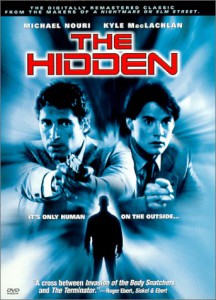

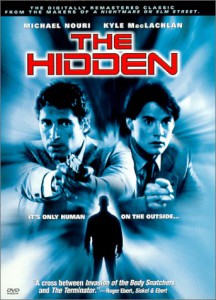

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1987). — J.R.

Michael Nouri and Kyle MacLachlan (Dune, Blue Velvet) star in this 1987 SF crime thriller, directed by Jack Sholder, about a police detective investigating a series of mysterious crimes who discovers that the perpetrators are all inhabited by an alien life form. Despite its reputation as a sleeper, this isn’t much more than a capably directed version of a film we’ve already seen many times before: some well-executed car chases and efficient acting (including proof that MacLachlan can be weird without David Lynch), but not much development of the familiar possession theme a la Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters. Unfortunately, many of the most intriguing details — such as the alien’s taste for loud pop music — are left hanging rather than fleshed out, and the film eventually reduces itself to mechanical (if well-crafted) action sequences. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 10, 1990). Even though this is favorable, I think I underestimated the achievement of this first feature; reseeing it a quarter of a century later, in preparation for a very enjoyable public Skype conversation with Whit Stillman held at the Gene Siskel Film Center, it looked much better and much richer, and the tenderness shown towards almost all of the characters is indelible. — J.R.

Whether it’s “accurate” or not, Whit Stillman’s crafty independent feature about wealthy Park Avenue teenagers and a middle-class boy who joins their ranks over one Christmas vacation is certainly well imagined, and impressively acted by a cast of newcomers (including Carolyn Farina, Edward Clements, Christopher Eigeman, Taylor Nichols, and Elizabeth Thompson). The simple but offbeat form of the film — which concentrates mainly on a series of social gatherings among a circle of friends, separated by fade-outs — has its awkward moments, but the charm of the actors and the wit and freshness of the dialogue (which touches on such subjects as Jane Austen, romance, and class consciousness) keep one interested (1990). (Fine Arts)

Read more

Read more

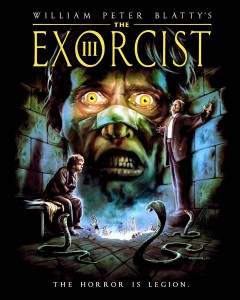

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1990). — J.R.

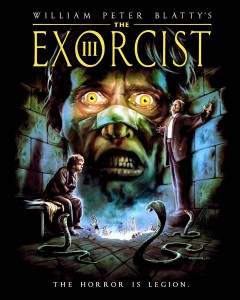

An official sequel to the original story — that is, a movie that begins where The Exorcist, rather than Exorcist II: The Heretic, left off. William Peter Blatty, author of the original novel and its screen adaptation, wrote and directed this 1990 feature, adapting his own novel Legion, and while he apparently lacks the means to make this work at the level of its predecessor — there’s too much mumbo jumbo in the dialogue and not enough continuity in the story — his decision to hold back on visible gore and depend mainly on camera and actors (especially Brad Dourif as a mental patient possessed by Satan) to suggest the full range of his horrors frequently pays off. And even when it doesn’t work, the film is never boring. The cast also includes George C. Scott, Ed Flanders (particularly good as a likable priest), Jason Miller, Scott Wilson, Nicol Williamson, Nancy Fish, Lee Richardson, Viveca Lindfors, Zohra Lampert, and Barbara Baxley; Gerry Fisher is the cinematographer. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 2001). — J.R.

John Ford, Henry Hathaway, and George Marshall directed the individual episodes of this 1962 triptych about the settling of the American frontier, originally released in Cinerama. The Ford episode, about the Civil War, is uncommonly good; the rest is expendable, especially without the three-screen process. With Carroll Baker, Henry Fonda, Gregory Peck, George Peppard, Carolyn Jones, Eli Wallach, Robert Preston, Debbie Reynolds, James Stewart, John Wayne, and Richard Widmark. 155 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

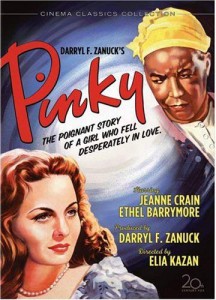

From the Chicago Reader (January 9, 1990). — J.R.

