A slightly different version of the Introduction to my 2004 collection, Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. — J.R.

Introduction

As the son and grandson of small-town exhibitors — a legacy explored in detail in my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980/1995) — I find it difficult to pinpoint with any exactitude when my film education started. But I can recall two pivotal early steps during my freshman year at New York University in 1961, when I was an English major still aspiring to become a professional novelist: taking the first and only film course I’ve ever had in my life and purchasing my first film magazine.

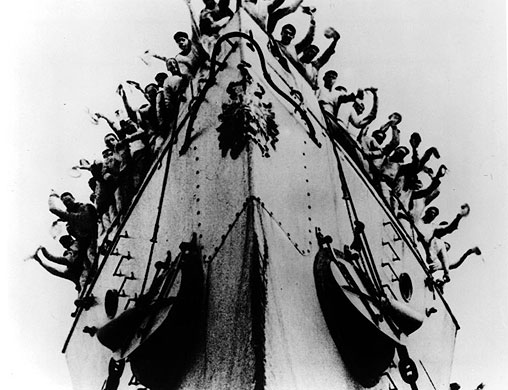

The course was an introductory survey taught by the late Haig Manoogian, who was serving as Martin Scorsese’s mentor in production courses around the same time. For me, it mainly afforded me my first opportunity to see The Birth of a Nation, The Last Laugh, and a few other film history staples; since I had no interest in making movies — or at this point in writing about them — I couldn’t work up much enthusiasm for such matters as “story values” that Manoogian tended to emphasize. Read more