Commissioned by the Chicago Reader in September 2016. — J.R.

This gripping Iranian melodrama by writer-director Asghar Farhadi (the Oscar-winning A Separation) focuses on a couple acting in a Tehran production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. One should probably resist the temptation to read some subtle message into this exotic premise, because Farhadi (unlike Abbas Kiarostami) is neither a modernist nor a postmodernist but something closer to Elia Kazan: topical, sharp with actors, mildly sensationalist (this is about the consequences of a woman being attacked by a stranger while taking a shower), alert to moral nuances, but lacking a full-blown vision of his own. As in A Separation, Farhadi privileges a woman’s viewpoint without either sharing or exploring it. (Jonathan Rosenbaum)

Read more

Read more

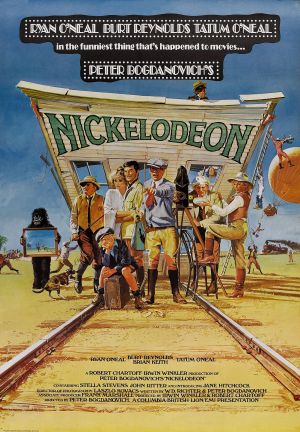

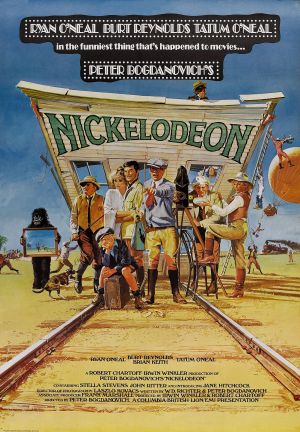

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977 (Vol. 44, No. 517). Over 30 years later, in my DVD column for Cinema Scope, I wrote, “Is it possible to find a picture acceptable only with its director’s commentary? Yes, if it’s Peter Bogdanovich’s clunky but interesting comedy about American moviemaking during the patent wars (1910-1915), prior to The Birth of a Nation, now that he’s finally had a chance to release it in black and white, as he originally intended, and recut it as well. Reviewing this when it came out…, I found its slapstick mainly irksome — not offensive, as it was to me in What’s Up, Doc?, where so many of the pratfalls, collisions, and smashups seemed to be about fatuous, narcissistic yuppies humiliating servants and carpenters, but pretty academic none the less…. It still looks academic, but hearing Bogdanovich explain where all the stories come from (mostly from Dwan, Ford, McCarey, and Walsh, with a curtain-closer from James Stewart) makes it somewhat more absorbing.” — J.R.

Nickelodeon

U.S.A./Great Britain, 1976

Director: Peter Bogdanovich

Chicago, July 30, 1910. Fleeing from a divorce court when he discovers that his client has an indefensible case, lawyer Leo Harrigan stumbles into H. Read more

From the October 24, 1997 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Small, quiet virtues are rare enough in American movies these days, but to find them in a bittersweet autobiographical script by none other than Joe Eszterhas — about growing up as a green Hungarian immigrant in early 60s Cleveland — is a genuine shock. Yet I have to admit that earlier Eszterhas-scripted movies such as Basic Instinct and Showgirls, for all their grotesqueries, have gradually become guilty pleasures of mine; there’s something touching about his honest primitivism. When the grotesquerie’s removed — as it has been under the thoughtful direction of Guy Ferland (whose only previous feature is The Babysitter) — what emerges is solid and affecting. Brad Renfro plays a shy, 17-year-old compulsive liar who goes to work for a master, a payola-happy rock DJ (Kevin Bacon in his prime) named Billy Magic. What the kid winds up discovering — like the hard discoveries in Elia Kazan’s America, America — is more nuanced than you might think. The period detail is mostly perfect and the casting of certain minor parts (such as Luke Wilson as an egg-market manager) sublime, and the purity of feeling recalls exercises in nostalgia on the order of The Last Picture Show. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 24, 1989). — J.R.

SEX, LIES, AND VIDEOTAPE

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Steven Soderbergh

With Andie MacDowell, James Spader, Laura San Giacomo, and Peter Gallagher.

As its lowercase title suggests, sex, lies, and videotape is an example of lowercase filmmaking: lean, economical, relatively unpretentious (or at least pretentiously unpretentious), and purposefully small-scale. Its having walked off with the Cannes film festival’s Palme d’Or — making first-time writer-director Steven Soderbergh at 26 the youngest filmmaker ever to win that prize — saddles it with more of a reputation than it can comfortably live up to. In a time of relative drought, it’s certainly a small oasis, but the attention it’s been getting befits something closer to a breakthrough geyser.

