From the Chicago Reader (March 22, 1991). — J.R.

One of the most underrated films of 1990, representing Corman’s directorial comeback after 19 years, adapts Brian Aldiss’s intellectually ambitious novel about a 21st-century scientist (John Hurt) who finds himself in Geneva in 1816, where he meets Mary Shelley (Bridget Fonda) and her famous fictional creations, Frankenstein and his monster. Far from a total success (and apparently hampered by some studio recutting), this metaphysical reflection on technology with SF and monster-movie trimmings is packed with wit, originality, and eccentricity. If you missed it the first time around — which wasn’t hard to do, given its perfunctory promotion and distribution — you should definitely catch it. With Raul Julia and Michael Hutchence. (Music Box, Monday, March 25)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1990), tweaked in April 2014. This film is finally available now in a DVD that does its visuals (and John Alton’s cinematography) something approaching full justice. One of the juicier actors in this action romp that I should have mentioned is Arnold Moss, seen in the first still below with Robert Cummings. — J.R.

Along with James Whale’s The Great Garrick, this 1949 melodrama about the French Revolution, also known as The Black Book, is one of the few period pictures that qualify as film noir; Anthony Mann directed it with sumptuously arty chiaroscuro (cinematography by John Alton). With the two leads (Robert Cummings and Arlene Dahl) periodically steering it in the direction of camp, this film is loads of fun. Richard Basehart also stars (as Maximillian Robespierre, no less); Philip Yordan and Aeneas MacKenzie coscripted. 88 min. (JR)

Read more

From the May 1, 1998 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

High-grade infotainment, even though it’s directed by Barbara Kopple (Harlan County U.S.A., American Dream), this is an “intimate” documentary of Woody Allen’s 1996 European tour with his Dixieland band, filmed at Allen’s instigation by his own production company, with Allen rather than Kopple retaining final cut, though it’s made to seem that Allen went along with the scheme rather than dreamed it up himself. On the plus side, it shows him at his most serious, as a dedicated (and better than average) clarinetist performing with an OK New Orleans-style band, and it provides some generous insights into his psychic background when his unsupportive parents greet him back in New York at the end. It also furnishes plenty of evidence of his outsize European reputation as he’s mobbed by fans in Paris, Madrid, Vienna, Venice, Milan, Bologna, Turin, Rome, and London. The controlled casualness of Allen’s breakfast patter with his young wife, Soon-Yi Previn, which tends to foster the pretense that a camera crew isn’t around, seems to balance candor with concealment, just as his fictional features do. All in all, I found this more absorbing than Everyone Says I Love You and Deconstructing Harry, though it certainly isn’t a patch on Manhattan Murder Mystery. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 8, 2005). Nine years later, having recently reseen this fabulous film on Blu-Ray (a beautiful job from Warners, with many enticing extras), I would currently maintain that what I formerly called the “key cinematic sources” should probably have been called key cinematic cross-references — to which one should add Raul Ruiz’s City of Pirates for its own shot which purports to be a view of someone’s teeth from the inside of his mouth. — J.R.

Tim Burton finally fulfills the promise of Beetlejuice (1988) with this imaginative masterpiece, adapted from the 1964 children’s book by Roald Dahl but characterized by Burton’s special feeling for color, architecture, and nightmarish dislocation. Adapted by John August, this schematic fable of five children invited to tour a mysterious candy factory is well served by the surrealistic design, Johnny Depp’s mannerist performance as the androgynous chocolate tycoon Willy Wonka, and the deft digital wizardry that multiplies actor Deep Roy into the entire workforce of the Wonka factory, performing crazed production numbers. (Among the key cinematic sources here are the ice cream factory in the Eddie Cantor musical Kid Millions and the hyperbolic The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T.) There’s a streak of moralism, but it never becomes as sticky as the candy because the invention never flags. Read more

From the February 1, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Here’s one very sick and messed-up movie. As misogynistic as anything I’ve seen in ages, it’s tricked up with enough fancy cinematography (by Guy Dufaux) to guarantee it sub-Hitchcockian credentials of the sort that some reviewers eagerly hand out to Brian De Palma. A surveillance specialist for the British secret service (Ewan McGregor) who’s haunted by the loss of his wife and little girl years earlier obsessively tracks a psychopathic murderer (Ashley Judd) across the U.S. The first couple of times he and we watch her take her clothes off through his surveillance equipment, grisly murders follow; after that we get more grisly stuff but less cheesecake. Writer-director Stephan Elliott (The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert), adapting a novel by Marc Behm, shows how much he likes The Conversation, Bob Rafelson’s Black Widow, and Basic Instinct by serving up pastiches of them all and hoping everything somehow fits together. (To all appearances, the plot was resolved with a coin flip.) According to this movie’s view of femininity, Genevieve Bujold as a reform school official is womanly, therefore evil, and K.D. Lang as a secret service contact is androgynous, therefore OK. Read more

