Born July 24, 1944, San Mareno, California. Died May 23, 2013, Chicago, Illinois.

Here’s something I said at a special tribute to Peter held in his presence at Columbia College, on October 4, 2012:

“For me, Peter Thompson is one of those special filmmakers who reinvents cinema for his own purposes, a trait that he shares not only with people like Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer, and Jacques Tati, but also with filmmakers like Chaplin, Welles, and Kubrick.

“On some level, all of Peter’s films are mysteries and detective stories, but ones in which Peter is inviting us to join him in becoming the detectives, not in giving us puzzles that he knows how to solve but in inventing new ways for us to share in his curiosity. You might even say that part of the mysteries of his films is determining what they’re about, because in addition to reinventing cinema they might be said to reinvent things like subject matter and research as well as still more difficult-to-define entities such as poetry and history and truth.

“Peter has been a friend for about two decades, but I hasten to add that we became friends because of my enthusiasm for his early work, which existed before we ever met. A couple of years ago, we collaborated on a piece about his work, part essay and part interview, called ‘A Handful of World,’ that appeared in Film Quarterly and can also be found on my web site. And last June, I conducted a longer interview with him that was videotaped by Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, for a DVD box set devoted to Peter’s six films that I’m happy to say is currently in the works.

“In both of these interviews, Peter mentions the fact that he went through no less than 182 drafts of the script of Lowlands. This suggests to me that, for Peter, cinema is a kind of shovel, and one that invites us all to join in the adventure of his pursuit.”

***

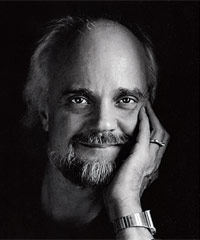

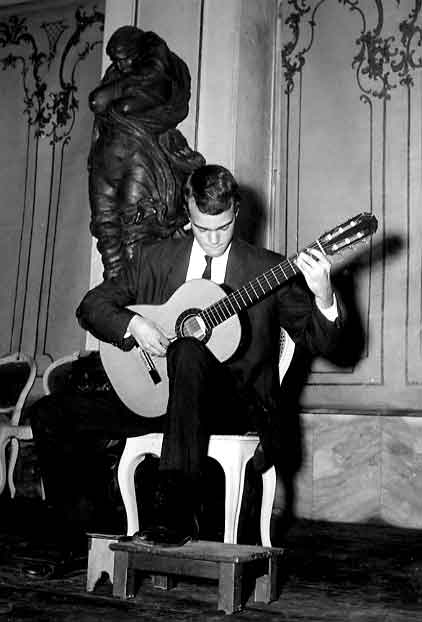

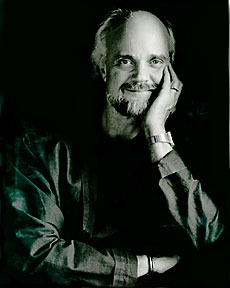

Here he is, as a teenager (performing in a recital at the Palazzo Chigi Saracini in Siena, Italy in 1962, age 18, during a four-year period of European concerts on classical guitar and studying with Andrès Segovia) and 36 years later. These are the only photos I have of him. And I think my discovery of Peter and his films was a little bit like Peter’s (and later, Mary’s) discovery of Siena — a kind of oasis, in Peter’s case for much of the last portion of his life (every summer, until his health made it impossible last year), and also a key reference in Universal Hotel and Universal Citizen, whose square (and Mary’s stride across it) becomes the first image in the former and one of the last key images in the latter.

***

I’m writing now from Sarajevo, halfway through a two-week stint of teaching (or, more precisely, presenting, discussing, and sharing) American independent and American alternative cinema at the Filmfactory, launched by the Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr this past February, with a group of sixteen filmmakers from fifteen countries (Armenia, Austria, the Czech Republic, the Faroe Islands, France, Iceland, Iran, Japan, Mexico, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S.), all between the ages of 22 and 38. It’s been a confusing but exciting first week, with much improvising in terms of scheduling and programming on a daily basis, and for me the climax so far was yesterday, Saturday morning, when, after discovering that we couldn’t use the Sarajevo Film Academy’s auditorium, ten of us met in an apartment where four of them live, between around 10 am and 2 pm.

The night before, I returned to my room in Sarajevo’s Hotel Europe (my own version of what Peter calls the “Universal Hotel”, which is almost as multicultural and as multilingual as Peter was) to find an email from Peter’s wife, Mary Doughtery, sent from Peter’s own email account:

Dear Family and Friends:

I write this email to you all with both sadness and relief. Peter passed peacefully on May 23, 2013 at 2:25 in the afternoon surrounded by his immediate family.

I want to take this opportunity to thank you all, from the bottom of my heart, for your expressions of support and love that you have showered upon us since his diagnosis 18 months ago.

I also want to invite you to attend his Memorial Service on Friday, May 31, 2013 from 5:30 to 8:30pm to be held at Peter’s beloved Columbia College, 1104 South Wabash Avenue, 8th floor Film Row Cinema.

No RSVP is necessary.

With love and appreciation,

Mary

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to The Peter Thompson Memorial Scholarship Fund at Columbia College Chicago.