All the fuss may be a sign of panic over more than just movies. Sexual repression is reflected in various ways in current pictures, but this is the only one that deals with it forthrightly as its central subject — specifically, as the main preoccupation of its two leading characters — and broaches sexual problems such as impotence and frigidity in the bargain. I haven’t heard such giddy, unnatural-sounding laughter in a movie theater since The Decline of the American Empire hit the art-house circuit a few years ago — the same sort of forced, hyped-up hilarity at the mere mention of words like “fucking” and “penis” and “getting off.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 12, 1992). — J.R.

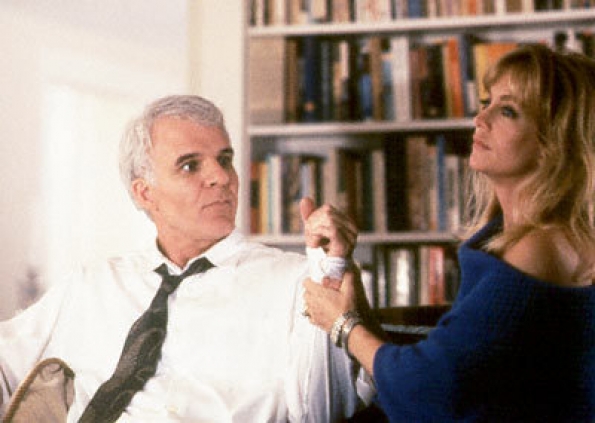

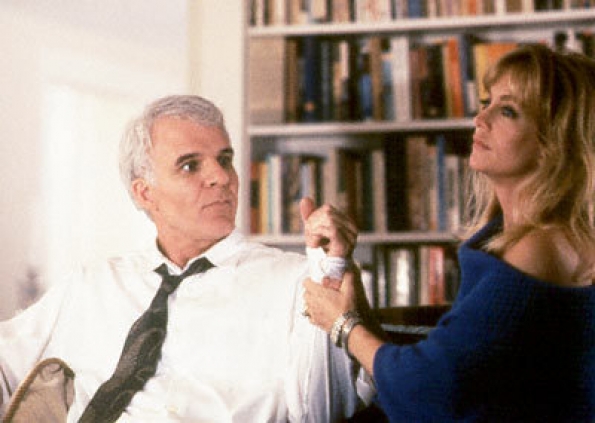

HOUSESITTER

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Frank Oz

Written by Mark Stein and Brian Grazer

With Steve Martin, Goldie Hawn, Dana Delany, Julie Harris, Donald Moffat, Peter MacNicol, Richard B. Shull, Laurel Cronin, Roy Cooper, and Christopher Durang.

I’ve seen previews of two summer comedies so far — Sister Act and Housesitter — that have elicited gales of hysterical laughter from their mainly young audiences. In both cases the hysteria and volume of the laughter seemed a bit out of proportion. The one-joke premise of Sister Act — that there’s something indescribably hilarious about nuns behaving slightly irreverently — smacks more of quiet desperation growing out of repression than of something to feel happy about. I suspect that if I were a Catholic I’d feel more offended than charmed by the complacency of this running gag, whatever Emile Ardolino’s efficiency as a director. There’s a certain darkness behind many of the laughs in Housesitter, too, but at least they relate to a zeitgeist I can feel part of.

The main comic staple of Housesitter, apart from the enjoyable physical clowning of Steve Martin and Goldie Hawn, is a theme I associate especially with the comedies of Billy Wilder: the baroque complications that grow out of elaborate lies. Read more

These exceptional personal documentaries add up to a potent double bill; of the nonfiction films in the festival that I’ve seen, these are in many ways the best. Deborah Hoffman’s Complaints of a Dutiful Daughter, which deals only in passing with the fact that the director’s a lesbian, is a beautifully precise, acute, intelligent, practical, touching, and even (at times) comic record of how she copes with her discovery that her mother has Alzheimer’s disease. Using video and audio recordings of her interactions with her mother and some on-camera statements of her own, Hoffman charts in haunting detail precisely what memory loss entails, not only for her mother but for herself as she adjusts to the situation. Full of wisdom and insight, this 44-minute essay film is far from depressing. The same is true of Gregg Bordowitz’s 54-minute, deconstructive Fast Trip, Long Drop (1993), an autobiographical essay about the filmmaker’s 1988 discovery that he’d tested HIV-positive and his subsequent life, including his decision to quit drugs and drinking and come out to his mother and stepfather. Making semi-ironic use of silent found footage and Jewish music, Bordowitz speaks about his late father and his sex life; he also includes conversations with various friends (including filmmaker Yvonne Rainer), his own documentary footage of AIDS rallies, a tour of his bookshelves, and a bitter parody of the way the media have treated AIDS. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 21, 2002). — J.R.

