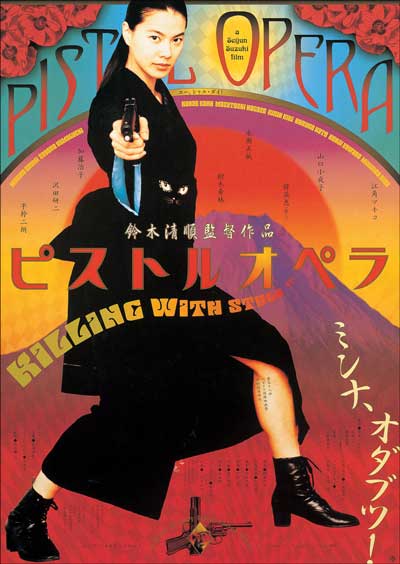

This appeared in the August 22, 2003 Chicago Reader, and has more recently been reprinted in the excellent Camera Lucida. On the afternoon of September 17, 2014, in Sarajevo at the Film.Factory, I screened this for the MA students and assigned them to create five-minute remakes. We screened most of the results nine days later at a party, and they were really dazzling — and all quite different from one another. — J.R.

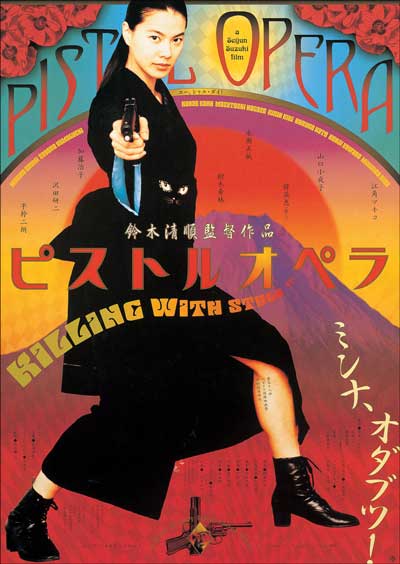

Pistol Opera

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Written by Kazunori Ito and Takeo Kimura

With Makiko Esumi, Sayoko Yamaguchi, Masatoshi Nagase, Kan Hanae, Mikijiro Hira, Kirin Kiki, Haruko Kato, Yeong-he-Han, and Jan Woudstra.

Can I call a film a masterpiece without being sure that I understand it? I think so, since understanding is always relative and less than clear-cut. Look long enough at the apparent meaning of any conventional work — past the illusion of narrative continuity that persuades us to overlook anomalies, breaks, fissures, and other distractions we can’t process — and it usually becomes elusive. Yet it’s also true that we have different ways of comprehending meaning. I once watched some children listen to passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, possibly the most impenetrable book in the English language, and saw them burst into giggles, plainly understanding better than the adults that this was exactly the way grown-ups talked, only funnier. Read more

The following was commissioned by and written for Asia’s 100 Films, a volume edited for the 20th Busan International Film Festival (1-10 October 2015). — J.R.

To explain why Lee Chang-dong’s extraordinary Poetry (2010) is my favorite Korean film, I first need to confess to a feeling of alienation from a good many other South Korean films and what I regard as their excessive reliance on rape and serial killers as subjects. Admittedly, these themes are by no means restricted to South Korean cinema or even more generally to Asian cinema, but they also help to account to my resistance to such highly praised European touchstones involving rape as Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring and Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers (both 1960), and such American films regarding serial killers as Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Ethan and Joel Coen’s No Country for Old Men (2007). The tendency of all these films to exploit and/or sentimentalize these subjects is scrupulously avoided by Lee and handled throughout with tact, delicacy, and a finely nuanced sense of development in its heroine’s ethical and aesthetic consciousness. Consequently, Poetry offers a profound social critique by addressing the theme of rape and its role in Korean society quite directly,

The film centers on the suicide by drowning of a suburban, small-town schoolgirl who had been raped by several of her teenage classmates. Read more

How film history gets rewritten

I realize it must sound crazy for people who haven’t seen Jacques Rivette’s 750-minute Out 1 (1971) or his 255-minute Out 1: Spectre (1972) to keep reading blog posts about them — even though I keep hearing almost every day from various others who have seen either or both films recently, in Chicago or New York or Vancouver or Berkeley, and are still recovering from the experience.

