From the Winter 1972–1973 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

REPORTER: Who are your favorite characters in the movie?

BUÑUEL: The cockroaches.

— from an interview in Newsweek

“Once upon a time . . .” begins UN CHIEN ANDALOU, in mockery of a narrative form that it seeks to obliterate, and from this title onward, Buñuel’s cinema largely comprises a search for an alternative form to contain his passions. After dispensing with plot entirely in UN CHIEN ANDALOU, L’AGE D’OR, and LAS HURDES, his first three films, and remaining inactive as a director for the next fifteen years (1932–1947), Buñuel has been wrestling ever since with the problem of reconciling his surrealistic and anarchistic reflexes to the logic of story lines. How does a sworn enemy of the bourgeoisie keep his identity while devoting himself to bourgeois forms in a bourgeois industry? Either by subverting these forms or by trying to adjust them to his own purposes; and much of the tension in Buñuel’s work has come from the play between these two possibilities.

Buñuel can always tell a tale when he wants to, but the better part of his brilliance lies elsewhere. One never finds in his work that grace and economy of narration, that sheer pleasure in exposition, which informs the opening sequences of GREED, LA RÈGLE DU JEU, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, REAR WINDOW, SANSHO DAYU, and AU HASARD, BALTHAZAR. On the contrary, Buñuel’s usual impulse is to interrupt a narrative line whenever he can find an adequate excuse for doing so — a joke, ironic detail, or startling juxtaposition that deflects the plot’s energies in another direction. A typical “Buñuel touch” — the “Last Supper” pose assumed by the beggars in VIRIDIANA — has only a parenthetical relation to the action, however significant it may be thematically. And lengthier intrusions, like the dream sequence in LOS OLVIDADOS, tend to detach themselves from their surroundings as independent interludes, anecdotes, or parables. For the greater part of his career, Buñuel’s genius has mainly expressed itself in marginal notations and insertions. To my knowledge, his only previous attempt at an open narrative structure since 1932 has been LA VOIE LACTÉE — a picaresque religious (and antireligious) pageant, much indebted to Godard’s WEEKEND, which came uncomfortably close to being all notations and no text, like a string of Sunday school jokes.

If LE CHARME DISCRET DE LA BOURGEOISIE registers as the funniest Buñuel film since L’AGE D’OR, probably the most relaxed and controlled film he has ever made, and arguably the first contemporary, global masterpiece to have come from France in the 70s, this is chiefly because he has arrived at a form that covers his full range, permits him to say anything — a form that literally and figuratively lets him get away with murder. One cannot exactly call his new work a bolt from the blue. But its remarkable achievement is to weld together an assortment of his favorite themes, images, and parlor tricks into a discourse that is essentially new. Luring us into the deceptive charms of narrative as well as those of his characters, he undermines the stability of both attractions by turning interruption into the basis of his art, keeping us aloft on the sheer exuberance of his amusement.

Seven years ago, Noël Burch observed that in LE JOURNAL D’UNE FEMME DE CHAMBRE, Buñuel had at last discovered Form — a taste and talent for plastic composition and a “musical” sense of the durations of shots and the “articulations between sequences”; more generally, “a rigorous compartmentalisation of the sequences, each of which follows its own carefully worked out, autonomous curve.”[*] BELLE DE JOUR reconfirmed this discovery, but LE CHARME DISCRET announces still another step forward: at the age of seventy-two, Buñuel has finally achieved Style.

