From the Chicago Reader (April 15, 1988).Reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995). — J.R.

MÉLO

****

Directed by Alain Resnais

Written by Henry Bernstein

With André Dussollier, Sabine Azema, Pierre Arditi,

and Fanny Ardant

The exquisite art of MÉLO, like the art of Alain Resnais in general, bears a certain resemblance to sculpture: it needs to be seen from several different vantage points if one is to fully appreciate its shapeliness and the powerful multiplicity of its meanings. The following selection of vantage points can’t pretend to be exhaustive; at best, it presents only a few starting points for sounding the bottomless depths of this deceptively simple movie. The first six points are provided by the film’s title and the names listed in the heading above. The last four — theater, mise en scène, symmetry, and mystery — offer more general and abstract perspectives.

1. MÉLO.

The title is an abbreviation for mélodrame or melodrama, which derive from the Greek word melos, music, and the French word drame, drama. What do we usually mean by melodrama? “Sensational dramatic piece with violent appeals to emotions” and “extravagantly theatrical play in which action and plot predominate over characterization” are two relevant dictionary definitions, among others. Read more

Commissioned by Arrow Films for their dual format boxed set, Jia Zhangke: Three Films, released in the U.K. in early 2018, and reprinted in my collection Cinematic Encounters: Portraits and Polemics (2019). — J.R.

It’s important to acknowledge that part of what makes Jia Zhangke the most exciting and important mainland Chinese filmmaker currently active also makes him one of the most disconcerting and sometimes even bewildering. This has a lot to do with his propensity for viewing fiction and non-fiction, and, even more radically, fantasy and reality, as reverse sides of the same coin, and, in keeping with this complex duality, a talent for bold stylistic shifts not only between successive films but between and within separate sequences. His ambitions are such that even his ‘failures’ are worth more than the successes of many of his colleagues — and, for that matter, what we might describe as a Jia ‘failure’ often means simply a film that we should see again and reconsider.

Confounding us still further in A Touch of Sin (2013), his seventh feature, Jia reverses his previous position of avoiding on-screen violence by delivering it this time by the bucketful. In his earlier features, treatments of violence tended to be reticent or elliptical, so that government executions in Platform (2000) registered as distant gunshots and the tragic and fatal industrial accident of a construction worker in The World wasn’t shown at all. Read more

This appeared in the March 20, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Michael Paxton

Narrated by Sharon Gless.

Primary Colors

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Mike Nichols

Written by Elaine May

With John Travolta, Emma Thompson, Adrian Lester, Kathy Bates, Billy Bob Thornton, Larry Hagman, and Maura Tierney.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Two highly partisan political movies are opening this week, a right-wing independent documentary and a left-wing Hollywood feature — though it’s not clear that the filmmakers of either would categorize their work in this way. Certainly it wouldn’t be any exaggeration to call both films the efforts of special interest groups — a movie about Bill Clinton put together by people who mainly qualify as his supporters and friends and a sincere hagiography of novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand fashioned by many of her disciples and acolytes. How far they actually carry their respective loyalties is a different matter, however. Ultimately both movies flounder as well as triumph because of their insider points of view, though not always for the same reasons.

Whenever Ayn Rand’s name comes up, I have an impulse to scoff, an impulse I think is shared by many others. Read more

I just heard the very upsetting news that the great Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi (The White Balloon, The Circle, Crimson Gold, Offside) was deprived today of his passport in Tehran, now making it impossible for him to leave Iran — reminding me, alas, of what happened to Pere Portabella in Franco Spain roughly half a century ago.

The two following short essays were commissioned by the Jeonju international Film Festival in February and March, 2009 and published in a bilingual catalog to accompany a Portabella retrospective held there in May.