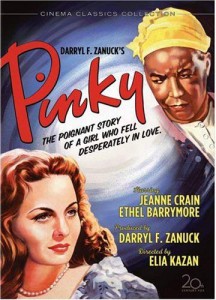

John Ford claimed to be sick in order to get out of directing this drama about Jeanne Crain as a white-skinned black woman passing for white who returns to her family in the deep south. Elia Kazan took over the production, and the results are uneven, though fitfully interesting. Ethel Waters has a commanding presence as Crain’s mother, and Ethel Barrymore and William Lundigan also star. A companion piece of sorts to Kazan’s previous Gentleman’s Agreement, in which Gregory Peck, a Jew, plays a gentile impersonating a Jew in order to test anti-Semitism. Here it’s Crain, a white woman, playing a black woman who passes for white — an even more bogus way of dealing with the issues involved (1949). (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the July 8, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

JOHN HUSTON & THE DUBLINERS

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Lilyan Sievernich.

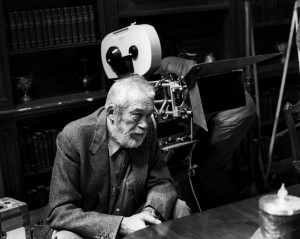

The on-location production documentary, a movie chronicling the shooting of a movie, is a fairly recent phenomenon, although its equivalent in print has been around much longer. (For instance, Micheal MacLiammoir’s Put Money in Thy Purse, about Orson Welles’s Othello, and Lillian Ross’s Picture, about John Huston’s The Red Badge of Courage, were both published in 1952.) One usual difference between the written and the filmed reports is that the latter tend to be inside jobs financed by the producers of the features in question, and consequently are promotional in nature rather than critical: Chris Marker’s short feature about the making of Ran and Ron Mann’s documentary about the making of Legal Eagles are two recent examples, and Lilyan Sievernich’s hour-long account of John Huston shooting The Dead belongs in this category. Yet there are a few things about Sievernich’s film that make it rather special.

Huston was 82 and very close to dying when he made The Dead, and everyone connected with the film was acutely aware of it. He directed from a wheelchair, was hooked up to an oxygen machine for his emphysema, and generally viewed the actors on the set from a TV monitor. Read more

I am reprinting the entirety of my first and most ambitious book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, New York: Harper & Row, 1980) in its second edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) on this site in eleven installments. This is the eleventh and last.

Note: The following index to Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980) cannot be used here for its pagination in relation to this particular web site, but the links provided lead directly to the relevant passages online.

Another note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

Directions for Use

An attempt to extend the usefulness and reduce the elitism of the standard index, in which the reader is enabled to trace certain connections and to discover or rediscover the traces of certain people, places, films, and other cultural artifacts, in motion and in circulation, whether cited or merely evoked in the text. A few supplementary bibliographical suggestions are also included.

A

Aaron, Judge Edward, 142 , 192

A Bout De Souffle. See Breathless

Academy Awards, 118 , 124

Advent screens, ix , 118 , 147 , 174

Advertising, x , 7 -8, 10 , 18 , 29 , 35 , 40 , 43 , 52 -53, 55 , 58 , 60 , 63 , 68 , 77 , 85 , 93 , 98 -99, 101 , 108-120 , 122 , 123 -124, 127 , 142 -143, 144 , 149 , 158 , 177 . Read more

I am reprinting the entirety of my first and most ambitious book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, New York: Harper & Row, 1980) in its second edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) on this site in eleven installments. This is the ninth.