I haven’t been much of a John Woo fan, and war films aren’t my cup of tea, but this World War II epic made me reconsider both biases. The masterful storytelling, which doesn’t seem overextended even at 134 minutes, focuses on the unlikely friendship between a shell-shocked marine (Nicolas Cage) returning to combat in time for the battle of Saipan in 1944 and the Navajo Indian he’s assigned to guard (Adam Beach of Smoke Signals), who’s been trained to transmit messages in a code based on his native language. The material yields a powerful story more realistic in premise and treatment than Woo’s usual fare (the depiction of American wartime racism is especially sharp), yet it’s clearly a personal project that gratifies his penchant for both male bonding and dramatic action sequences. Despite some of the sentimentality that is also Woo’s stock-in-trade, I was moved and absorbed throughout. Written by John Rice and Joe Batteer; with Peter Stormare, Noah Emmerich, Mark Ruffalo, Martin Henderson, Roger Willie, Brian Van Holt, Frances O’Connor, and Christian Slater. Century 12 and CineArts 6, City North 14, Crown Village 18, Esquire, Ford City, Gardens 7-13, Golf Glen, Lake, Lincoln Village, Norridge, Three Penny, Village North. Read more

A column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, written November 16, 2016. — J.R.

En Movimiento: The Man Who Would Be King

Errol Morris: “If you could give Charles Foster Kane advice, what would you say to him?”

Donald J. Trump: “Get yourself a different woman.”

— from a 2003 interview

It isn’t surprising that Citizen Kane is Donald Trump’s favorite movie. Thanks to the input of Herman J. Mankiewicz, an unhappy cynic, Orson Welles’ first feature is the only one he ever made that views corruption from a corrupted viewpoint; all the others see corruption from a vantage point of baffled innocence. As an actor who specialized in playing corrupt authoritarian figures — tycoons (Kane, Arkadin, Charles Clay), racists (Kindler, Quinlan), conniving magicians (Cagliostro, Welles himself in Follow the Boys and F for Fake), power-mad officials (Colonel Haki in Journey into Fear, Cesare Borgia in Prince of Foxes, the Advocate in The Trial), a sly racketeer (Harry Lime), and several dissolute rulers—before achieving his best role as Falstaff, an innocently jovial jester to a prince, which failed to engage the mass audience to the same degree (as did his more innocent heroes in The Lady from Shanghai and Othello) — Welles as an anti-authoritarian writer and director only confused matters for the general public by undermining what he celebrated as a performer. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 2000). — J.R.

Conceived as a kind of irreverent parody of both Rififi and The Asphalt Jungle, Mario Monicelli’s stumblebum heist film (1958) about a group of incompetent crooks trying to rob a safe full of jewels is one of the funniest Italian comedies ever made — certainly much funnier than the many imitations and remakes (i.e., rip-offs) it’s spawned over the years, including Louis Malle’s Crackers and Woody Allen’s Small Time Crooks. Monicelli’s sense of character is priceless, and his fabulous cast — including Marcello Mastroianni, Vittorio Gassman, Claudia Cardinale, and Renato Salvatori — makes the most of it. 111 min. (JR) Read more

Unfortunately, Richie’s division of Ozu into successive stages of ‘creation’ inevitably leads to the erection of a Platonic ideal, an all-purpose model of ‘the’ Ozu film — an unrigorous model indeed when what one concretely has to contend with are films, each with its own peculiar set of conditions and stresses. Since Richie has more production details about the later films, these tend to dictate most of the dimensions of the model, and the lost films implicitly become subsumed in the same homogenising process whenever Richie speaks about the entire body of the work. The usual approach is to lump together examples of certain aspects or procedures, leading to the formulation of such generalities as ‘the Ozu family’. This results in a profusion of catalogues, some quite nonsensical in presumed meanings and applications: ‘Another pastime to which the Ozu family is addicted is toenail cutting, an activity which seems worth mentioning because it occurs possibly more often in Ozu’s pictures (Late Spring, Early Summer, Late Autumn) than in Japanese life.’ In the long run, individual works are made to seem important or unimportant insofar as they help or fail to exemplify the hypothetical model.

