From The Financial Times (July 4, 1975); this was the first of my two annual weekly film columns for that newspaper, replacing Nigel Andrews as his “deputy” while he was away.

A couple of asides: I had attended the press conference at Cannes for The Panic in Needle Park, and recall being disturbed by the heartlessness with which Didion and Dunne described their dispassionate and seemingly indifferent “research” about New York addicts. And on the matter of Mizoguchi, I would no longer define Yang Kwei Fei as any sort of “masterwork,” and am still making up my mind about Street of Shame.–- J.R.

To score or not to score

The Panic in Needle Park (X)

Berkeley 1

Diagnosis: Murder (A)

Plaza 2

Brewster McCloud (A)

Electric Cinema

Ugetsu Monogatari (X)

National Film Theatre

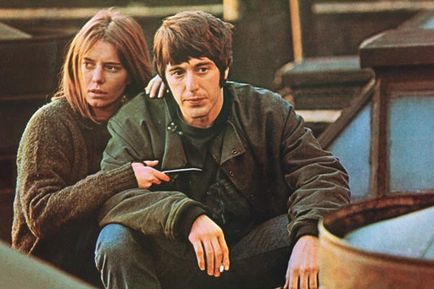

Of the two new releases on offer this week, The Panic in Needle Park is the better of an impossibly gloomy choice. Arriving here four years after its premiere at the Cannes Festival (where its female lead, Kitty Winn, was awarded Best Actress prize) — a delay apparently caused by its graphic depiction of heroin rituals being deemed unfit for local consumption — it offers at least one potential source of interest which was less evident in 1971: Al Pacino in his first major movie role.

Visibly undergoing a transition in techniques from stage to cinema acting, Pacino gradually gains in conviction as the film progresses. On first appearance, he is chewing a wad of gum so strenuously that he seems to be aiming his jaw movements at the back rows of the balcony; the part picks up some traces of subtlety and imagination after that, however, and if it never suggests any of the depths to be found in the Michael Corleone of the Godfather saga, it still brings a few charismatic touches to the character of Bobby, a small-time hood and addict who ambles about his desperate junky neighborhood like a prancing street monkey. But like the rest of the film, he is ultimately hampered as well as served by the dictates of a generalized, sociological authenticity so that he is never allowed to pass beyond the familiar boundaries of an all-too-familiar type, a problem equally limiting to his co-star.

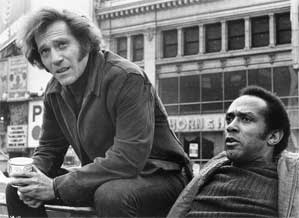

The movie’s director -– former fashion and advertising photographer Jerry Schatzberg – is a curious kettle of fish, and a particular cold and glassy-eyed breed of the species at that. Celebrated by one French critic for his “art of showing with complete lucidity the incredible depth of a secret wound,” he appears to be simultaneously detached and manipulative in all three of his movies to date, denying compassion with his right hand while abrasively pushing it with his left. Puzzle of a Downfall Child, his first, painted the milieu of his previous profession with avant-garde pretensions; Scarecrow, the third, offered a throwback to the literary trappings of Algren and Steinbeck, with fancy performances -– by Pacino and Gene Hackman -– and heavy doses of Tennessee Williams along the way.

Trying for a good deal less than either its forerunner or its successor, The Panic in Needle Park still has to contend with a handicap which faces virtually all films dealing with heroin addiction: how to keep its doomed characters dramatically interesting. The Man with a Golden Arm offered studio expressionism, jazz, and the star presences of Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak; more interestingly, The Connection confronted the audience with its own voyeurism regarding addicts while Ivan Passer’s Born to Win –- made the same year as The Panic, and regrettably unseen inthis country –- brought up the subversive possibility that its addict hero, George Segal, really liked what he was doing because it simplified all of life’s problems.

Seeking objectivity and distance in a love story about two addicts, Schatzberg treats his painful plot elliptically, cutting away from many of the obvious climaxes and moments of decision and usually catching his characters on the wing, making no attempt to plumb for motivations or arrive at moralistic conclusions. But somewhere along the way, his documentary impulse –- showing all of the hows and none of the whys –- becomes self-defeating. One is told that for several weeks before filming, Schatzberg screenwriters Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne (the husband-and-wife team who wrote the film adaptation of the former’s novel, Play It As It Lays) and the leading actors all lived on location at Broadway and 72nd Street on Manhattan’s West Side, studiously absorbing facts and atmosphere like anthropologists from another continent.