It’s hard to keep up with all of Portabella’s activities these days, but his wonderful web site — which one can access in English, and which grows periodically in leaps and bounds — makes it somewhat easier to try. My most recent visit reveals that it’s now apparently possible to download several of his films on the Internet, directly from this site. I’m still eagerly anticipating the DVD box set that’s still apparently in the works, for which I wrote a commissioned essay (to be printed or reprinted in my next collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition: see Publications and Events on this site), but meanwhile here are a couple of commentaries about two of his early films — one of which, Cuadecuc, Vampir, remains my favorite of his works to date. Read more

Not so much a fantasy as a fantasia, Alain Resnais’ first novel adaptation, his second adaptation (after Mélo) and, unless my memory fails me, his fifth film in CinemaScope (after Le chant du styrène, Last Year at Marienbad, L’amour à mort, and Private Fears in Public Places), this brittle comedy may also be the most purely surrealist of all his films, especially in its emphasis on irrational impulses (as well as its non-sequitur final shot). And the fact that it’s often creepy (as well as very personal) is surely more of a plus than a minus; it hasn’t been acknowledged nearly enough that Resnais’ best and most beautiful films — including Statues Also Die, Toute la mémoire du monde, Le chant du styrène, Night and Fog, Hiroshima mon amour, Marienbad, Muriel, Providence, Mon oncle d’Amérique, Mélo, and Not on the Lips, among others — usually turn out to be his creepiest. (An exception to this rule is L’amour à mort, which is exceptionally creepy but also far from Resnais’ best.)

Seen twice on Friday at the New York Film Festival — first at a press screening, then at the $40 opening — this is a film whose pastel hues and intricate color coding (e.g., Read more

One of my best known reviews, from the July 24, 1998 Chicago Reader. For those who’d prefer to read a shorter version of the same argument, I’ll start with my capsule reviews of the two films. — J.R.

Small Soldiers

Director Joe Dante (Gremlins, Innerspace, Explorers, Matinee) is a national treasure, and his lack of recognition by the general public may actually make it easier for him to function subversively. His unpretentious fantasy romps have more to say about the American psyche, pop culture, and the ideology of violence than anything dreamed up by Steven Spielberg or George Lucas. This delightful adventure about war toys running amok in suburban middle America is a synthesis and extension of most of his previous movies, with echoes of Gulliver’s Travels (including some of the satire). The toys in question are the villainous Commando Elite, fashioned using a microchip from the U.S. Defense Department to mercilessly slaughter the noble if freakish Gorgonites, a set of toys programmed (like other minorities one can mention) to hide and to lose; the Ohio citizens who wind up in the cross fire are strictly generic sitcom types, but we wind up caring about them almost as much as we care about the toys. Read more

Missing from this review from the July 1975 Monthly Film Bulletin is any acknowledgment that Godard and Gorin’s rather punitive analysis against Jane Fonda’s role in a still photograph might have incidentally reflected some misogyny along with their resentment against the power of a movie star. For those interested in tracking down Letter to Jane, it’s included as an extra on the Criterion DVD of Tout va bien. —J.R.

Letter to Jane

France, 1972 Directors: Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Gorin

Letter to Jane was initially made to be shown in a specific limited context: as a short accompanying Tout va bien at the New York and San Francisco Film Festivals in 1972. As with all of Godard and Gorin’s joint projects, the essential aims of the film are demystification and political analysis. More generally, it pursues a demystification of cinema itself as art object, reflected in the minimal technical means used in the articulation of the filmmakers’ argument (a montage of stills separated by cuts or makeshift wipes accompanied by the voices of Godard and Gorin in English, with brief uses of recorded music as punctuation) — an approach further developed by Godard’s more recent work with video, which seeks to demonstrate that the “production of sounds and images” need not be as expensive or as technically elaborate as is usually supposed. Read more

These are expanded Chicago Reader capsules written for a 2003 collection edited by Steven Jay Schneider. I contributed 72 of these in all; here are the third dozen, in alphabetical order. — J.R.

