From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977 (Vol. 44, No. 517). Over 30 years later, in my DVD column for Cinema Scope, I wrote, “Is it possible to find a picture acceptable only with its director’s commentary? Yes, if it’s Peter Bogdanovich’s clunky but interesting comedy about American moviemaking during the patent wars (1910-1915), prior to The Birth of a Nation, now that he’s finally had a chance to release it in black and white, as he originally intended, and recut it as well. Reviewing this when it came out…, I found its slapstick mainly irksome — not offensive, as it was to me in What’s Up, Doc?, where so many of the pratfalls, collisions, and smashups seemed to be about fatuous, narcissistic yuppies humiliating servants and carpenters, but pretty academic none the less…. It still looks academic, but hearing Bogdanovich explain where all the stories come from (mostly from Dwan, Ford, McCarey, and Walsh, with a curtain-closer from James Stewart) makes it somewhat more absorbing.” — J.R.

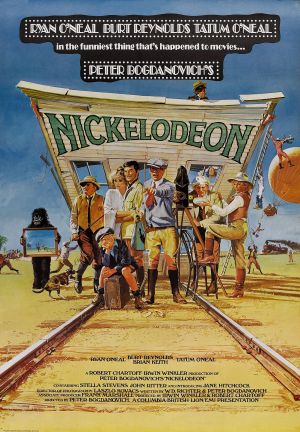

Nickelodeon

U.S.A./Great Britain, 1976

Director: Peter Bogdanovich

Chicago, July 30, 1910. Fleeing from a divorce court when he discovers that his client has an indefensible case, lawyer Leo Harrigan stumbles into H. H. Cobb, head of the independent Kinegraph Studios — fighting for survival against the Patents Company — who pays Leo for some of his story ideas and sends him to California to look after his business interests. Buck Greenway, a small-time performer from Florida, meanwhile arrives in New York to deliver a saddle, and after being hired to ride a horse in a stage show, is taken on by the Patents Company and also sent to California.

Leo arrives in Cucamonga, where he finds that Cobb’s director has abandoned the crew — including cameraman Franklin Frank, actress Marty Reeves and all-round assistant and driver Alice –- and Leo is enlisted as his replacement. While Leo prepares to shoot, Buck arrives and an extended fight ensues, after which Buck agrees to act in Leo’s movies. Kathleen Cooke — a dancer who has previously crossed the paths of Leo and Buck, accidentally exchanging her suitcase with each of theirs in the process — also joins the group as an actress. Buck proposes to her, and Leo is despondent when she accepts. Still in flight from the Patents Company, the crew take refuge at an ostrich farm where Buck and Kathleen are ‘married’ by an actor impersonating a priest. At a nickelodeon on Christmas Eve, 1913, they are shocked to discover that their short films have been intercut by Cobb into a mélange called Tuttle’s Muddle. Absconding with the print, they confront Cobb in Chicago and he fires all of them; they are then hired by Atlantic Pictures in Hollywood (except for Marty, who returns to Cobb). Six months later, after Leo is fired and the others quit, they begin to shoot a Western independently, but the Patents Company burns down their house, with all their films and equipment inside.

At the premiere of The Clansman in 1915 — where they meet Cobb, now married to Marty and talking of the birth of a new industry — Leo, Buck, Kathleen and Alice decide to resume filmmaking on their own.

Just after the world premiere of The Clansman (later retitled The Birth of a Nation), producer H. H. Cobb offers a short speech to his former employees that is clearly the ‘pay-off’ of Nickelodeon; the camera even tracks in closer during the scene, as it does during Sam the Lion’s climactic recollection in The Last Picture Show:

“Think of it. All those people going to see the pictures. And a lot of them can’t even talk American. They don’t have to because pictures are a language that everyone understands. . . And if you’re good, if you’re really good, then maybe what you’re doin’ is you’re giving ’em little tiny pieces of time . . . that they never forget”.

The fact that the last sentence in this declaration comes from a statement by James Stewart which serves as the epigraph for Bogdanovich’s collection of movie articles, Pieces of Time, only helps to emphasize how much of Nickelodeon — and Bogdanovich’s work as a whole — can be viewed as a continual recycling operation.

A considerable part of the commentary of Directed by John Ford, for instance, stems directly from the introduction to Bogdanovich’s interview book with Ford; and quite apart from all the studied pastiches which comprise the bulk of everything from Targets to At Long Last Love (nostalgic film references which differ radically from those of Godard, Rivette or even Truffaut by offering no critical distance or personal reading of film history, merely an attempt at simple regurgitation), the dearth of fresh material in Bogdanovich’s repertoire inevitably incurs the law of diminishing returns. Consequently, Nickelodeon — an obvious labor of love which by rights should have been Bogdanovich’s La Nuit Américaine –– lumbers across the screen with a leaden gait that makes even something like The Sting seem a triumph of personal expression.

The material in itself is scarcely in question: the final credits include a special acknowledgment to Allan Dwan and Raoul Walsh, and an appreciable amount of the film’s plot and details can be traced back to Bogdanovich’s interview book with Dwan — the whole manner in which Leo inadvertently becomes a director, his ‘initiation’ with the crew via a practical joke involving a rattlesnake and whisky, the skirmishes with the Patents Company, the ostrich farm, and a great deal more. Unfortunately, Bogdanovich has paid less heed to Dwan’s reiterated advice about directing in the same book: “Make the public work, If you do all the work for them, they sit there bored to death. Their imagination must be stimulated”. Borrowing directly from his own What’s Up, Doc?, Bogdanovich moves his three principals about like chess pieces (so that they improbably cross paths and accidentally switch suitcases), overdirects slapstick in a manner that ‘correctly’ dots every ‘i’ and crosses every ‘t’ (making the protracted fight between Leo and Buck more like an academic parody of Ford at his most tiresome than an hommage), and develops the ‘love interest’ as a set of mechanical ploys that makes it impossible for one to care who winds up with whom. Everything, in short, is reduced to a series of agile exercises which prevent any of his automatons from coming to life (including Jane Hitchcock, a charming newcomer whom one hopes to see again). The over-busy surface activity might seem so desperately willed because of its tendency always to gravitate towards ‘film history’, with history itself invariably taking a back seat — an attitude which helps to give cinephilia a bad name by appearing to imply that The Birth of a Nation is vastly more important than (say) the Civil War. One of the many consequences of this is a treatment of film history that seems weirdly ahistorical, so that the ‘wild man’ who supplies Cobb with outlandish story ideas is dressed in a way that suggests Keaton, and a stuttering crew member –- a perfect example of a running gag used mechanically — comes across more like a refugee from a Fifties Ford Western than a character identifiable with the period. This tendency culminates in the disquieting flatness of the climactic Clansman premiere, which makes it difficult for an uninformed spectator to understand how or why Griffith’s film had the impact it did in 1915. Once again, the sources appear to be impeccable, and some of this sequence (including an effectively Fordian long shot of Griffith appearing on stage to waves of applause) seems indebted to Karl Brown’s memorable account of it in Adventures with D. W. Griffith; yet overall, the period detail registers as stilted and obligatory. An engaging notion in the script — that movie-making begins with thinking up wild ideas, for which one then has to dream up narrative excuses — ultimately tends to backfire, perhaps because the ‘narrative excuses’ are often more noticeable in Nickelodeon than the ‘wild ideas’ (which themselves usually come across more like ghoulish transplants than inspirations). Indeed, the virtually total rejection by Bogdanovich of anything that exists beyond the boundaries of certified (and ossified) movie myth may help to explain the curious sterility of Nickelodeon in relation to its fascinating subject and sources.