From the Chicago Reader (April 20, 2007). The severe sentencing of Jafar Panahi, the director of Offside, after this article was published made his remarkable (and earlier) filmmaking more vital and relevant than ever. — J.R.

BLACK BOOK ****

DIRECTED BY PAUL VERHOEVEN

WRITTEN BY GERARD SOETEMAN AND VERHOEVEN

WITH CARICE VAN HOUTEN, SEBASTIAN KOCH, THOM HOFFMAN, HALINA REIJN, WALDEMAR KOBUS, AND DEREK DE LINT

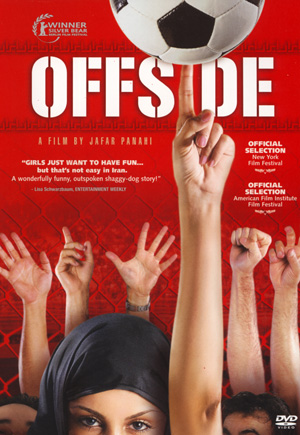

OFFSIDE ****

DIRECTED BY JAFAR PANAHI

WRITTEN BY PANAHI AND SHADMEHR RASTIN

WITH SIMA MOBARAK SHAHI, SAFAR SAMANDAR, SHAYESTEH IRANI, M. KHEYRABADI, and IDA SADEGHI

The recent successes of such films as Pan’s Labyrinth, Volver, and The Lives of Others at multiplexes is a welcome sign that art-house ghettos aren’t the only places for foreign-language films anymore. Art houses, like multiplexes, tend to foster certain expectations about the movies we go to see in them, and sometimes we miss out on what a film has to offer as a consequence. Paul Verhoeven’s big-budget drama Black Book, which opened last week at the Music Box and is now also playing at some more commercial venues, and Jafar Panahi’s low-budget comedy Offside, which opens this week at the Music Box, both confound expectations.

Black Book — about a sexy Jewish singer who poses as a Nazi to help the Dutch resistance during World War II — is a Hollywood movie in every respect but its nationality, and more professionally cast, directed, and paced than most. Offside — about a group of girls in Tehran arrested for sneaking into a World Cup qualifying soccer match between Iran and Bahrain — is closer in ambience to an American indie, but in spirit it’s almost as populist as Borat.

The New York Times‘s Manohla Dargis calls Verhoeven’s film “supremely vulgar” and “pretty much a hoot.” Up to a point I agree. It’s outrageous and provocative — after the war’s end, the heroine gets spattered with shit for collaborating — and Verhoeven’s melodramatic contrivances have inspired laughter in the past; here I’m not so sure. As someone who undervalued the political smarts of Basic Instinct and Showgirls when they first appeared, I’m probably not the best one to fault others for not taking Verhoeven seriously, but I still have to say that, ethically speaking, Black Book seems far less vulgar than a feel-good Holocaust movie like Schindler’s List. For starters, Spielberg works up loads of suspense about whether a bunch of Jewish women will be gassed at a Nazi camp, only to elicit grateful sighs of relief from us when they aren’t (the “gas chamber” turns out to be a shower). I seriously doubt that Verhoeven would ever stoop to such a ploy; he’s far less interested in stroking the middle-class sensibilities of Times readers. In fact, part of what I admire about Black Book is how it offers a kind of bracing rebuke to Schindler’s List, providing a much darker vision that refuses to let its audience off the hook so easily, though ostensibly it’s more fictional.

Verhoeven messes with our heads by exploring moral complexities that Spielberg would be happier to sweep under the rug. Some members of the Dutch resistance, for instance, turn out to be anti-Semitic, and some Nazi officials warmhearted. Sebastian Koch, the handsome German actor who plays the romantic lead in The Lives of Others, is cast here as Ludwig Muntze, head of the Dutch branch of the Gestapo. The heroine, Rachel Stein (Carice van Houten), falls for him and the movie goes out of its way to make us care about him too. (Koch himself has compared his character to Oskar Schindler.) Verhoeven claims that he and co-writer Gerard Soeteman spent 40 years researching Black Book and 20 years developing the script, and many of the details have been plucked from wartime records: Muntze is a stamp collector, for example, because the real head of the Dutch Gestapo was a stamp collector. For all its comic-book hyperbole there’s no question that Black Book is grounded in real events and that it raises real issues — above all, the messy ambiguities that wars tend to generate, as well as the degree to which, after the shooting stops, some criminals get rewarded while certain heroes end up reviled.

As with Black Book, Offside is so accessible and entertaining that some discerning viewers are suspicious of it. Even Richard Brody, whose capsule reviews in the New Yorker are usually far more sophisticated and better informed than their long reviews, finds it blandly sentimental and calls it “sweetened exoticism for export.” But what some critics are calling sentimentality may be simple humanism. Panahi refuses to make a villain out of anyone and I’m not persuaded that demonizing the mullahs who enforce gender apartheid (which bans girls from attending soccer matches, among other things) would have made us any wiser; showing the absurdity of the laws’ effects is all that’s needed.

The girls disguise themselves as boys to sneak into Azadi Stadium but are caught, arrested, and detained in a makeshift holding pen outside the arena by young soldiers who’d clearly rather be watching the match themselves. Panahi shot much of this surreptitiously on location during the actual World Cup qualifier. We stay with these two groups throughout and wind up sympathizing with the frustrations of both, though they’re often victimized in comic ways. One soldier borrows a detainee’s cell phone to call his girlfriend, arousing her jealousy when she phones back and a girl answers. Another soldier escorts one of the girls, a soccer player herself, to the men’s room shortly before halftime but is careful to mask her face with a poster of a soccer player. This builds into a sequence of almost Hitchcockian suspense, seen from the soldier’s point of view: he frantically tries to keep the men’s room clear so the girl can use one of the stalls in peace but loses track of her precise whereabouts in the process.

Portraying the soldiers sympathetically, however, isn’t the same as supporting the government. The first time I saw Offside a couple of audience members seemed offended by its celebratory use of the Iranian national anthem in the closing sequence. I later learned from Iranian friends that the version of that anthem heard here is an older, prerevolutionary one, deliberately stirring the sort of nationalistic feelings that the mullahs have been suppressing in favor of promoting pan-Islamic identity. As the director has implied in interviews, it’s important to distinguish between Iranian people — their society, after all, is extremely multicultural — and their rulers, who are as dubious as ours.

Panahi becomes more of a master with every movie, combining fiction with documentary so adroitly that we can’t tell which is which. In this respect he remains the sharpest of Abbas Kiarostami’s disciples. Kiarostami, who’s written the scripts for Panahi’s The White Balloon and Crimson Gold, opens his recent making-of documentary Around Five with TV footage of the same qualifying World Cup match — an event that has absolutely nothing to do with his own experimental Five but clearly alludes to Offside, implicitly acknowledging its importance.

One might note that Panahi applies Kiarostami’s own elliptical techniques and use of nonprofessional actors to stories with far more narrative and political momentum. He gets us to identify with all his characters, girls and soldiers alike, by showing the precise realities of their common situation. The only thing that separates them from characters in a John Hughes teen comedy is the language they speak and the laws they have to live with. But as long as American exhibitors insist on treating Offside as an art film, which it isn’t, part of that point will be lost.