Problem No. Read more

For the beginning of this article, go here.

While one could hardly claim that Days of Youth is a major work, it is at the very least an arresting one, and some of its comedy is on a par with the wonderful opening sequence of Passing Fancy (1933) at a naniwabushi recital (when a stray purse gets surreptitiously picked up, investigated, and tossed around like a beanbag by various spectators until the. entire assemblage, reciter included, is dancing about from an attack of lice). One would expect, then, that any serious Ozu scholar would pay some heed to it. Yet all that Richie has done in Ozu — apart from noting at one point that, like all of Ozu’s subsequent films, it shows actors directly facing the camera — is to expand his original commentary on the film (in Film Comment, Spring 1971) from five words (‘A student comedy about skiing’) to seven: ‘Another student comedy, this one about skiing.’ And if one searches in his book for something about Tatsuo Saito — an actor who went on to play the father in I Was Born, But . . . (1932), and figured centrally in several of the twenty other Ozu films where he appeared — one finds that he isn’t even listed in the index; in fact, the only reference to him in the entire book is the observation that he ‘keeps rubbing his hip during various scenes’ in Tokyo Chorus. Read more

From The Financial Times (July 4, 1975); this was the first of my two annual weekly film columns for that newspaper, replacing Nigel Andrews as his “deputy” while he was away.

A couple of asides: I had attended the press conference at Cannes for The Panic in Needle Park, and recall being disturbed by the heartlessness with which Didion and Dunne described their dispassionate and seemingly indifferent “research” about New York addicts. And on the matter of Mizoguchi, I would no longer define Yang Kwei Fei as any sort of “masterwork,” and am still making up my mind about Street of Shame.–- J.R.

To score or not to score

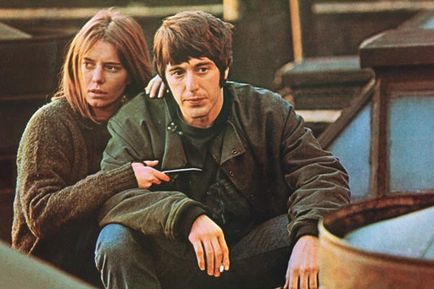

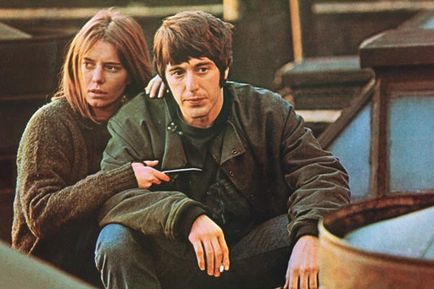

The Panic in Needle Park (X)

Berkeley 1

Diagnosis: Murder (A)

Plaza 2

Brewster McCloud (A)

Electric Cinema

Ugetsu Monogatari (X)

National Film Theatre

Of the two new releases on offer this week, The Panic in Needle Park is the better of an impossibly gloomy choice. Arriving here four years after its premiere at the Cannes Festival (where its female lead, Kitty Winn, was awarded Best Actress prize) — a delay apparently caused by its graphic depiction of heroin rituals being deemed unfit for local consumption — it offers at least one potential source of interest which was less evident in 1971: Al Pacino in his first major movie role. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 492). — J.R.

Machorka-Muff

West Germany/Monaco, 1963 Director: Jean-Marie Straub

Germany, in the early 1950s. Colonel Machorka-Muff arrives in

Bonn to see his mistress Inn and continue his efforts to clear the

name of General Hürlanger-Hiss from disgrace after his retreat at

Schwichi-Schwalache during World War II. At his hotel the next

morning, after meeting and exchanging pleasantries with a lower

rank officer he commanded, he also sees Murcks-Maloche from the

Ministry, who informs the Colonel that he is to give the dedication

address at the foundation-laying ceremony to inaugurate the

Hürlanger-Hiss Academy of Military Memories. After the Colonel

spends the morning walking through Bonn, Inn picks him up in her

Porsche and they drive to her flat and make love. She wakes him a

few hours later to announce the arrival of the Minister of Defense,

who presents him with a general’s uniform and drives him to the

ceremony; there Machorka-Muff announces in his dedication that

Hürlanger-Hiss made his retreat after losing 14,700 men, not “only”

8,500 as previously-thought. At mass the next morning, Inn

recognizes the second, fifth and sixth of her seven former husbands,

and Machorka-Muff announces that he will be the eighth; afterwards,

the priest explains that there will be no problem in having a church

wedding because all of her former marriages were Protestant ones. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 508). — J.R.