From the August 15, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

If you thought virtual-reality thrillers and spin-offs of The Silence of the Lambs had run their course, guess again. Jennifer Lopez, who looks great in a rubber suit, keeps putting one on in order to enter the unconscious of a serial killer/mad scientist-genius (Vincent D’Onofrio) and discover where he’s hidden his latest victim; meanwhile, hot and bothered FBI agent Vince Vaughn is also on the case. There’s almost no plot here and even less character — just a lot of pretexts for S-M imagery, Catholic decor, gobs of gore, and the usual designer schizophrenia. Tarsem Singh, a specialist in commercials and music videos (assuming one can distinguish between the two), directed a script by Mark Protosevich, and Marianne Jean-Baptiste costars as the voice of reason, present to offer an occasional change of pace. 107 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1990). — J.R.

A highly intriguing if not always fully successful first feature (1990) by independent writer-director Hal Hartley, shot in his hometown on Long Island, gives us, among other characters, a mechanic mistaken for a priest (Robert Burke) returning from a prison sentence, a politically alienated teenager (Adrienne Shelly), and the teenager’s mercenary redneck father (Christopher Cooke). Fantasies about global annihilation obsess the teenager, fantasies about money obsess her father, and fantasies about a pair of murders apparently committed by the mechanic obsess almost everyone else. The unvarnished quality of some of the acting limits this effort in spots, but the quirky originality of the story, characters, and filmmaking keeps one alert and curious. With Julia McNeal, Mark Bailey, and Gary Sauer. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1994). Whatever it is, “avant-garde cinema” it isn’t. — J.R.

This gory, postmodernist fruit salad may be the most misogynistic piece of noir since Body Heat, though as in Basic Instinct a certain amount of giddy dominatrix worship — in this case focused on Lena Olin as an evil mobster — gets mixed into the brew of producer Hilary Henkin’s script. It’s the sort of fancy-pants movie that can have a wealthy hoodlum (Roy Scheider) threatening its hero (Gary Oldman), a crooked cop on the take, by recounting an anecdote about Robert Lowell. As in The Grifters, another exercise in Hollywood noir directed by a non-American (here it’s the Hungarian Peter Medak, who works mostly in England), one can’t easily tell whether this is taking place in the 40s or half a century later; but with so many baroque plot moves and narrative devices, and so much self-consciously ornate dialogue and voice-over narration, you’re not supposed to notice or care. The film certainly held me, and even fooled me in spots (when it wasn’t simply confusing), but when the whole thing was over I felt pretty empty. It would be facile to say it substitutes style for content; actually, it substitutes stylishness for style. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1992). Reseeing the film recently in a splendid new Blu-Ray edition from Twilight Time, I now regard this as Cy Endfield’s greatest film — and one the best war films ever made, a magnificent epic that succeeds on many levels. — J.R.

The only commercial hit made by Cy Endfield, the neglected, blacklisted American writer-director who emigrated to England in the 50s — an epic and visually quite impressive account of an attack by 4,000 Zulu warriors on 105 British soldiers in Natal in 1879. While the incident is recounted wholly from the British viewpoint, the film is not racist, as some charged when it was released in 1964. Reflecting Endfield’s career-long refusal to plumb his characters’ motivations, it presents all the events at face value, not even delving directly into the causes of the Zulu attack. (Reportedly, Endfield tried to compensate in the script he wrote for the 1979 Zulu Dawn, directed by Douglas Hickox.) While it might be argued that Endfield’s greatest work (i.e., Try and Get Me!) shows a political and social lucidity about class divisions and group behavior that is only hinted at here, the handling of action and spectacle and the direction of actors are truly masterful. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1991). — J.R.

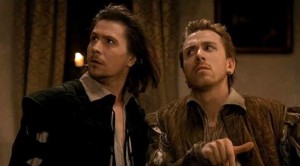

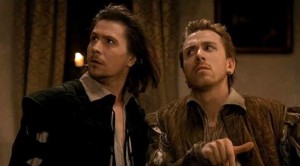

Tom Stoppard freely adapts, directs, and all but destroys his own enjoyable and provocative absurdist play about two minor characters in Hamlet, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Gary Oldman and Tim Roth), victims of a drama taking place in the wings that they can neither understand nor control. Critic Kenneth Tynan suggested that the play may have been the first to use another play as decor; if so, then the film uses two plays — Hamlet and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead — and often the consequences are even more confusing than Stoppard could have intended. I can’t imagine a play less suited for a film adaptation, although Stoppard might have turned this to his advantage had he confronted that paradox. Instead he tries to open up a work that depends upon a sense of claustrophobic limbo, then undermines that approach by focusing the camera so tightly on the characters that he muddles our sense of spatial continuity. In Stoppard’s play, Hamlet is something semi-inexplicable that happens to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, while the screenplay turns it into something they’re obliged to chase after; unfortunately, Stoppard’s sense of film is so inferior to his feeling for the stage that he makes the same compromises and reductions a Hollywood hack might have brought to the material. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1991). — J.R.

