This appeared in the November 6, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. Reseeing Pleasantville on DVD, I continued to find its diverse perceptions and confusions equally fascinating. On his audio commentary, producer-director-writer Gary Ross alludes to his childhood as the son of an activist screenwriter who was blacklisted, and part of what’s so intriguing about the film is the way its own theme of innocence crossed with sophistication is matched at times by its own multiple forms of ideological doublethink. Ross’s ongoing and seemingly untroubled assumption, for instance, that black and white film is innately artificial and stylized whereas color film is innately “realistic” makes me wonder how he can perceive MGM Technicolor of the 50s as being closer to reality (and thus presumably further away from fantasy) than all the black and white cinematography from the same period — or whether, for that matter, he can even distinguish sufficiently between the alleged “realism” of the contemporary color sections of this film and the subsequent expressionism of the hallucinogenic colors impinging on a 50s sitcom’s black and white to confidently declare that both of these kinds of color are automatically and unproblematically superior to black and white in representing reality accurately. For me, this is a good example of ideological innocence of the purest kind. —J.R.

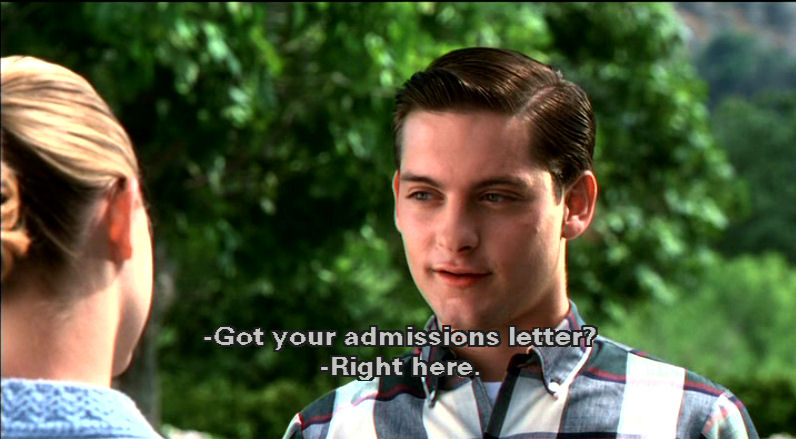

Pleasantville

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Gary Ross With Tobey Maguire, Jeff Daniels, Joan Allen, William H. Macy, J.T. Walsh, Reese Witherspoon, Don Knotts, Paul Walker, and Marley Shelton.

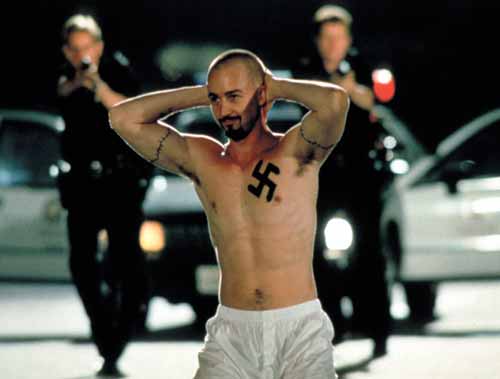

American History X

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Tony Kaye

Written by David McKenna

With Edward Norton, Edward Furlong, Fairuza Balk, Stacy Keach, Jennifer Lien, Elliott Gould, William Russ, Ethan Suplee, and Beverly D’Angelo.

“The movie is sincere about inexplicable mush.” — Manny Farber on Samuel Fuller’s China Gate

A movie of unique ideological derangement that simultaneously demands and defies precise decoding, Pleasantville can be located only superficially in the area sketched out by Robert Zemeckis’s Back to the Future trilogy and the Spielbergian nostalgia that gave rise to it. True, it equates the late 1950s and early 60s with a black-and-white sitcom vaguely recalling The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet [see below] (which, according to the reference book Total Television, is the longest-running sitcom in TV history), and reducing history to television’s depiction of it is central to the postmodernist alienation we’re all floundering in. But consciously or not, Pleasantville generates this confusion not to comment on the past but, far more subversively, to say something heartfelt and profound about the present.

