As far as I know, this is the only surviving remnant, at least on paper, of a lecture I gave at what may have been the first international and academic conference devoted to Orson Welles, held at New York University in May 1988. The footnotes haven’t survived. — J.R.

Note: The following is a revised version of a paper which was initially structured around four lengthy excerpts from the Huckleberry Finn radio show presented on The Campbell Playhouse. In order to make this adaptation, I have eliminated all of my remarks about music and sound effects and given more emphasis to allusion and description rather than citation. Interested readers are urged to consult the radio show, available on Mark 56 Records (no. 634), P.O. Box One, Anaheim, CA 92805. [April 2015: This can now be accessed online and for free here.]

Huckleberry Finn was broadcast on The Campbell Playhouse on March 17, 1940, during the period when Orson Welles was commuting every week between Hollywood and New York. Herman Mankiewicz was working on the first draft of the Citizen Kane script at the time. Three and a half months had passed since the final version of the film script of Heart of Darkness had been completed, and two months since the final script of The Smiler with the Knife.

I haven’t been able to establish the authorship of the Huckleberry Finn script. [2015 note: It was in fact written by Herman G. Mankiewicz.] It seems to me highly likely that Welles had an important influence in shaping the script, whether or not he wrote it himself, but most of what I’ll have to say doesn’t hinge on a strictly auteurist argument. To cite an analogous situation, I don’t think it matters a great deal whether Jean-Luc Godard or Jean-Pierre Gorin scripted the various references to Godard’s earlier work which appear at the beginning of the film Tout va bien: either way, the film has just as much to say about the Godard persona. I don’t think there’s any doubt that Welles played a substantial role and creating and manipulating his own persona in the late 30s and early 40s, but it’s also clear that other contributing factors — such as the unexpected public response to The War of the Worlds — were out of his sphere of control . So please keep in mind that when I refer to Welles here, I’m mainly referring to the public persona, not to the private individual.

Welles begins the Huckleberry Finn show, before the first commercial break,. with Mark Twain’s own disclaimer: “Persons attempting to find a motive in this narratie will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot. BY ORDER OF THE AUTHOR.” Then, after the first commercial break, he adds a disclaimer of his own:

Last week, we said that this week we’d broadcast Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Well, you’re expecting, then, a dramatization — good, clear, concise. Ladies and gentlemen, you’ll hear no such thing. We’ re sorry, but we think Huckleberry Finn is too good a book to be dramatized, exactly speaking, and so we won’t. We won’t even try a nicely plotted version — we couldn’t do it anyway; we don’t even have to. For one thing, the story hasn’t even got what you’d call a nice plot.

The principle part of it, of course, relates to the deathless saga of a voyage down the Mississippi by the most celebrated raft the world has ever known. We ‘re going to tell most of that story, and as many of the others as we can, and as nearly as possible, and in Mark Twain’s own words.

Following this, we get, with the introduction of the show’s guest star, Jackie Cooper, Welles offering a kind of cartoon version of his public persona, with particular emphasis on jokes about his vanity and megalomania:

Now you’ll forgive me, please, but I must in inject what may seem at first to be the personal note. Ladies and gentlemen, it would appear that during the course of this past week, there have been circulated rumors — rumors evil, unfounded, and unfair, nasty, vile rumors whose sources I cannot place and whose origins I am at a loss to discover. It has been said that I will perform the role of Huckleberry Finn.

You’ll all be relieved, I’m sure, to hear from my own lips that this is not the case. It must be said, however, in all candor, that I restrain myself none too easily. To be Huckleberry Finn even for an hour — this was not likely to be put to one side. However, I’m as happy as possible and as proud as I really ought to be to welcome now to the Campbell Playhouse that gifted and very young performer who will be Huckleberry Finn — and who is actually Jackie Cooper. (Music begins.)

This is followed by an exchange which begins with Cooper saying, “I’m mighty proud to meet you, Mr. Welles,” already clearly assuming the part of Huck Finn, and Welles replying, “Huckleberry Finn, any friend of Mark Twain’s is always welcome here.”

To contextualize Welles’ public persona a bit, we should bear in mind that three years earlier, when Welles was presenting Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus and Blitzstein’ s The Cradle Will Rock at the age of twenty-one on the New York stage, he may have been a star of the theater, but he wasn’t yet a household word. In fact, he made a lot of his income during this period capitalizing on his anonymity in his freelance radio jobs, which helped him in impersonating various famous people on The March of Time. Then, in fairly swift succession, he appeared on the cover of Time, created a scandal with The War of the Worlds, and signed first a contract with Campbell Soup in 1938, then a contract with RKO in 1939. So while personal and autobiographical elements were already present in his work before this entry into the mainstream, fame meant that these elements were no longer subtexts of this work but part of its overt meaning.

