From the Chicago Reader (October 10, 2003). — J.R.

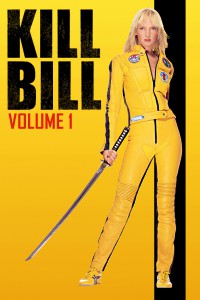

Quentin Tarantino’s lively and show-offy 2003 tribute to the Asian martial-arts flicks, bloody anime, and spaghetti westerns he soaked up as a teenager is even more gory and adolescent than its models, which explains both the fun and the unpleasantness of this globe-trotting romp. It’s split into two parts, and I assume the idea of volumes reflects the mind-set of a former video-store clerk who thinks in terms of shelf life. This is essentially 111 minutes of mayhem, with hyperbolic revenge plots and phallic Amazonian women behaving like nine-year-old boys; the dialogue, less spiky than usual, uses bitch as often as his earlier films used nigger, and most of the stereotypes are now Asian rather than black. If Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog was a response of sorts to Tarantino, then Tarantino returns the compliment here with RZA’s music and the mixture of Japanese and Italian genre elements. With Uma Thurman, Lucy Liu, Sonny Chiba, Daryl Hannah, Julie Dreyfuss, and Chiaki Kuriyama. R. (JR)