Chantal Akerman’s greatest film — made in 1975 and running 198 minutes — is one of those lucid puzzlers that may drive you up the wall but will keep you thinking for days or weeks. Delphine Seyrig, in one of her greatest performances, plays Jeanne Dielman, a Belgian woman obsessed with performing daily rounds of housework and other routines (including occasional prostitution) in the flat she occupies with her teenage son. The film follows three days in Dielman’s regulated life, and Akerman’s intense concentration on her daily activities — monumentalized by Babette Mangolte’s superb cinematography and mainly frontal camera setups — eventually sensitizes us to the small ways in which her system is breaking down. By placing so much emphasis on aspects of life and work that other films routinely omit, mystify, or skirt over, Akerman forges a major statement, not only in a feminist context but also in a way that tells us something about the lives we all live. In French with subtitles. (JR) Read more

LE JEU DE L’OIE

From Rouge No. 2 (2004). — J.R.

| Snakes and Ladders (Le Jeu de l’Oie: La Cartographie, short, France, 1980) |

|

Eye Candy [THE VERTICAL RAY OF THE SUN]

From the Chicago Reader (September 14, 2001). — J.R.

The Vertical Ray of the Sun ***

Directed and written by Tran Anh Hung

With Tran Nu Yen-khe, Nguyen Nhu Quynh, Le Khanh, Ngo Quang Hai, Tran Manh Cuong, and Chu Ngoc Hung.

Last spring I was in Austin, Texas, on a film-festival panel about film festivals with the editor of a film magazine who’s also the author of a book on film festivals. “I don’t like foreign films or academic films,” he told me, a declaration that stumped me at first because it raised two vexing questions: (1) Why link “foreign films” and “academic films” as if the two had something intrinsic in common? (2) Had he seen at least one film from every foreign country in the world that produced movies and made his judgment on that basis?

After pondering other things he said, I came up with what I believe were the correct answers to both questions. (1) Foreign films and academic films were linked for him because both obliged him to think. (2) Of course not; what he meant by “foreign” was simply “not American.” Put these premises together and it’s clear he was saying he didn’t like movies that made him think, which is what non-American movies did — apparently even Bavarian porn, Italian splatter fests, and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Read more

The Lady Without Camelias

Perhaps the most unjustly neglected of Michelangelo Antonioni’s early features, La Signora Senza Camelie (1953) is a caustic Cinderella story about a Milanese shop clerk (Lucia Bose) who briefly becomes a glamorous movie star. One of the cruelest and most accurate portraits of studio filmmaking and the Italian movie world that we have, it’s informed by a visually and emotionally complex mise en scene that juggles background with foreground elements in a choreographic style recalling Welles at times. Though it’s only Antonioni’s third feature, and its episodic structure necessitates a somewhat awkward expositional method, this is mature filmmaking that leaves an indelible aftertaste. In Italian with subtitles. 105 min. (JR) Read more

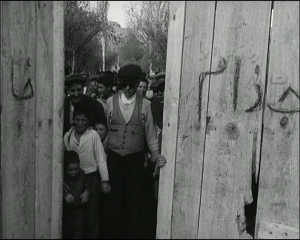

A Moment of Innocence

From the Chicago Reader (April 4, 1997). — J.R.

This is one of the best features (1996) of the prolific and unpredictable Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a dozen of whose films are showing at the Film Center this month. It’s also one of his most seminal and accessible — a reconstruction of a pivotal incident during his teens. At the time the shah was in power, and Makhmalbaf was a fundamentalist activist. He stabbed a policeman, was shot and arrested, and spent several years in prison. Two decades later, his politics quite different, Makhmalbaf was auditioning people to appear in his film Salaam Cinema, and among them was the policeman, now unemployed. The two of them wound up collaborating on this film, which tries to reconcile their separate versions of what happened with separate cameras. No doubt it was prompted in part by Abbas Kiarostami’s remarkable Close-up (1990), another eclectic documentary that reconstructs past events — a hoax that involved Makhmalbaf himself — with two cameras (showing at the Film Center on April 24). But this is no mere imitation; it’s a fascinating humanist experiment and investigation in its own right, full of warmth and humor as well as mystery. The original Persian title, incidentally, translates as “Bread and Flower.” Read more

The House Is Black

From the Chicago Reader (March 7, 1997). Note: The film is now available with English subtitles. — J.R.