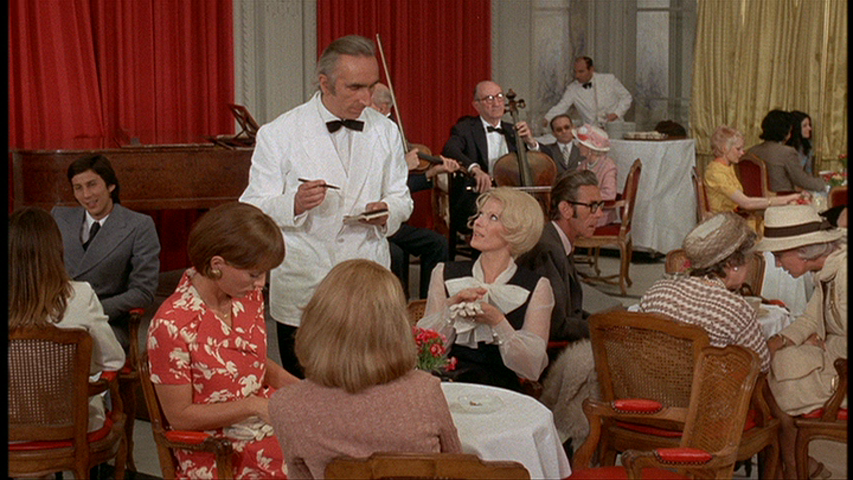

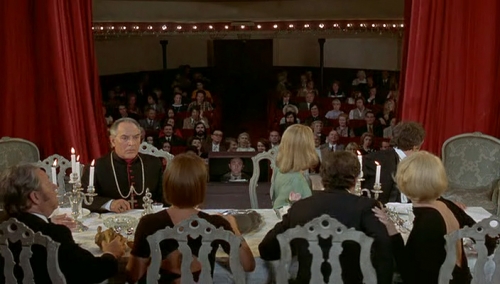

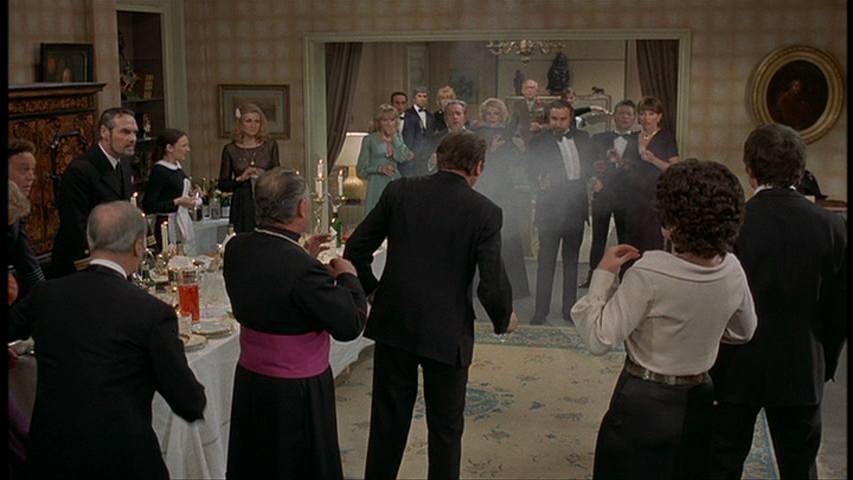

Six friends — three men and three women — want to have a meal together, but something keeps going wrong. Four of them arrive at the Sénéchals’ country house for dinner, and are told by Mme Sénéchal that they’ve come a day early; repairing to a local restaurant, they discover that the manager has just died, his corpse laid out in an adjoining room — how can they eat there? — so they plan a future lunch date. But each successive engagement is torpedoed: either M. and Mme Sénéchal (Jean-Pierre Cassel and Stéphane Audran) are too busy making love to greet their guests, or the cavalry suddenly shows up at dinnertime between maneuvers, or the police raid the premises and arrest everyone. Don Raphael Acosta (Fernando Rey), Ambassador of Miranda — a mythical, campy South American republic resembling several countries, particularly Spain — arranges a secret rendezvous in his flat with Mme Thévenot (Delphine Seyrig), but M. Thévenot (Paul Frankeur) turns up at an inopportune moment. The three ladies — Mmes Sénéchal and Thévenot and the latter’s younger sister, Florence (Bulle Ogier) — meet for tea, and the waiter regretfully announces that the kitchen is out of tea, coffee, alcohol, and everything else they try to order. Still other attempted get-togethers and disasters turn out to be dreams, or dreams of dreams. At one dinner party, the guests find themselves sitting on a stage before a restive audience, prompted with lines; another ends with Don Raphael, after a political quarrel, shooting his host; still another concludes with an unidentified group of men breaking in and machine-gunning the lot of them.

At three separate points in the film, including the final sequence, we see all six characters walking wordlessly down a road, somewhere between an unstated starting place and an equally mysterious destination — an image suggesting the continuation both of their class and of the picaresque narrative tradition that propels them forward. Yet if the previous paragraph reads like a plot summary, it is deceptive. The nature and extent of Buñuel’s interruptions guarantee the virtual absence of continuous plot. But we remain transfixed as though we were watching one: the sustained charm and glamour of the six characters fool us, much as they fool themselves.

Their myths, behavior, and appearance — a seductive, illusory surface — carry us (and them) through the film with a sense of unbroken continuity and logic, a consistency that the rest of the universe and nature itself seem to rail against helplessly. Despite every attempt at annihilation, the myths of the bourgeoisie and of conventional narrative survive and prevail, a certainty that Buñuel reconciles himself to by regarding it as the funniest thing in the world.

Interruptions, of course, are a central fact about modern life; as I write this in a friend’s apartment, the phone has been ringing about once every two paragraphs. Using this sort of comic annoyance as a structural tool, Buñuel can shoot as many arrows as he wants into our complacencies about narrative, the characters’ complacencies about themselves. He exercises this principle of disruption in a multitude of ways, in matters large and small: in the opening scene at the Sénéchals’ house, Florence’s dopey, indifferent, comic-strip face drifts irrelevantly into the foreground of a shot while other characters chatter about something else behind her, and similar displacements of emphasis abound everywhere.

Take the last attempted dinner. It begins with a red herring that leads us to suspect poisoning (“I prepared the soup with herbs from the garden”); the conversation is broken off for a cruel exchange with the maid about her age and broken engagement; and while M. Sénéchal demonstrates the correct method of carving lamb, Florence stubbornly insists on pursing her deadpan astrological profile of Don Raphael. After the gang breaks in to shoot them all, our sense of their total demise — a Godardian image of overlapping corpses — is interrupted when we realize that Don Raphael has hidden under the dinner table, and is reaching for a piece of lamb. Still crouching under the table, he bites savagely into the meat — a comic-terrifying reminder of the dream in LOS OLVIDADOS — and is finished off by a final blast of gunfire. Lest we suppose that this is the last possible interruption, we next see Don Raphael waking up from his nightmare. He gets out of bed, goes into the kitchen, and opens the refrigerator to take out a plate of veal.