What I’d like to focus on here is how these films wind up getting misrepresented due to the circulation of incomplete data. For instance, everyone who’s seen any stills from the two films and hasn’t seen the films probably concludes that they’re both in black and white. They’re wrong; the problem is that the only photos available from the films on the Internet and in film magazines are in black and white, undoubtedly because color stills would cost too much money to process. In fact, the beautiful restoration of Spectre that showed at the Gene Siskel Film Center last Saturday, blown up from 16-millimeter to 35, had far more luscious and luminous colors than any other print I’ve ever seen — finally justifying Rivette’s supposedly extravagant claim in a 1975 interview that “you might almost say that I am trying to bring back the old MGM Technicolor!

Read more

From Cinema Scope #16 (Fall 2003). — J.R.

One of the more fascinating things about the linguistic options of DVDs in relation to their nationality is how often they confound expectations. It would appear that few countries show more indifference to other countries and their languages than the U.S., yet the DVDs with the greatest number of subtitling and dubbing options are often those on American labels. Conversely, when I visited Japan twice in the late 1990s, I was impressed by the cottage industries devoted to teaching foreign languages, which ranged from prime-time TV shows teaching conversational “business” English and Spanish to bilingual movie scripts sold in bookstores, some of them packaged with videos of the same films. But my recent efforts to hunt for Japanese DVDs with English or French subtitles have been in vain -— which is all the more frustrating when I come across listings for box sets devoted to Kiarostami and Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinéma.

Attending Cinema Ritrovato, an archival film festival, in Bologna last summer, I went hunting for Italian DVDs and quickly discovered that those with Italian movies almost never come equipped with English subtitles (the restoration of The Leopard, which I noted in my last column, is a rare exception). Read more

Into Barbarism

The following is an edited transcript of remarks delivered by Jonathan Rosenbaum at High Concept Laboratories in Chicago on June 5, 2014. Mr. Rosenbaum and the other two panelists were asked to respond to The Point’s issue 8 editorial on the new humanities.

●

I’m the odd person out in this gathering because I’m not an academic, although I teach periodically in various, most often relatively unacademic, situations. And plus, I could be described as a failed academic. Before I came to Chicago I was teaching for four years at the University of California, Santa Barbara, but prior to that I actually began my failed academic career in the U.S. where Robert Pippin had his background, at UC San Diego. And in between I was an adjunct at NYU, at the School of Visual Arts, etc.

My academic background, actually, was in English. I was an English major as an undergraduate and in graduate school I did everything but a dissertation in English and American literature. But then I went to Europe and ended up being a journalist. And the reason why is that I had reached the point of alienation in graduate school where I was actually making a point of reading college outlines rather than the literary texts because I didn’t want them ruined — I wanted to read them in my own time, whereas what they needed in terms of my papers could better be fulfilled by reading the college outlines than by actually reading the texts. Read more

Written for Criterion’s laserdisc release of Parade and apparently posted on its web site (criterion.com) — at least if it had a web site that early — on March 31, 1991. — J.R.

It seems incredible that it’s taken seventeen years for a film as truly great as Parade — Jacques Tati’s final work — to become available in the U.S., and that it’s reaching the public, for the first time, on laserdisc. But old habits die hard, including our biases about technology as well as spectacle. Tati was the first major filmmaker to shoot a feature in video, and he brought to this challenge the same sort of innovative craft that he brought to the movie — although the technical options available in video in 1973 were far from what they are today. He began by shooting with an audience at a circus in Sweden for three days, using four video cameras. Then, he spent 12 days in a studio reshooting portions of the stage acts on film.

The first “gag” in Parade takes place in front of a theater and is so subtle it hardly qualifies as a gag at all. A teenager in line picks up a striped, cone-shaped road marker on the pavement and dons it like a dunce cap; his date laughs, finds another road marker, and does the same thing.

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1993). — J.R.

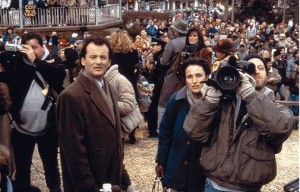

Bill Murray plays an obnoxious TV weatherman from Pittsburgh forced to relive the same wintry day in a small Pennsylvania town over and over again until he gets it right, in an unexpectedly graceful and well-organized comedy (1993) directed and cowritten by Harold Ramis. While the movie’s underlying message is basically A Christmas Carol strained through It’s a Wonderful Life — hardly a recommendation in my book — the filmmakers mercifully spare us the speeches and simply demonstrate their thesis; as they do they reveal their true virtue: a fluid sense of narrative that works the story’s theme-and-variations idea with a glancing and gliding touch. Considering that none of the characters is fresh or interesting, it’s a commendable achievement that the quality of the storytelling alone keeps the movie watchable and likable. With Andie MacDowell and Chris Elliott. PG, 103 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more