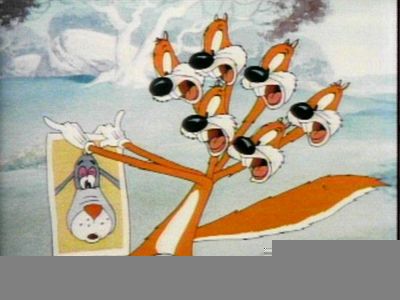

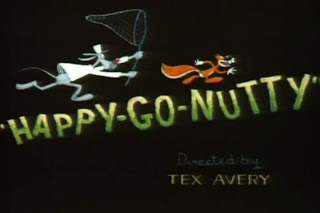

Happy-Go-Nutty

U.S.A.,1944

Director: Tex Avery

Cert–U- dist–Ron Harris. p.c—MGM. p–Fred Quimby. story–Heck AIIen. col–Technicolor. anim–Ed Love, Ray Abrams, Preston Blair. m–Scott Bradley. 260 ft. 7 mins. (16 mm.).

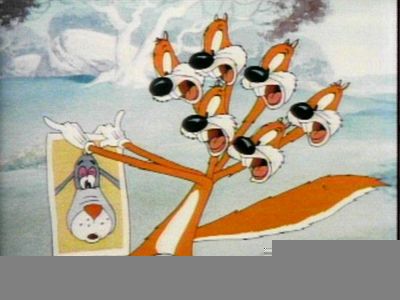

Breaking out of the confines of Moron Manor and deliberately rousing Meathead the watchdog, Screwy Squirrel flees from him through a series of violent adventures Running past the cartoon’s end title, the antagonists return to discuss other possible endings until Meathead goes mad himself, bursts through the end title, and runs away; Screwy praises this ending for its silliness. A little less impired than Screwball Squirrel, its immediate predecessor, Happy-Go-Nutty nevertheless registers as a kind of ode to dementia, particularly of the gibbering and Napoleonic-complex variety. After beglnning with its hero in a loony bin (“Through these portals pass the screwiest squirrels in the world”), it proceeds spiritedly through some familiar gags (a bomb momentarily turning Meathead into a pickaninnv), some more inventive surreal ones (Meathead goes over a cliff. only to be handed a newspaper by Screwy when he lands, with the headline “SUCKER!!” over a photograph of Meathead going over a cliff), and odd throwaway details (a trashcan labeled “for extra squirrels”). If it fails to scale the summits of imagination displayed by Avery’s team at MGM, it does allow everyone involved more scope for their talents than most cartoons. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, November 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 514). –- J.R.

Foolish Wives

U.S.A., 1922

Director: Erich von Stroheim

Cert—A. dist–BFI. p.c–Universal Super Jewel. p–Carl Laemrnle. asst. d–Edward Sowders, Jack R. Proctor, Louis Germonprez. special asst. to Stroheim–Gustav Machaty. sc–Erich von-Stroheim. ph–Ben Revnolds, William Daniels. illumination and lighting effects—Harry J. Brown. ed–Erich von Stroheim, (release version: Arthur D. Ripley). a.d—E. E. Sheeley, Richard Day. scenic artist—Van Alstein [Alstyn]. technical d–William Meyers, James Sullivan, George Williams. sculpture–Don Jarvis. master of properties–C. J. Rogers. m—[original score by Sigmund Romberg]. cost–Western Costuming Co., Richard Day, Erich von Stroheim. titles–Marian Ainslee, Erich von Stroheim. research asst-J . Lambert. l.p—Rudolph Christians/Robert Edenson (Andrew J. Hughes), Miss Du Pont [Patsy Hannen] (Helen Hughes), Maude George (“Princess”Olga Petschnikoff), Mae Busch (“Princess” Vera Petschnikoff), Erich von Stroheim (“Count” Sergei Karamzin), Dale Fuller (Maruschka), Al Edmundsen (Pavel Pavlich, the Butler), Cesare Gravina (Signor Gaston), Malvina Polo (Gaston’s Daughter [Marietta]), Louis K. Webb (Dr. Judd), Mrs. Kent (Mrs, Judd), C.J. Allen (Albert I, Prince of Monaco), Edward Reinach (Secretary of State of Monaco). Read more

Read more

Read more