The film opens with teenage hero David (Tobey Maguire) channel surfing until he encounters an ad for an upcoming marathon of Pleasantville, a 50s black-and-white sitcom he’s particularly attached to. (The jeering voice-over, pure 90s patter, promises “family values,” “safe sex,” and a “flashback to kinder, gentler times.”) David spends a desultory day at school, getting rebuffed by the girl of his dreams and learning about the bleak future he and his classmates face — disease, global warming, a shrinking job base. Back home he fights with his promiscuous twin sister, Jennifer (Reese Witherspoon), who’s expecting a hot date at the door any minute; their divorced mother has just driven off for a romantic rendezvous with a guy nine years her junior.

By this time David is ready to settle down to his Pleasantville marathon, but he and Jennifer argue over the remote control, and it smashes into pieces against the wall. A TV repairman (Don Knotts) magically appears at the door a few seconds later with a replacement (his truck bears the slogan “We fix you for good”). As soon as David activates the new remote he and Jennifer are magically transported — from color to black and white — into the living room of the Pleasantville family, replacing siblings Bud and Mary Sue just before they’re called to a gigantic, cholesterol-heavy breakfast by their parents George (William H. Macy) and Betty (Joan Allen).

A calendar reads April 1958, but in fact the clothes and decor are from five or six years earlier — around the same time, in fact, that Ozzie & Harriet was launched on television after almost a decade on radio. And as the new Bud and Mary Sue head off for school, the Pleasantville they encounter is less the 50s than the sitcom version of it — “Nerdville,” as Jennifer/Mary Sue calls it — made surreal by their 90s perspective. No one has sex, the fire department exists only to retrieve cats from trees because nothing burns, the books in the library all carry blank pages, every tossed basketball enters the basket, and no one in school can conceive of anything beyond Pleasantville. Yet it’s only a matter of time before the new Bud and Mary Sue introduce color and other disruptions into this hermetically sealed universe. The color arrives gradually — Mary Sue’s date glimpses a solitary red rose on his way back from having sex with her on Lover’s Lane — and the other disruptions follow in comparable fashion: after the same fellow tells his friends on the basketball court about his sexual encounter, they all miss their baskets.

Ideologically speaking, such fancies seem based on our glib sense of superiority to the past: Gosh, weren’t they naive and simple back then? This might explain why, 40 years later, David loves the show so much that he can recite many of the characters’ lines. Aesthetically we associate this superiority with the superiority of color, which we equate with truth and reality, over black and white, which signifies deprivation and repression. (The movie takes this mutable metaphor a little too far when a merchant, alarmed at the encroachment of color on his black-and-white community, posts a “No Coloreds” [sic] sign in his window; given the total absence of blacks in Pleasantville, it’s a tacky and rather self-satisfied spin on the material.) Yet equating the reality of the 1950s with hokey black-and-white TV from the same period is itself a simple, naive conceit belonging squarely to the 90s — a quaint, industrially produced falsehood that deserves to be shelved beside the fiction that Quentin Tarantino is an independent filmmaker.

For that matter, if we step outside 50s sitcoms for a moment and consider Hollywood movies of the same period, we find a significant body of social criticism, which is much more scarce today than it was then. I’m thinking of movies like Ace in the Hole (aka The Big Carnival), All That Heaven Allows, Bigger Than Life, Blackboard Jungle, Edge of the City, High Noon, Johnny Guitar, Kiss Me Deadly, My Son John, On the Waterfront, The Phenix City Story, Rebel Without a Cause, The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!), The Steel Helmet, Sweet Smell of Success, Touch of Evil, While the City Sleeps, The Wild One, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, and The Wrong Man. These are the first 20 titles that come to mind — all but five of them, incidentally, in black and white — but one could easily compose a list three times as long. If the 50s were as repressed as Pleasantville suggests, how did they produce so many films that are highly critical of social problems?