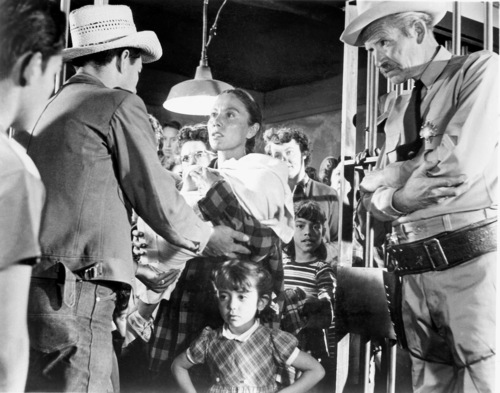

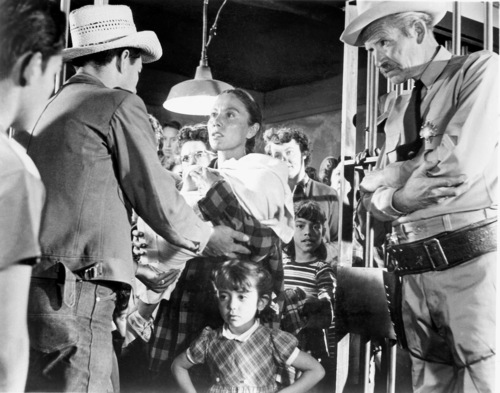

Salt of the Earth

This rarely screened 1954 classic is the only major American independent feature made by communists; a fictional story about the Mexican-American zinc miners in New Mexico then striking against their Anglo management, it was informed by feminist attitudes that are quite uncharacteristic of the period. The film was inspired by the blacklisting of director Herbert Biberman, screenwriter Michael Wilson (A Place in the Sun), producer and former screenwriter Paul Jarrico, and composer Sol Kaplan, among others; as Jarrico later reasoned, since they’d been drummed out of Hollywood for being subversives, they’d commit a “crime to fit the punishment” by making a subversive film. The results are leftist propaganda of a very high order, powerful and intelligent even when the film registers in spots as naive or dated. Basically kept out of American theaters until 1965, it was widely shown and honored in Europe, but it’s never received the recognition it deserves stateside. Regrettably, its best-known critical discussion in the U.S. is in Pauline Kael’s final essay in her first collection — a 1954 broadside in which this film is ridiculed as “propaganda” alongside a forgettable cold war thriller, Night People, that’s skewered as “advertising”. Read more

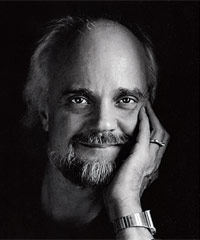

Born July 24, 1944, San Mareno, California. Died May 23, 2013, Chicago, Illinois.

Here’s something I said at a special tribute to Peter held in his presence at Columbia College, on October 4, 2012:

“For me, Peter Thompson is one of those special filmmakers who reinvents cinema for his own purposes, a trait that he shares not only with people like Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer, and Jacques Tati, but also with filmmakers like Chaplin, Welles, and Kubrick.

“On some level, all of Peter’s films are mysteries and detective stories, but ones in which Peter is inviting us to join him in becoming the detectives, not in giving us puzzles that he knows how to solve but in inventing new ways for us to share in his curiosity. You might even say that part of the mysteries of his films is determining what they’re about, because in addition to reinventing cinema they might be said to reinvent things like subject matter and research as well as still more difficult-to-define entities such as poetry and history and truth.

“Peter has been a friend for about two decades, but I hasten to add that we became friends because of my enthusiasm for his early work, which existed before we ever met. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 27, 1993). — J.R.

MANHATTAN MURDER MYSTERY

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Woody Allen

Written by Allen and Marshall Brickman

With Allen, Diane Keaton, Alan Alda, Anjelica Huston, Jerry Adler, Joy Behar, Ron Rifkin, and Lynn Cohen.

It’s instructive to divvy up Woody Allen’s movies into “art films” and entertainments. Without too much boiling and scraping, I think you could say that the entertainments come from his first 11 years as a filmmaker, from What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (1966, now missing from the press-kit filmography) to Annie Hall (1977), while his art-film efforts extend from Interiors (1978) to Husbands and Wives (1992).