The first Mercury radio series, First Person Singular, which broadcast eight programs in the summer of 1938, was basically built around the premise of Welles as first person narrator. As he was quoted saying in Newsweek (July 11 , 1938, the day of the show’s premiere) : “This method frees the script writer from the necessity of attempting to introduce a description of the locale into the dialogue….A radio audience is apt to be bored when it hears someone say, ‘Once upon a time.’ Not so if you say, ‘This happened to me. ‘”

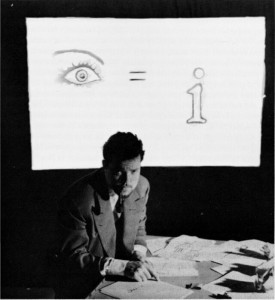

A year later, while Welles was working on Heart of Darkness as his first feature film project — after having adapted the ·Conrad novella on the air in a followup series to First Person Singular called Mercury Theater on the Air — this became a further exploration of the use of first person singular in film terms, through offscreen narration and subjective camera, with Welles playing both the offscreen Marlow and, eventually, the on-screen Kurtz. When I discussed this latter project with Welles fourteen years ago, he emphasized to me that his playing of Marlow was much more important to his conception than his playing of Kurtz — which is worth stressing, because the more contemporary view of Welles might place more importance on bis playing of Kurtz . In fact, Welles insisted to me that he only decided to play Kurtz after he gave up try ing to find another actor for the part. Although it’s very easy to see today how Welles’ fascination with Kurtz paralleled Chaplin’ s fascination with Hitler in The Great Dictator, which was being shot at the same time, it’s important to realize that his role as first person narrator –- and Welles ‘ projected handling of first person camera — already expresses a combined attraction and repulsion towards the figure of Kurtz.

In the beginning of Huckleberry Finn, we hear Welles being forced to abandon the first person, and then reappearing periodically to narrate portions of the story in the third person as himself, usually in the guise of a power play or tug of war between the show’s two main stars. (Welles : “Can’t I have just a paragraph or two, Huck?” And Cooper, much later: “That’s more than a paragraph or two, Mr. Welles .”) This brings about the forced coexistence of Huck Finn and Mr. Welles — a collapsing of two time frames and two orders of reality. It’s the kind of synthesis that theoretically sounds conceivable only on radio, although it’s worth noting that the implied coexistence of Orson Welles and the characters Don Quixote and Sancho Panza — the latter two dubbed by Welles himself, in Welles’ unfinished film of Don Quixote, suggests a certain parallel. It’s interesting to note, in any case, that being in charge of first-person narration in Huckleberry Finn seems associated with having an insider’s view. Jackie Cooper, as Huck, describes himself as if he were an acquaintance of Mark Twain’ s, while Welles as a character, by contrast, becomes a kind of voyeur who periodically usurps the role of Twain (storyteller) –- as well as that of Huck (subject and central focus), but who doesn’t share Mark Twain’s vantage point, as Huck does.

Obviously part of the issue here is age. Jackie Cooper was only eighteen when he did the show — at the same time that he was playing the lead in the Hollywood version of Booth Tarkington’s Seventeen, which must have made Welles even more envious –while Welles was almost twenty-five. As a onetime teenage runaway himself, one can easily see why Welles might want to appropriate Huck Finn as part of his own myth, even if the class difference between Huck and Welles is perhaps even more striking than the age difference. But, as mentioned earlier, Welles is offering a cartoon version of himself here, and one which was to persist in media for many years to come, as Welles the precocious brat.

As one indication of both the longevity of this image and Welles’ own complicity in perpetuating it, let me cite a parody of Welles which was presented on the Mercury Theater in 1946 by Fletcher Markle, a Canadian radio actor and director who later became a good friend of Welles. The show was called Life with Adam; it was originally produced and broadcast in Canada, but after hearing it, Welles decided to introduce it and present it in his own series, being quite explicit about the fact that its target was himself and his own affectations. It’s worth stressing that this impulse towards autocritique — which generally made Welles a much better and more persuasive critic of Welles than either Charles Higham or Pauline Kael (or Robert L. Carringer, for that matter) — is a constant in his career. It’s there in all of his feature s, and it’s every bit as pronounced in his script for The Cradle Will Rock, which he wrote in 1984, as it is in Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, The Lady from Shanghai, Touch of Evil, The Fountain of Youth, Falstaff, The Immortal Story, F for Fake, and Filming Othello, to cite only the most obvious examples.

For Mark Twain, the reason for a disclaimer at the beginning of his novel appears to be a cover-up for his own unwitting self-exposure: whether or not he was consciously aware of it, Huckleberry Finn certainly does have a motive, a moral, and a plot. Welles’ adaptation may incidentally have these things as well, but not with the same degree of purpose or focus, because the more episodic, humorous , and picaresque aspects of the novel — specifically the appearances of Tom Sawyer, the Duke, and the Dauphin, who are perhaps the novel ‘s three principle charlatans — are allowed to dominate. Jim is still present, of course, but not with the same degree of moral authority or centrality that he has in the original; he’s more often the occasion for comedy than for difficult moral decisions, such as Huck deciding to go to hell by sticking with a runaway slave. Some of this changed emphasis may simply reflect the racial ideology of white-controlled radio in 1940, in contrast to the implied radicalism of the novel. Despite Welles’ liberalism, particularly on the subject of race, we have to remember that black roles in the media in the early 1940s were rarely more progressive or extended than the parts played by servants in Val Lewton films.