Note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

Station Identification II

Yes, I need the Conquistador; and yes, I mistrust and sometimes despise him. At eight and ten, while watching On Moonlight Bay, I knew that I needed him, and I loved him, too; I’m sure that I even loved my servitude. Now I question how well he fulfilled his duties as a foster parent. I can’t deny that he kept me entertained and even busy, but whether he’s worthy of the sort of unquestioning admiration due to, say, Nigger Jim is a different matter. Right now I’d say that it was Uncle Remus who came closer to describing—or executing—his peculiar talents.

Now there was a traumatic experience. Walt Disney’s Song of the South , according to my real parents, was the first film they ever took me to (probably during its initial run at the Princess, April 8–11, 1947, not long after I turned four and less than a year after Bo taught me how to read). Read more

I am reprinting the entirety of my first and most ambitious book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, New York: Harper & Row, 1980) in its second edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) on this site in eleven installments. This is the fifth.

Note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

Station Identification I

The Conquistador has a heart condition. Despite the recent successes of some of his biggest exploits, the mounting fortunes, his exhaustion becomes increasingly apparent, showing up in the lines on his face, the heaviness of his stride. Out of respect to his power, position, and age, we breathe not a word about his deterioration, act as if everything is as it should be. Obediently we tote his luggage along with our own, slow our paces to his, and gaze with enchantment at the passing scenery.

Getting from here to there is all the Conquistador really cares about, and tough luck for whatever—and whoever—happens to be occupying the intervening spaces. Think of a country, an audience, a movie, a dream that is perpetually en route, refusing to stop anywhere and settle for a while; think of a life on the march that promises adventure, discourages reflection, and delivers the excitement of perpetual motion. Read more

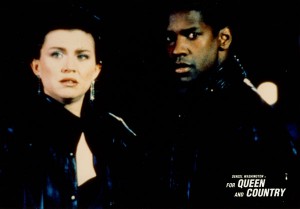

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1989). — J.R.

Denzel Washington (Cry Freedom) stars in this new British thriller by Martin Stellman about a black veteran who returns from nine years in the British army to encounter poverty and racism in London. A West Indian by birth, he finds that he is unable to renew his passport because of a new law, and a series of other misfortunes and injustices gradually force him against his will into a life of crime. Effective radical agitprop, relentless in its anger, this film is more outspoken about contemporary racism in England than any other feature that comes to mind; the story is structured a bit like a Warner Brothers thriller of the 30s, and the script (by Stellman and Trix Worrell), direction, and performances all give it a powerful impact. With George Baker, Amanda Redman, Dorian Healy, Geff Francis, and Bruce Payne. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 17, 1990). — J.R.

PUMP UP THE VOLUME

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Allan Moyle

With Christian Slater, Samantha Mathis, Scott Paulin, Ellen Greene, Annie Ross, Cheryl Pollak, and Andy Romano.

It’s hard to talk seriously about the 60s today, because TV and a lot of assholes have almost ruined it. When I taught film courses in southern California in the mid-80s, I was appalled to discover that college students thought of the 60s as a traumatic, troubled period — a time characterized by young people losing their way, freaking out on bad acid trips, denouncing their parents, getting killed in Vietnam, and protesting the way American society was being run and abjectly failing at it. For students of the 80s, the golden age was the repressive, bland, stultifying 50s, when staunch family and property values were both firmly in place — the mythical past that Uncle Ronnie and all his furry friends comfortingly evoked.

Many of these students didn’t realize — and some of them still don’t — that the 60s was a more prosperous period than the 50s, economically as well as spiritually. Some people actually had fun at demonstrations and on hallucinogens, and they often accomplished and learned important things in the process. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1995). — J.R.

Linda Fiorentino proudly and impressively mounts the throne of bitch noir goddess in this 1994 feature directed by John Dahl (Red Rock West) from a Steve Barancik script. There’s really not much to keep the picture going apart from her unbridled ruthlessness, but there’s plenty of fun to be found in that delectation alone. After goading her husband to pull off a dangerous drug deal and then running off with the loot, leaving him to the mercies of a deadly loan shark, she picks up another unsuspecting (if ambitious) fall guy in a small-town bar and schemes some more. Unlike the classic noirs, this is grounded in neither a recognizable social reality nor a metaphysical sense of doom — just a lot of sexy attitude, humping, and heavy breathing. But it’s an entertaining and caustically humorous thriller if you like that sort of thing. With Bill Pullman, Bill Nunn, Peter Berg, and the ever-reliable J.T. Walsh. 110 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

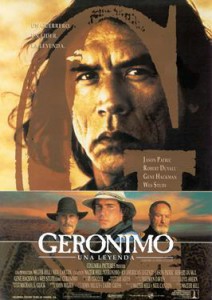

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1993). This film will be out soon on a Blu-Ray from Twilight Time. — J.R.