Some would argue that Broadway Danny Rose (1984) and The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), coming halfway through the second period, belong to the entertainment category, along with “Oedipus Wrecks” (1989), his contribution to New York Stories, but I would beg to differ. (The first of these is in black and white, the second traffics in misery and pathos, and the third derives directly from Fellini’s episode in Boccaccio ’70 — the first pieces of counterevidence I’d cite.) Similarly, to those who’d claim that the “foreign movie” sketch in Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask) (1972) pushes it into the art-movie category, I’d maintain that there’s a world of difference between this film’s parody of Antonioni and the pastiches of the later movies. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 13, 2001). — J.R.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Written by Spielberg and Ian Watson

With Haley Joel Osment, Jude Law, Frances O’Connor, Brendan Gleeson, William Hurt, Jake Thomas, and the voices of Jack Angel, Ben Kingsley, Meryl Streep, Robin Williams, and Chris Rock.

If the best movies are often those that change the rules, Steven Spielberg’s sincere, cockeyed, serious, and sometimes masterful realization of Stanley Kubrick’s ambitious late project deserves to be a contender. All of Kubrick’s best films fall into one vexing category — they’re strange, semi-identified objects that we’re never quite prepared for. They’re also the precise opposite of Spielberg’s films, which ooze cozy familiarity before we’ve figured out what they are or what they’re doing to us. If A.I. Artificial Intelligence — a film whose split personality is apparent even in its two-part title — is as much a Kubrick movie as a Spielberg one, this is in large part because it defamiliarizes Spielberg, makes him strange. Yet it also defamiliarizes Kubrick, with equally ambiguous results — making his unfamiliarity familiar. Both filmmakers should be credited for the results — Kubrick for proposing that Spielberg direct the project and Spielberg for doing his utmost to respect Kubrick’s intentions while making it a profoundly personal work. Read more

Commissioned and published by New York’s Metrograph Chronicle in mid-December 2019. — J.R.

“Would you forgive me if I die?” — Question asked in the first scene of Heaven Knows What

The movies of Josh and Benny Safdie are dominated by compulsively impulsive hustlers who continuously revise their own lives as well as those of everyone else in their immediate vicinities, most often with chaotically disastrous consequences for everyone concerned. Maybe because these scheming and prevaricating characters know how to tell lies and (somewhat less often) how to apologize for or cover up their various messes, they also qualify, at least some of the time, as skillful escape artists as well as stylish con men. They exasperate their colleagues, spouses, and other family members, who almost invariably wind up forgiving these crumb-bums for their lies and deceptions after hearing their shame-faced apologies, which are typically followed by further deceptions. This dizzying pattern seems to culminate in their new film Uncut Gems, which registers at times as a slapstick remake of Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant (1992) — at least if one can allow for a substitution of a certain amount of manic Jewish optimism for depressive Catholic despair. Read more