The most powerful Iranian film I’ve seen is this 22-minute black-and-white 1962 documentary made by Forugh Farrokhzad (1935-1967), commonly regarded as the greatest 20th-century Persian poet. It’s her only film and its subject is a leper colony in northern Iran. Part of what’s so special about it is its seamless adaptation of the techniques of poetry to the techniques of film, in which framing, editing, sound, and narration all play central roles. At once lyrical and extremely matter-of-fact — without a trace of sentimentality or voyeurism, yet profoundly humanist — Farrokhzad’s view of everyday life in the colony (children at school and at play, people eating, various medical treatments) is spiritual, unflinching, and beautiful in ways that have no apparent Western counterparts; to my eyes and ears, it registers like a prayer. This extremely rare film has never been subtitled, but at a symposium on Farrokhzad’s life and work, Chicago filmmaker Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa will follow a video screening of The House Is Black with a discussion in English. Preceding this will be the premiere of a video documentary in English that I haven’t seen, Mansooreh Saboori’s I Shall Salute the Sun Once Again, and a discussion with Saboori. Read more

Monsieur Hire

From the June 1, 1990 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

A heartbreaking French melodrama (1990), adapted from a novel by Georges Simenon (Les fiancailles de M. Hire) about a shy and reclusive tailor (Michel Blanc) obsessively spying on a beautiful neighbor (Sandrine Bonnaire), who discovers and is touched by his voyeuristic interest. The plot also involves the mysterious death of a girl in the neighborhood. Paradoxically, director Patrice Leconte, who collaborated with Patrick Dewolf on the script, filmed this elegant, affecting, and highly claustrophobic chamber piece in ‘Scope; Michael Nyman contributed the haunting score. With Luc Thuillier and Andre Wims. 88 min. (JR)

The Shooting

This was reviewed at one point or another for the Chicago Reader. — J.R,

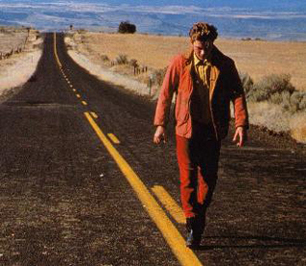

Monte Hellman’s remarkably hip avant-garde western (1967) was sold straight to television in the U.S.; while overseas it became a standard reference point for cinephiles, here, alas, it remains a cultist legend that’s never received the attention it deserves. A provocative and often witty head scratcher, it stars Jack Nicholson (who also produced) as a hired gun and Warren Oates, both at their near best, along with Will Hutchins and Millie Perkins. With its existentialist approach to treks through the wilderness, this is one of the key forerunners of Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man. (JR)

Dogma

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1999). — J.R.

Not to be confused with the Danish publicity stunt Dogma 95, this all-American publicity stunt, a comedy about Catholicism by New Jersey yahoo Kevin Smith (Clerks, Chasing Amy), can be recommended to 11-year-olds of all denominations. Older folks who want to kid themselves that they’re engaging important issues by provoking intolerant believers will undoubtedly get plenty of kicks too. But I couldn’t care less whether Smith’s metaphysical conceits about the war between Good and Evil are those of a devout believer or an atheist. The bottom line is that they’re puerile and that people repeatedly saying things like What the fuck is this shit? doesn’t make Smith either a satirist or a disciple of Preston Sturges. And his clodhopper handling of actors Linda Fiorentino, Alan Rickman, Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, Salma Hayek, and Jason Mewes — only Chris Rock comes out more or less unscathed — makes this 125-minute movie seem interminable. (JR) Read more

Leda

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1999). — J.R.

Claude Chabrol’s first color feature (1959), also known as À double tour and Web of Passion, adapts a Stanley Ellin thriller in which a bourgeois family’s oedipal conflicts lead to murder. The beautiful color cinematography of Aix-en-Provence is by Henri Decae, and the film is plotted with a mise en scène that suggests Alfred Hitchcock. The lively if uneven cast includes Jean-Paul Belmondo, the creepy André Jocelyn, Madeleine Robinson, Bernadette Lafont, and nouvelle vague axiom Laszlo Szabo. It’s not a total success, but it was one of the first pictures to translate the French New Wave’s genre interests into mainstream terms, and it’s full of sexy and irreverent (as well as brightly irrelevant) details. (JR)

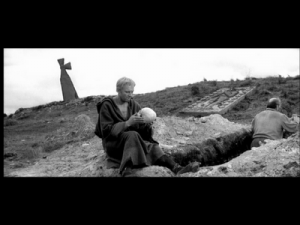

Hamlet

From the Chicago Reader (August 17, 2001). — J.R.