To say that movies like these are no longer being made would be an exaggeration, yet there are so few that they invariably hark back to the 50s pictures in various ways. The use of a “heroic” French horn behind the opening credits of American History X, which opens this week, is a subtle but telling example; a more obvious one would be the black high school principal in the film (Avery Brooks), an enlightened teacher/parent figure echoing Glenn Ford in Blackboard Jungle (see below), the cop named Ray in the first scene of Rebel Without a Cause, and Karl Malden in On the Waterfront, among many others.

Pleasantville (the movie, not the sitcom) offers a critique of our society too, but producer-director-writer Gary Ross has to be far more circumspect — in other words, repressed — to get away with it. Nowadays terms like “liberal” and even “politics” suffer the same beleaguered cultural status as black-and-white movies. And the freedom to say fuck doesn’t exactly constitute an enlarged understanding of life’s possibilities. Certainly in the 50s Americans were intolerant of intellectuals (known then as “eggheads”), and mainstream TV denied the larger culture even more resolutely than it does today. (I can still recall Bert Parks’s dry-cleaned rendition of “Blue Suede Shoes”: “You can burn my house, steal my car, drink my soda from a soda jar” — whatever that meant.) But as Pleasantville amply shows, the smoldering discontents of that era found a greater voice, in figures ranging from Elvis Presley to Dave Brubeck and Miles Davis, than we could possibly find in today’s corporate packages; in those days the purveyors of entertainment hadn’t yet learned to program the rage and passion and formal playfulness, along with the audience’s responses to them.

When the movie charts the discovery of painting and literature in 50s middle America, it seems to be saying — quite absurdly — that such a discovery required the influence of two 90s teenagers. But what it’s actually proposing — or at least dreaming about — is a return to the presumed innocence of the 50s, an innocence that would allow us to discover art and literature today. When Jennifer/Mary Sue concludes that reading about sex in Lady Chatterley’s Lover is even better than having sex, the 50s are becoming a catalyst for the openness of the 60s (the U.S. ban on Lady Chatterley’s Lover was lifted in 1959). The three tenderest moments in the movie — David/Bud applying gray rouge to his mother’s pink cheeks so she can look like everybody else (see below), soda jerk Mr. Johnson (Jeff Daniels) rubbing off the same rouge to help her accept her newly discovered sexuality, and back in the grim 90s, David wiping the tears from his own mother’s cheeks — imply that we’re all painters at heart, even if the colors are usually in short supply. Extending this metaphor, the movie suggests that the 50s generated the colors that teenagers in the 60s began to paint with.

The fact that the movie has connected so quickly, readily, and even beautifully with the mass audience is partly a testimony to Ross’s deft handling of his actors. But surely that same audience recognizes how deprived we are in the 90s, a point made explicit only in the film’s prologue and epilogue. Pleasantville pretends to show how the life-enhancing spirit of the 90s brings color and flavor to the moribund 50s, yet in fact it does something much closer to the reverse. Just as we need the apparent simplicity of black and white to apprehend “true” color, we need the apparent simplicity of the 50s to bring life and art to the 90s.

The major formal pleasure of Pleasantville is the gradual and parsimonious way it introduces color into a black-and-white town, joyfully reinventing our perceptions of both color and black and white. (Interestingly enough, a variation of the same technique can be found in a recent first feature from Kyrgyzstan, Aktan Abdikalikov’s The Adopted Son, which won a prize at the Locarno film festival last August — shot mainly in black and white, it employs brief color passages to poetic effect.) In the 90s we’re encouraged to interpret this transformation as something pale and incomplete becoming full-bodied and “real,” yet it’s worth noting that the color taking over Pleasantville is less the standard 90s color of the opening and closing sequences than the lush, confectionlike Technicolor of MGM musicals of the 40s and 50s [see first two photos below, from The Pirate and On an Island with You, for two samples of what I mean], a Hollywood vision of Eden pinpointed when a girl offers a boy a red apple. In these terms color is important not because it offers us reality but because it promises some “forbidden” aesthetic bliss usually kept out of reach by the 90s thought police. The standard 90s color seen at the beginning and end of the film [see third photo below, with subtitles] offers no bliss at all, only the depressing banality of what’s deemed obligatory to everyday contemporary entertainment.