Every dream and interpolated story in the film carries some threat, knowledge, or certainty of death — the central fact that all six characters ignore, and their charm and elegance seek to camouflage. Ghosts of murder victims and other phantoms of guilt parade through these inserted tales, but the discreet style of the bourgeoisie, boxing them in dreams and dinner anecdotes, holds them forever in check. To some extent, Buñuel shares this discretion in his failure to allude to his native Spain even once in the dialogue, although the pomp and brutality of the Franco regime are frequently evoked. (The recurrent gag of a siren, jet plane, or another disturbance covering up a political declaration — a device familiar from Godard’s MADE IN USA — acknowledges this sort of suppression.) But the secret of Buñuel’s achieved style is balance, and for that he must lean more on irony — an expedient tactic of the bourgeoisie — than on the aggressions of the rebel classes; when he sought imbalance in L’AGE D’OR, the revolutionary forces had the upper edge. An essential part of his method is to pitch the dialogue and acting somewhere between naturalism and parody, so that no gag is merely a gag, and each commonplace line or gesture becomes a potential gag. Absurdity and elegance, charm and hypocrisy become indistinguishably fused.

Another form of resolution is hinted at in the treatment of a secondary character, Monsignor Dufour (Julien Bertheau), a bishop who is hired by the Sénéchals as a gardener (“You’ve heard of worker-priests? There are worker-bishops too!”), and figures as clergy-in- residence at many of the abortive dinner parties. Late in the film, he is brought to the bed of an impoverished dying man — a gardener himself — by an old woman who asserts that she’s hated Jesus Christ since she was a little girl, and promises to tell him why when she returns from delivering carrots. Dufour then proceeds to attend to the dying gardener, who confesses to having poisoned the bishop’s wealthy parents when Dufour was a child. Dufour kindly and dutifully gives him absolution, then lifts up a nearby rifle and shoots the man through the skull.

Thus Buñuel appears to arrive at the conclusion that Catholicism, far from being the natural opponent of Surrealism, is the ultimate expression of it; and it seems strangely appropriate that after this scene both the bishop and the old woman with her promised explanation are abruptly dropped from the film, as though they’ve suddenly canceled each other out.

Writing in 1962, Andrew Sarris remarked that Buñuel’s “camera has always viewed his characters from a middle distance, too close for cosmic groupings and too far away for self-identification.” The singular achievement of Buñuel’s crystallized style is to allow both these viewpoints to function — to let us keep our distance from the characters while repeatedly recognizing our own behavior in them. Cryptic throwaway lines, illogically repeated motifs, and displacements in space and time give the film some of the abstractness of MARIENBAD, yet the richness of concretely observed social behavior is often comparable to that in LA RÈGLE DU JEU. A similar mixture was potentially at work in THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL — the obvious companion film to LE CHARME DISCRET, with its guests unable to leave a room after finishing dinner. But despite a brilliant script, the uneven execution left too much of the conception unrealized.

Undoubtedly a great deal of credit for the dialogue of LE CHARME DISCRET should go to Jean-Claude Carrière, who has worked on the scripts of all Buñuel’s French films since LE JOURNAL D’UNE FEMME DE CHAMBRE: the precise banality of the small talk has a withering accuracy. Even more impressive is the way that Buñuel and Carrière have managed to weave in enough contemporary phenomena to make the film as up-to-date — and as surrealistic, in its crazy-quilt juxtapositions — as the latest global newspaper: Vietnam, Mao, women’s lib, various forms of political corruption, and international drug trafficking are all touched upon in witty and apt allusions.

Fernando Rey unloading smuggled heroin from his diplomatic pouch is a hip reference to THE FRENCH CONNECTION, and much of the rest of the film works as a parody of icons and stances in modern cinema. Florence’s neuroticism — as evidenced by her loathing of cellos and her “Euclid complex”— lampoons Ogier’s role in L’AMOUR FOU; Audran’s stiff elegance and country house hark back to LA FEMME INFIDÈLE; while Seyrig’s frozen, irrelevant smiles on every occasion are a comic variation of her ambiguous MARIENBAD expressions. And as I’ve already suggested, Godard has become a crucial reference point in late Buñuel — not only in the parodies and allusions but also in the use of an open form to accommodate these and other intrusions, the tendency to keep shifting the center of attention.

A few years ago, Godard remarked of BELLE DE JOUR that Buñuel seemed to be playing the cinema the way Bach played the organ. The happy news of LE CHARME DISCRET is that while most of the serious French cinema at present — Godard included — seems to be hard at work performing painful duties, the Old Master is still playing — effortlessly, freely, without fluffing a note.

— Sight and Sound, Winter 1972–1973

[*] “Two Cinemas,” Moviegoer, 3 (Summer 1966).