Critic Robin Wood recently cited this stunning 1964 Russian version of Shakespeare’s tragedy as the only one that “could be claimed as having the stature, as film, that the play has as theatre,” and it’s easy to see what he means. Shot in black-and-white ‘Scope, in dank interiors and seaside exteriors every bit as atmospheric as those in Orson Welles’s Othello, this runs 140 minutes but feels more stripped-down for brisk action than such vanity productions as Laurence Olivier’s and Kenneth Branagh’s, and consequently may be more compelling as narrative. Director Grigori Kozintsev (The New Babylon, The Youth of Maxim) adapted a translation by Boris Pasternak, and Dmitri Shostakovich contributed the score. Playing the title role, Innokenti Smoktunovsky isn’t as likable as some other Hamlets, but his struggles seem more evenly matched with those of the other characters. Facets Multimedia Center, 1517 W. Fullerton, Thursday, August 23, 6:30, 773-281-4114.

All The Vermeers In New York

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1992). This masterpiece about money, love,and art looks even better today, over three decades after it was made. Catch it now on MUBI before it leaves! — J.R.

Jon Jost’s ravishing independent feature about art, money, and loneliness in Manhattan — beautifully shot in ‘Scope by Jost himself and with a wonderful, Gil Evans-ish big-band jazz score by Jon A. English — can be viewed as a kind of companion piece to Jost’s earlier Rembrandt Laughing (1988), which dealt with several friends and acquaintances over several months in San Francisco. The main characters here are three young women who share a spacious apartment — Emmanuelle Chaulet (from Rohmer’s Boyfriends and Girlfriends), Katherine Bean, and Grace Phillips — and a Wall Street broker (Stephen Lack) who loves the Vermeers in the Metropolitan Museum. As in Jost’s other features, the narrative is elliptically constructed — the film seems more concerned with evoking a place, time, and milieu than with a dramatically shaped story — but there’s still a lot of lyrical passion and drama in the sounds, images, and characters themselves (1990). (JR)

Chicago

A bored festival report that I did for Cinemaya, Winter 1991-1992. -– J.R.

The Chicago International Film Festival is now 27 years old, making it one of the oldest film festivals in the U.S. because its founder, Michael Kutza, has remained its director, it might be said to have retained its overall focus — or, in fact ,the lack of focus — since the beginning, which might be described as an emphasis on quantity rather than a discernible critical position. (Having moved to Chicago in 1987, I’ve been present only for the last five festivals, but local critics who have been around much longer assure me that it hasn’t gone through any radical changes.)

To cite one instance of what I mean, it is the only festival that comes to mind that has consciously and deliberately programmed bad films on occasion for their camp appeal. Certain other titles often appear to be picked at random, and the festival has at times shown enough inattentiveness to various year-long non-commercial film venues in Chicago to reprogram certain films that have already been shown at the Art Institute’s Film Center or Facets Multimedia Center.

One hundred and twenty features were scheduled at the festival in 1991, and while a few of these never turned up, there were still many more films shown over 15 days in mid-October than the critics knew what to do with. Read more

Hoodlum Soldier

From the Chicago Reader. I’ve lost track of when this was published, but I know it wasn’t in October 1985, which is listed on the Reader’s web site — over two years before I joined the staff there. I would guess this probably appeared around fourteen years later. — J.R.

I’ve seen about a dozen of the 57 features directed by the fascinating and criminally neglected Yasuzo Masumura (1924-1986), and while no two are alike in style, many are socially subversive and most skirt the edges of exploitation filmmaking. This 1965 black-and-white ‘Scope comedy is also known as Yakuza Soldier; Shintaro Katsu, star of the popular Zatoichi films, plays an amiable, earthy yakuza thug drafted into Japan’s war with Manchuria prior to World War II, during which his main companion, the story’s narrator, is an intellectual with a similarly jaundiced view of military discipline. Made a year before the even more remarkable violent antiwar film Red Angel, this film features a lot of slapping and bone crunching, all of it administered by Japanese against other Japanese; significantly, the violence involving Manchurians is ignored. The irreverent ambience at times suggests Mister Roberts, with the pertinent difference that desertion is regarded as a sane and reasonable response to a soldier’s life. Read more

The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen

From the August 1, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Terry Gilliam’s third fantasy feature (1989) may not achieve all it reaches for, but it goes beyond Time Bandits and Brazil in its play with space and time, and as a children’s picture offers a fresh and exciting alternative to the Disney stranglehold on the market. The famous baron (John Neville) sets off with a little girl stowaway (Sarah Polley) on an epic journey to save a city in distress; among the other actors are Oliver Reed, Eric Idle, Jonathan Pryce, Valentina Cortese, and Robin Williams in a wonderful uncredited cameo as the Moon King. PG, 126 min. (JR)