The fact that charlatans rather than Jim hog so much of the spotlight may also have something to do with their relative theatricality. Like everyone else in the novel, they have a clear relation. to the freedom of the river, but their appreciation of that freedom proves to be mainly bogus. Huck and Jim basically lie in order to save their own skins; the Duke, the Dauphin, and Tom, who are already free, lie for their own amusement and profit, and wind up enslaving Huck in their own nefarious pursuits, although he seems only dimly aware of just how deferential be is to these despots.

With this overall shift of emphasis away from Jim as a moral influence, Welles is correct to preface his show with Twain’ s disclaimer as well as his own. While his show may have certain motives, morals, and plots, and contrary to his initial claim, does dramatize certain scenes from the novel, it doesn’t have a motive, a moral, and a plot in the sense that the original does, and consequently it can’t dramatize them. In terms of Welles ‘ persona, it reverts to the return of the repressed: Welles finally does get to pl2y in the story as an actor, not simply as a narrator, in the role of the Dauphin, which he plays opposite Walter Catlett as the Duke. In short, deprived of the hero’s role, he turns up as _ the devil’s advocate. In his introduction to the show, Welles introduces Catlett after Cooper as a late addition to the program, and identifies him as the voice of J. Worthington Foulfellow the Fox in the current Walt Disney release, Pinocchio — not a dissimilar role, as it turns out.

More prosaically, it is clear that the attraction of playing the Dauphin for Welles is the opportunity of playing a Shakespearian ham. This gives his character several autobiographical reference points: not only his own fairly recent stage productions of Shakespeare — Macbeth in 1936, Julius Caesar in 1937, and Five Kings in 1938 — but also, perhaps closer to the mark, his more recent encounter ,with old-time Victorian vaudeville and 19th century melodrama, which included his impersonations of John Barrymore, Alfred Lunt, and Charles Laughton; in his production of William Archer’ s The Green Goddess, which he performed in Chicago on the RKO vaudeville circuit, en route to Hollywood in 1939. (Incidentally, at my one meeting with Welles in 1972, I recall him mentioning that he grew a beard for The Green Goddess which he still had when he got to Hollywood.)

The playful struggle for power over who gets to narrate Huckleberry Finn foregrounds a number of narrative and theatrical conventions: the substitution of narrative time for real time, the pretenses involved in acting, and the narrative-illusionist line of propriety which traditionally separates an internal character from an external narrator. At the very end of the program, after the story comes to an end, Welles briefly draws attention to the fact that he played the Dauphin — just in case any listeners didn’t recognize him — by momentarily assuming the character’s intonations, which reiterates the degree to which, for better and for worse, the story of Huck Finn’s desire has become the story of Orson Welles’ desire. But being honest and self-critical about this, the story’s conclusion also acknowledges that there’s something troubling and troubled about the adaptation, something unsettled even about whether the ending is a happy one or not:

Welles : A happy ending, eh, Huck?

Cooper: Well, that depends on what you call happy, Mr. Welles.

Welles: Well I should say you all ought to be happy.

Cooper: Well, that’s just it. You should say. It just so happens that I’m Huckleberry Finn, and Mr. Twain wrote the book about me, and I’m the one to say.

Welles: Hmmm. All right, Huck. You say.

This looks ahead towards the ambiguous finale of Welles’ 1982 screenplay The Big Brass Ring, which has plenty of Tom Sawyerish aspects of its own, and which concludes, parenthetically, “If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story.” In the concluding portions of the story, there is an almost audible sigh of relief when Tom Sawyer turns up to take over the plot, not long after the Duke and the Dauphin have been dispensed with. Like Elmyr de Rory and Clifford Irving in F for Fake, these characters represent an impulse which counters the impulse towards autocritique in Welles — namely, the desire to disappear like a magician in a puff of smoke, to hide and lose one’s self rather than expose one’s self in the work.

The question of who has the narrative voice in Huckleberry Finn is never fully resolved, so until Jackie Cooper finally abandons Huck, after the last commercial break, the narrative can only hurry to a close in the form of a petulant argument. And even after the narrative is officially over, the baring of the device continues in Welles ‘ voice revealing himself as the Dauphin, in order to reiterate that the auto biographical subtext still takes precedence — an insistence that is maintained throughout the show by means of what J. Hoberman has called “vulgar modernism, ” and which might also be called modernism with its gloves off.

If Welles had been a few years younger and had been able to play Huck Finn, is it reasonable to expect that the moral tenor of the original might have been respected more closely? For isn’t the principle of every adaptation in the Wellesian oeuvre a matter of converting every work into a personal confrontation, a moral self-reckoning, so that we, as audience, might treat it the same way ourselves?