Clearly the ideological implications of black and white and color in contemporary films are complex and slippery. In his exciting and suggestive new book, More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts (University of California Press) — probably the best, most far-reaching study of film noir ever written — James Naremore presents the beginnings of a strategy for sorting out some of these problems, though as he points out, the enormity of the issue prevents us from mastering all its implications. According to Naremore the postmodernist construct of noir virtually constitutes our cultural world; contemporary neo-noir films in color are only one tip of this iceberg, and the paradoxes of Pleasantville are clearly related.

When American History X resorts to black and white, it does so more prosaically, to signify the past — even an incident that took place only a few hours earlier. It’s a black-and-white movie filmed in color, a choice that robs it of any period flavor, but given its 50s pedigree of social comment, such a nuance is hardly necessary. Director Tony Kaye wants to say something about what produces a skinhead today, and though he doesn’t succeed fully in this endeavor, he does take us a significant part of the way. The film’s flashback structure, which recalls several noir classics, may partially account for Kaye’s decision to film the flashbacks in black and white; the question of what produces a racist skinhead — and what might subsequently prompt one of them to overcome his racism — is posited as a mystery in which the black-and-white flashbacks serve as “evidence”.

Mike Leigh’s Meantime (1983) offered a more cohesive attempt to describe what produces an English skinhead in London’s East End; the designated turf of American History X is Los Angeles’s Venice Beach. Like Leigh’s effort, American History X concentrates on the relationship between two brothers (though it’s important to add that the relationship between the brothers in Meantime is largely hostile whereas the one in American History X is deeply affectionate). Screenwriter David McKenna is a 28-year-old native of Orange county, yet Kaye is English, so it’s plausible that he used Meantime as a reference point.

Best known as a director of TV commercials, Kaye has been publicly disavowing the release version of American History X, complaining that among other things he wasn’t allotted more time to prepare his own cut. Some reports suggest that he’s behaving like a prima donna, yet the film’s narrative does feel choppy and slightly unfinished (the ending, for instance, seems needlessly abrupt), and more significantly, there’s an excessive and cliched reliance on slow motion to stretch out certain dramatic moments.

The fact that the movie is constructed like a mystery inevitably creates certain narrative expectations that the script’s own exploratory methods, defensible on their own terms, aren’t always equipped to satisfy. The film’s unfinished feel mainly derives from a conceptual problem — an attempt to combine the more “classical,” symmetrical aspects of 40s noir and 50s social-problem films with a mode of investigation more readily identified with the rougher, semi-improvisational filmmaking of the 60s and afterward.

It might seem unexceptional that the movie traces the racism of its two skinhead brothers back to their troubled family life and confused sense of identity. But the performances of Edward Norton and Edward Furlong are so intelligently nuanced and sympathetically detailed that this never comes across as a simple thesis film, even if it periodically uses a few theses as stepping stones for its investigation. (One of the most persuasive of them is the idea that the older brother’s racial notions are altered by the reversed social hierarchies of prison, in which poor whites become the “niggers.”) The film is especially good with some of its secondary characters — a white-power guru played by Stacy Keach, an overweight skinhead played by Ethan Suplee — and with its various family quarrels and neighborhood rabble-rousing speeches. Given the propensity of most current movies to deny the world we’re living in — which leads to the muddled strategies of Pleasantville — this one exhibits an uncommon amount of curiosity and courage in exploring what most flacks would regard as distasteful subject matter: the spread of racism and xenophobia among young people. What a pity that we still have to reach back to the “black-and-white” 50s to find appropriate models for this curiosity and courage rather than look for new forms in the drably colorful present.