***

As I recall, it was Christmas eve in 2011 when Peter and Mary had me over for dinner and Peter told me about his terminal cancer. And the last time I saw Peter was five weeks ago, April 19, when I brought over a film he might look at (Alain Resnais’ You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet), he showed me a mockup version of the aforementioned DVD box set of his complete oeuvre (six films, 251 minutes long — not long, yet over an hour longer than the complete works of Jean Vigo), and asked me if I would write his obituary.

I’m trying to fulfill that request now, but it isn’t easy. I come from and belong to the Faulknerian school of long sentences and winding drifts while Peter himself was a master of concision and economy even while he was cramming entire lives and many different worlds into each of his films. I think this is what impressed my Filmfactory colleagues the most yesterday — the capacity to suggest infinite reaches with a minimum of photographic “evidence”, carefully chosen words, and the articulation of his own voice. My plan for our viewing session was to show them first three films — a 1999 documentary about Val Lewton (two of whose features I’d screened the day before), Sara Driver’s 48-minute You Are Not I (1982), and Peter’s Universal Hotel (1986, 28 minutes) — and then let them choose what else we watched from the dozen or more DVDs I brought along from my hotel room. And it was clear right away that what they wanted to see the most was everything else I had of Peter’s that I’d brought to Sarajevo — first Universal Citizen (1986, 28 minutes), then Two Portraits (1982, 28 minutes, consisting of Anything Else and Shooting Scripts, respective portraits of Peter’s father and mother). I’m sorry now that I didn’t also bring to Sarajevo El movimiento (2003, 119 min.), his only full-length feature, as well as Lowlands (2009, 51 min.), where the status of dreams that becomes so important in his second diptych becomes even more crucial, forming even the climax of the latter film.

I think what impressed my Filmfactory colleagues above all in the four films they saw was Peter’s narration, which figures in all but the last of these — both as beautiful, sculpted writing (singled out by Mohammadreza Farzad, who translates contemporary American poetry and fiction into Farsi), and for its inherent musical form of delivery. Also for its feeling, and for what Kaori Oda described to me in a subsequent email as the “strong form” of the rhythm of his images, which made her miss Osaka and “my dear people” there and gave her “a vast space to reflect myself”.

***

Here is an outtake from our email exchanges that went into the article-interview that Peter and I collaborated on, and one that seems especially relevant here:

“Earlier, Jonathan, you mentioned the films’ voice-overs — that they seem to suppress overt emotional expressiveness in order to allow other qualities to surface. You mention ‘Bresson’ in relation to those other qualities. Let me try to amplify what you are pointing to. This style evolved during the voice-over recordings for Two Portraits. I was mortified by the first voice-over: it was so over the top, emotionally — an audience would have recoiled. I re-recorded. Again, bad — this time it flew below the emotional radar. I realized that I should try to hold the tension between those two emotional states. Five weeks and five recordings later — this time wearing earphones generating a rhythmic pulse and holding two thermoses (one whiskey, one coffee) — I had a voice-over that seemed to hold that tension. Finally! The difference — besides the positive lessons reaped from the failures — was the memory of a stunningly wonderful concert in 1966: the first visit to France by the Berlin Philharmonic since the outbreak of WWII. Herbert von Karajan conducted Mozart’s ‘Haffner’ symphony. Von Karajan stood on the podium, almost immobile, as if anxious not to deflect attention from the music’s agonizingly complicated simplicity. He hid his arms and his hands. What were visible were his back muscles. They testified to a man on the verge of exploding. The artistic and emotional power generated from his almost successfully suppressed emotion seemed to fill Chartres Cathedral. What a balancing act! The tension of that remembered experience became the goal of my subsequent voice-overs.

“This goal depends upon honed down scripts and simple writing. I remember a book by a former member of the Polish resistance about the writings of persons condemned to death under the German occupation. Under those circumstances, there exists not a single recorded case in which someone tried to express themselves beyond traditional diction and syntax. On the contrary — in every case, they simplified. In this, I’m an admirer of the style blanc practiced by the Polish post-war poets Czeslaw Milosz, Zbigniew Herbert and Wislawa Szymborska. They write ‘transparently’ with zero extra words and very few adjectives. To shrink downward to that blessed state, I write an embarrassingly large number of drafts because it takes me a while to recognize one word too many. (I’ve also handed myself an additional little hurdle in that I standardize on a fourteen-year old’s aural understanding. If a fourteen-year old kid must think about a word, and therefore lag behind the ongoing rhythm of information delivered aurally, I change it). As you join these three elements together — perceivable rhythm (even without whiskey and coffee), the ‘von Karajan paradox’, and the ‘white style’ — a miraculous effect can sometimes occur. I can’t judge in advance when, or if, it might happen, but can only recognize with gratitude when it does — suddenly, without warning, everything in the voice-over accrues into a quietly overwhelming affect. It’s not possible to point to a single word or single utterance that’s caused it. Accrual. Segovia used to say, ‘Better to move than to amaze.’ He moved with small means.”

Postscript: Peter Thompson’s complete works can be purchased at https://www.amazon.com/Peter-Thompson-Cinematic-Essays-Interviews/dp/B00F57HVPK