The fruits of these labors are evident throughout, bearing the earmarks of a conscientious case-study of all the descending circles in an addict’s inferno, from hustling to overdoses to betrayals in prison and back again. But none of them, alas, can tell us why we should care about the characters involved. To reach for that effect, the filmmakers have to throw their elliptical narrative and verisimilitude out the window by introducing a wholly sentimental incident — the accidental drowning of a newly-purchased puppy, when Bobby insists that he and his girl friend take their fixes en route on the Staten Island ferry, and the darling little pet conveniently scampers overboard right on cue.

***

At least one expedient drowning is at the center of Diagnosis: Murder, an utterly routine mystery thriller which pits detective Jon Finch against psychiatrist and murder suspect Christopher Lee for 90 minutes of semi-predictable guessing games. Since the plot of this shaky vehicle is all that it has to call its own, readers who intend to see the film regardless are advised to skip the following post-mortem.

The shame of it is that Philip Levene’s script does seem to furnish a few intriguing possibilities of moral ambiguity, none of which are realized in Sidney Hayers’ flat-footed direction. A double plot supplies us with two cripples: an unpleasant grouch in a wheelchair, married to Finch’s girl friend, whose helplessness winds up destroying the couple’s adulterous affair, and Lee’s wife (Dilys Hamlett), whom he secretly keeps in a virtually crippled state with heavy sedation, letting the police search for her corpse when she is reported missing, so that he can dispose of her afterwards and run off with his pretty secretary (Judy Geeson). In theory, then, our lack of sympathy for one victim should be played against our sympathy for the other. But in practice, Hayers keeps the two ploys separate and unconnected, focusing most of our attention on the machinations of Lee and Finch’s gratuitous investigation, and leaving the rest of the tale hanging.

***

A much better bet than either of the above movies could be found this week among the various offerings at the cinema clubs. Brewster McCloud, the late week-end movie at the Electric, qualifies to some degree as the first “real” Robert Altman film, made the year after the success of M*A*S*H gave him a chance to strike out on his own and experiment. In more ways than one, it provides a fascinating forecast and “first draft” of the exhilarating methods of his recent Nashville -– slated to open here late this year -– to which the lives of two dozen characters are energetically followed over the course of a few days in a brassy Southern capital.

The Southern capital in Brewster McCloud is Houston, Texas, dominated by the eerie edifice of the Astrodome, where the title hero (Bud Cort), with the help of his Guardian Angel (Sally Kellerman), is doggedly building wings with which to fly away. Intermixed with this fantasy is a mystery plot parodying Bullitt, a raving demagogic tycoon played by Stacy Keach, the first performance of Shelley Duvall (the remarkable heroine of Thieves Like Us) as a deadly Texas tease, and a host of other Altman regulars. Unlike the population of Nashville, these quirky characters don’t all quite belong to the same movie, but much of the zany humor and interest of Brewster –- along with its anthology of demented bird lore –- can be found in the various ways they don’t fit together.

***

If a masterpiece is what you’re after, however, Kenji Mizoguchi’s extraordinary Ugetsu Monogatari, at the NFT late show tonight, is obviously where you should be headed (although Jean Vigo’s lovely, lyrical L’Atalante, at the NFT Monday through Wednesday, is equally recommendable). Adapted from a novel by Veda Akinara set in 16th century Japan which has recently been brought out here in translation, this 1953 epic comprises the second in Mizoguchi’s string of late masterworks —The Life of Oharu, Sansho the Bailiff, The Crucified Lovers, The Empress Yang Kwei Fei, Shin Heike Monogatari, and Street of Shame -– with which he concluded his prolific career, and probably remains the best known of all of them.

A film about war and its aftermath, with haunting fantastic overtones, Ugetsu juxtaposes the stories of a village potter seduced by a phantom princess and that of a more ambitious man who virtually sacrifices his wife in order to become a samurai.The title –- roughly translatable as “Tales of the Pale and Silvery Moon After the Rain” -– perfectly evokes the mood: while Ugetsu is crammed with enough action to furnish six other spectaculars, its principal focus is less on the action itself and more on its consequences, the effects that war and love leave in their wake. Directed with incomparable beauty and control, it well deserves its place in the International Critics Poll conducted by Sight and Sound in 1962 and 1972, where it figured both times as one of the ten greatest films ever made.

Nigel Andrews is at the Berlin Film Festival.