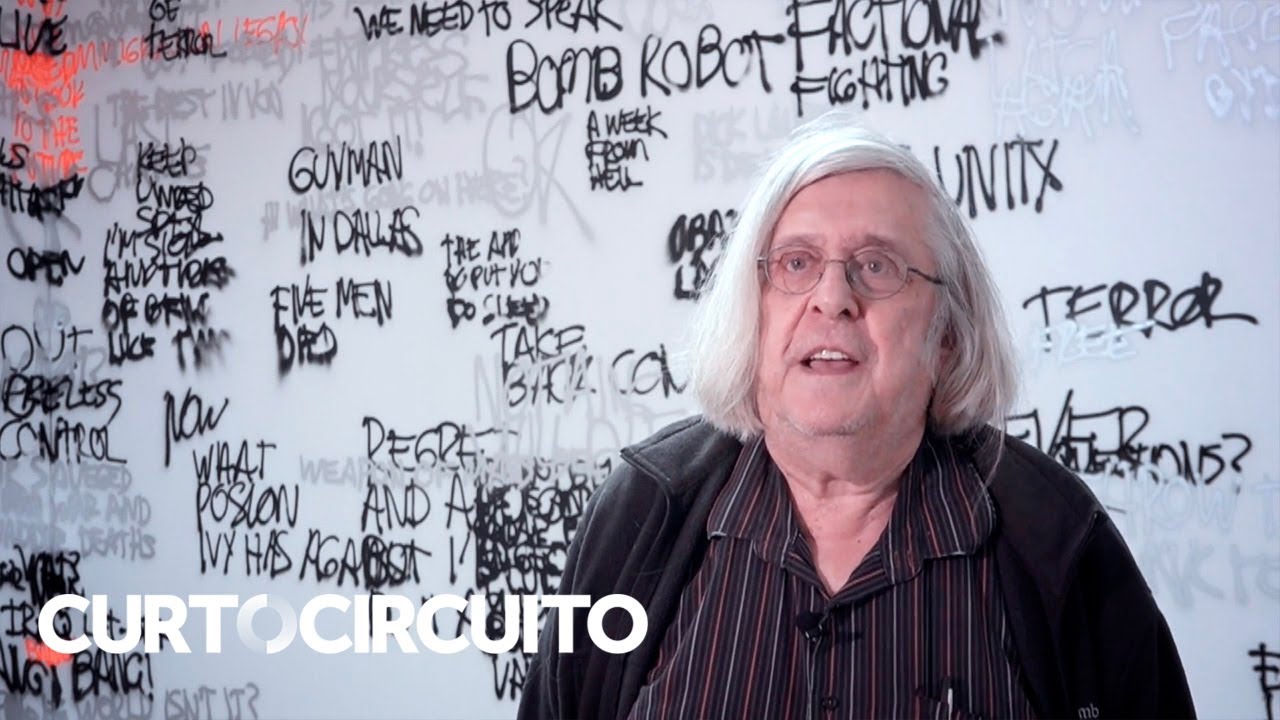

The following interview by Sara Donoso, printed in Spanish and English in Fotocinema no. 14 (2017), was conducted in Santiago de Compostela while I was serving on the jury of Curtocircuíto, the international festival of short films held there. I’ve taken the liberty of lightly revising Donoso’s English, and I’ve also retained her Spanish introduction.– J.R.

THE EXPANSION OF CRITICISM: AN INTERVIEW WITH JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

Sara Donoso

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, España

saradonosocalvo@gmail.com

Crítico, ensayista y teórico de cine, la pluma de Jonathan Rosenbaum es de aquellas que practican el ejercicio de la resistencia; que se oponen a la clasificación, las etiquetas, al mundo del mainstream y a la cultura del espectáculo. Podríamos decir que es uno de esos críticos tal vez incómodos para algunos pero necesarios y reveladores para quienes aprecian el séptimo arte. Tras trabajar como principal crítico del Chicago Reader entre 1987 y 2008, actualmente sigue ejerciendo el ejercicio de la escritura cinematográfica a través de su página web, en la que no solo postea periódicamente reseñas de libros o películas sino que cuenta además con un archivo de publicaciones anteriores.

Como autor y editor, ha contribuido a través de diferentes proyectos a la difusión y dignificación del cine más allá de los circuitos comerciales, siendo responsable de títulos como Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (2003),Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) o Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (2010). Read more

This appeared in the August 21, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