A delightful if fanciful treatment (1991) of the events leading up to the romance between assertive George Sand (Judy Davis) and prudish Frederic Chopin (Hugh Grant) — roughly from 1836 to 1838 — that also involves such artists as Alfred de Musset (Mandy Patinkin), Franz Liszt (Julian Sands), and Eugene Delacroix (Ralph Brown), as well as Liszt’s lover and Sand’s friend Marie d’Agoult (Bernadette Peters) and Sand’s former lover Felicien Mallefille (Georges Corraface), a tutor to her children. James Lapine, best known as the director and librettist of Stephen Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park With George and Into the Woods, fluidly directs a lively script by his wife Sarah Kernochan, and a generous number of piano pieces by Chopin and Liszt are smoothly integrated into the story. Especially good in the cast are Davis (adept in translating Sand’s boldness in dress and manner into body language) and Anna Massey as her mother. PG-13, 108 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

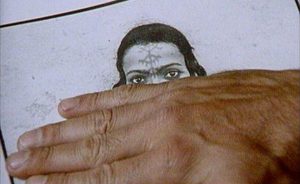

From the February 1, 1992 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

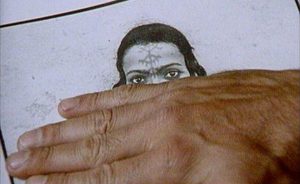

A fascinating 1988 film essay about photography by Harun Farocki, one of Germany’s most interesting independent filmmakers. Farocki combines the freewheeling imagination of Chris Marker with the rigor of Alexander Kluge, and his materialist approach to editing sound and image suggests both Fritz Lang and Robert Bresson. Central to the argument of this film are some aerial photographs of Auschwitz taken by American bombers looking for factories and power plants and missing the lines of people in front of the gas chambers — which are contrasted with Nazi photographs and images drawn by an Auschwitz prisoner, Alfred Kantor. Farocki’s provocative reflections on these and related matters and his highly original manipulation of music make this an excellent introduction to his work, which has seldom been visible in this country. In German with subtitles. 75 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

What a pleasurable experience it is to pass directly from a slew of end-of-the-year screeners, most of which I can’t watch to the end, to a 1933 King Vidor opus that still isn’t commercially available on DVD. (According to Scott Simmon, Raymond Durgnat’s coauthor on King Vidor, American [1988], this is Vidor’s most underrated movie; Durgnat opts for Ruby Gentry.) A characteristic virtue of this character-driven adaptation of a Phil Stong novel set in farming country is a shot devoted to a dog wandering into a Sunday morning church service during the sermon, noticing that the place is full, and gradually sitting down under one of the pews. It’s the sort of inessential detail that I wouldn’t expect to find in any contemporary movie. I have no way of knowing whether or not this was scripted, but considering how little it has to do with the plot, I suspect it wasn’t—that Vidor happened on such a shot as an afterthought. Apart from the economy of 30s features, this sort of meandering poetry seems increasingly rare in today’s movies. [12/20/08] Read more

As a fan of the directorless Theater Oobleck dating all the way back to its second show in Chicago (David Isaacson’s riotous Three Who Dared: A Play on the Movies, in June 1988), with particularly fond memories of Jeff Dorchen’s The Slow and Painful Death of Sam Shepard (December 1988) and Ugly’s First World (October 1989) as well as Mickle Maher’s When Will the Rats Come to Chew Through Your Anus? (January 1990), I regret having somehow lost touch with their singular repertory of literary and political shotgun marriages in recent years. A recent visit to Dorchen’s brilliantly excessive Strauss at Midnight at the the Chicago DCA Theater (66 E. Randolph), which runs through July 19, reminded me of how much heat and liberating anger and laughter they can generate.

This play has something to do with Saul Bellow (Isaacson), posthumously still tainted by his former association with Allan Bloom (Troy Martin), and, through Bloom, with Leo Strauss (David Shapiro), condemned to a hell in which he has inhabit the same quarters as Neil Simon’s Odd Couple (Brian Nemtusak and H.B. Ward doing fine, surreal spinoffs of Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau), not to mention Niccolo Machiavelli (Scott Hermes) and In the Heat of the Night‘s Virgil Tibbs (D’wayne Taylor). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1988). — J.R.

Andrei Konchalovsky’s follow-up to his 1967 Asya’s Happiness was a much safer literary adaptation of a Turgenev novel about a cuckolded member of the Russian aristocracy of the mid-19th century who is the son of a servant girl and a nobleman and who struggles unsuccessfully to find a place for himself in society. Ambitious but rather slow, using a variety of camera techniques that suggest the influence of the French New Wave, this is a respectable if unexciting work by a talented filmmaker. Attractively filmed in color, and certainly more interesting than A Handful of Dust as a treatment of fading aristocracy, it nonetheless lacks the sense of discovery conveyed in Konchalovsky’s best Soviet and American work (1969). (JR)

Read more

Read more