Like Unforgiven, this is conservative revisionism with a rare bitterness of tone (1993). The subject here is the underhanded treatment of Apaches by the U.S. government, and perhaps because of where it’s coming from it’s a lot more convincing as history than liberal revisionist westerns like Dances With Wolves. Though the director is Walter Hill, the dominant personality is John Milius, who wrote the story and collaborated on the script with Larry Gross, and despite some narrative stodginess in spots, Milius’s sense of warrior nobility and his talent for writing juicy parts for actors serve the picture well. Recounting the final rebellion and surrender of Apache leader Geronimo in the 1880s, the film offers especially fine performances by Robert Duvall as a grizzled Apache scouter, Cherokee actor Wes Studi as Geronimo, and Jason Patric as a U.S. cavalry lieutenant assigned to bring Geronimo in, and Gene Hackman, Matt Damon, and Kevin Tighe are more than adequate in less showy parts. The Utah settings are spectacular, and the music is by Ry Cooder. (JR) Read more

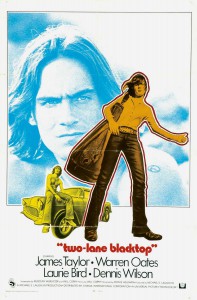

From the Chicago Reader (February 23, 2001). — J.R.

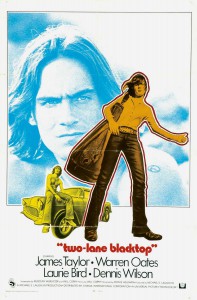

This exciting existentialist road movie by Monte Hellman, with a swell script by Rudolph Wurlitzer and Will Corry and my favorite Warren Oates performance, looks even better now than it did in 1971, although it was pretty interesting back then as well. James Taylor and Dennis Wilson are the drivers of a supercharged ’55 Chevy and Oates is the owner of a new GTO (these nameless characters are in fact identified only by the cars they drive); they meet and agree to race from New Mexico to the east coast, though side interests periodically distract them, including various hitchhikers (among them Laurie Bird). (GTO hilariously assumes a new identity every time he picks up a new passenger, rather like the amorphous narrator in Wurlitzer’s novel Nog.) The movie starts off as a narrative but gradually grows into something much more abstract — it’s unsettling but also beautiful. 101 min. A 35-millimeter print will be shown; film scholar Hank Sartin will introduce the film and give a lecture after the screening. Gene Siskel Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Tuesday, February 27, 6:00, 312-443-3737.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 21, 1988). — J.R.

HIGH HOPES

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Mike Leigh

With Philip Davis, Ruth Sheen, Edna Dore, Philip Jackson, Heather Tobias, Leslie Manville, David Bamber, Jason Watkins, and Judith Scott.

One of the most interesting things about Mike Leigh’s up-to-the-minute bulletin from Thatcher England is its title. Because this wonderful English movie is partly a comedy, and because it’s very much about the way that Londoners live nowadays, one would assume a title like High Hopes is ironic. Among most of my English friends, the expectations currently expressed about their country’s future couldn’t be much lower; and at first glance, there’s nothing in this movie to contradict their pessimism.

But take a second look at Leigh’s movie — which is sharp and funny and broad enough to warrant it — and you might find some reason for revising this opinion. England is after all a country of survivors, and one of the best ways of surviving in extreme situations (say, the London blitz) is to assume the worst and start from there. That’s what the leading characters and heroes of High Hopes do, a very charismatic, funky post-hippie couple named Cyril (Philip Davis) and Shirley (Ruth Sheen). Read more