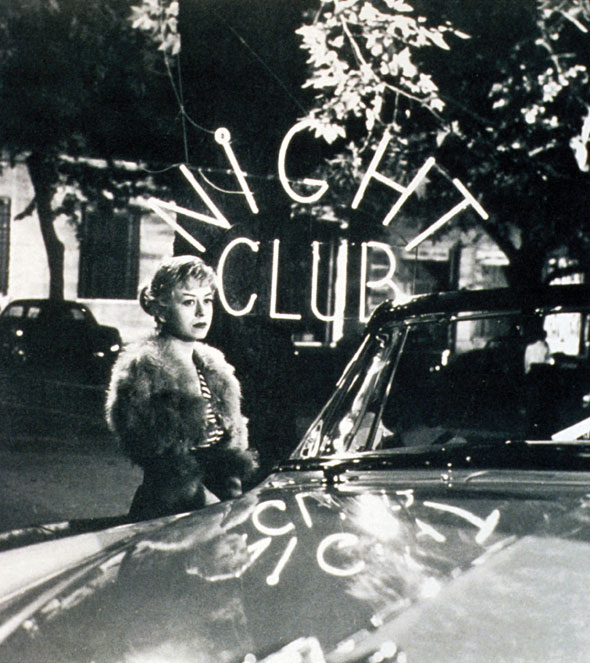

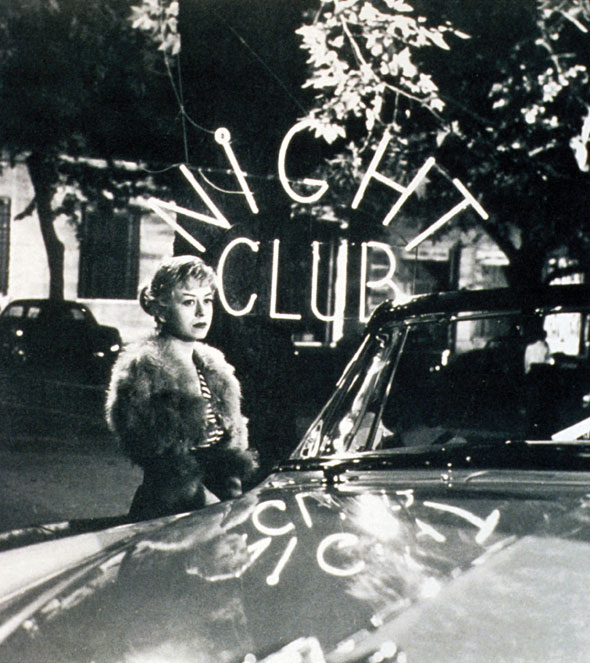

Nights of Cabiria

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Federico Fellini

Written by Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, and Pier Paolo Pasolini

With Giulietta Masina, Franca Marzi, Francois Perier, Amedeo Nazzari, Dorian Gray, and Aldo Silvana.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Reporting on the response to Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria at Cannes in 1957, François Truffaut wrote, “Let us deplore the fad that seems to be shared equally by the audience, producers, distributors, technicians, actors, and critics who fancy that they can contribute to the ‘creation’ of the films being shown by deciding how they should have been edited and cut. After each showing, I’d hear things like ‘Not bad, but they could have cut a half-hour,’ or ‘I could have saved that film with a pair of scissors.'” As festival responses to more recent masterpieces like Taste of Cherry and The Apostle have shown, this fad is still very much with us. Another, more recent fad is to release longer versions of films that were butchered on their release. Too often these so-called director’s cuts — such as Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and the forthcoming Touch of Evil — can’t qualify as restorations, however, because the directors were never accorded final cut in the first place. Read more

This may be Antonioni’s most unjustly neglected fiction feature, at least in the U.S. (though even in France, where it’s on DVD, it’s only available in a box set). I reviewed it for the May 1975 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin. –J.R.

Signora Senza Camelie, La

(The Lady Without Camelias)

Italy, 1953 Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

If it lacks the final fusion of purposes characterizing a masterwork, La Signora Senza Camelie is nevertheless so unmistakably and remarkably the work of a master that one is shocked to discover the rather cursory critical treatment is has generally been accorded. A frequent bone of contention is Lucia Bosè’s performance as the starlet in search of an identity –- recalling that the part was first offered, in turn, to Gina Lollobrigida and Sophia Loren, and usually implying some difficulty in accepting Bosè as a persuasive Milanese-shopgirl-turned-sex-symbol. Yet what strikes one at once today is how totally her cold, somewhat remote beauty establishes and “places” the tone of the film, clarifying her cosmic distance from the brassy world of popular filmmaking as well as the natural way in which she might become the goddess of such a realm. In anticipation of Godard’s Vivre sa vie, Antonioni brilliantly opens the film with an image of Clara seen from behind, as an anonymous pedestrian -– tracing her fingers across a move poster and then strolling down the street, the camera gliding slowly after her until she turns into the cinema entrance. Read more