From the Chicago Reader (February 10, 1995). –J.R.

Latcho Drom

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Tony Gatlif.

If you haven’t heard of Latcho Drom — an exuberant and stirring Gypsy musical, filmed in CinemaScope and stereophonic sound in eight countries on three separate continents — you shouldn’t be surprised. Although the movie has been wending its way across the planet for the past couple of years and picking up plenty of enthusiasts en route, it has at least three commercial strikes against it, any one of which would probably suffice to keep it out of the mainstream despite its accessibility. The first two of these are the words “Gypsy” and “musical”; the third is the fact that it qualifies as neither documentary nor fiction, thereby confounding critics and other packagers.

These “problems,” I hasten to add, are what make the picture pleasurable, thrilling, and important; but media hype to the contrary, sales pitches and audience enjoyment aren’t always on the same wavelength. Though this movie is so powerful you virtually have to force yourself not to dance during long stretches of it, that fact doesn’t translate easily into a 30-second prime-time spot or a review in a national magazine (though CNN did devote a four-minute feature to Latcho Drom some time ago). Released in this country by a small company in Maine aptly called Shadow Distribution, it’s been making the rounds like a faint rumor, generally without the assistance of our national drumbeaters; so when people stumble upon it it carries all the excitement of a buried treasure.

Maybe one should cite as a fourth liability the foreign title, difficult for some to remember; it means “safe journey” in Romany, the Gypsy tongue. U.S. distributors have recently balked at such “difficult” titles as Pret à Porter and The Madness of George III (the latter, I’m told, because it sounds like a sequel — a drawback that will presumably keep Shakespeare’s Richard II and Richard III off future marquees as well), changing them to Ready to Wear and The Madness of King George. An actual Gypsy phrase must sound as esoteric to them as something in Sanskrit. But this obstacle is minuscule compared to the other three.

Culture as we know it nowadays is most often defined, whether implicitly or explicitly, in national terms. (We’re apt to think of American culture as culture plain and simple, an implicit national imprint.) But Gypsy culture has no country, so we’re stuck for labels. Technically Latcho Drom is a French film — written and directed by an Algerian-born French citizen named Tony Gatlif, who has seven previous features under his belt, one of them Spanish. But existentially and aesthetically, Latcho Drom is a Gypsy film — a film about Gypsies made by a Gypsy — which means it has no nationality at all. (Not having seen Gatlif’s earlier features, I can’t characterize them in this way, though the titles of the second and third, Canta gitano and Corre gitano, suggest Gypsy subjects.) And insofar as the Gypsy experience falls between the cracks, a Gypsy movie is bound to do the same.

A Gypsy is “any member of a dark Caucasoid people originating in northern India but living in modern times worldwide, principally in Europe,” the Encyclopaedia Britannica informs us. “It is generally agreed that Gypsy groups left India in repeated migrations and that they were in Persia by the 11th century, in southeastern Europe by the beginning of the 14th, and in western Europe by the 15th century.” Broadly speaking, this last sentence provides a geographical synopsis of Latcho Drom, which begins in northern India (Rajasthan) and proceeds through Egypt, Turkey, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, France, and Spain. In each country we find Gypsies making music, and often dancing.

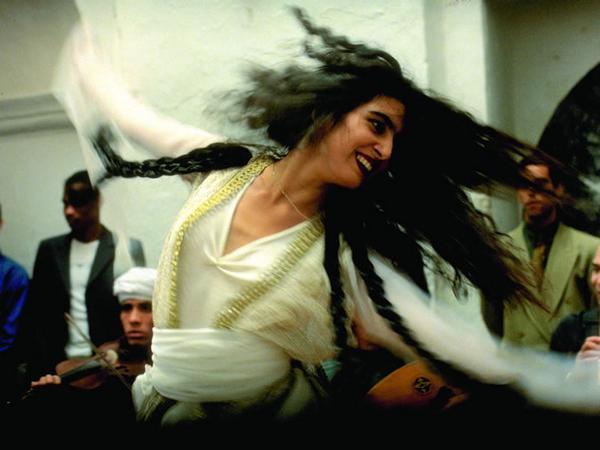

But this bald description doesn’t begin to do justice to the film’s power and subtlety, both as filmmaking and as epic narrative. Sometimes we see music and dancing emerge out of everyday work (as in India); sometimes we see Gypsies observing other performers appreciatively (as in Egypt) and then translating these music and dance idioms into their own. In a Turkish restaurant and in a rural Hungarian train station we see them performing joyously for others, and in a Romanian village and in diverse locations in France we see them playing no less infectiously for themselves. In each country we find a different kind of Gypsy music and dancing, inflected in each case by the surrounding culture: the section in France culminates in a style of jazz identified with Django Reinhardt; the Spanish finale begins with flamenco.

The Britannica also states: “All nomadic Gypsies migrate at least seasonally along patterned routes that ignore national boundaries.” This conveys the temporal side of the film’s structure, which begins in the summer and proceeds through the following three seasons. Though the film is uncluttered by dates or narration (apart from a brief passage at the very beginning), it gracefully unfolds within three simultaneous time frames: the past thousand years (tracing the Gypsy migrations from India to western Europe), the span of a single year, and 99 minutes — that is, the length of the film itself. In the process it manages to convey a wealth of information about Gypsy history and current life without any didacticism. Apart from a few song lyrics and phrases of dialogue given minimal subtitles, it tends to do without words, relying mainly on images, music, and gestures — universal languages that, like Gypsy culture itself, traverse continents and centuries.

Emotionally, the movie conveys an intense, exuberant feeling of belonging that seems intimately tied to the alienation and persecution of Gypsies — though here it’s nearly always the joy that’s emphasized, not the suffering. The only exceptions that come to mind are pointed and brief. When the camera pans past a barbed-wire fence against a snow-covered field in Slovakia, then encounters an elderly Gypsy woman singing about Auschwitz, a tattooed number visible on her forearm, we may be reminded that nearly half a million Gypsies — an estimated fourth to sixth of their total number today — were exterminated in the Nazi death camps. And when we later see Gypsies being expelled from an abandoned building in a Spanish city, and the doors and windows of the building bricked over to keep them out, we’re alerted to the external forces that keep Gypsies nomadic. (This scene leads into a climactic, soulful one in which a woman sitting on top of a barren hill sings a lyric Gatlif himself wrote: “Some evenings, like many other evenings, I find myself envying the respect that you give your dog.”) We’re reminded at times of the persecution of other peoples, such as blacks, Jews, and homosexuals, and of the emotionally rich cultures that have resulted.

But chiefly the movie celebrates, ecstatically, the Gypsy experience. As Gatlif says, “I wanted to make a film that the Roms [Gypsies] could be proud of, a film that wouldn’t make a sideshow of their misery. I wanted to write a song of praise to this people I love….I felt that if people really got to know the Gypsies, they would lose their age-old prejudices: child kidnappers, chicken thieves…

“Who cares about chickens anyway?

“Some Gypsy friends from Paris and I wanted to buy three thousand chickens with my author’s royalties, put them in two semi-trailers and set them loose at dawn on the Champs-Elysees, handing out flyers saying: ‘The Gypsies give you back your chickens!’ But we ‘chickened’ out at the thought of the poor firemen who would have to run around rounding up three thousand chickens!”

Generically speaking, Latcho Drom is a musical. But as we all know, the musical is dead — which means that this movie can’t possibly exist. How do we know that the musical is dead? Because the Hollywood propaganda machine has told us so, repeatedly. Now that the multinationals are in effect licensed to rewrite and regulate our film history, movies are restricted to the genres American studios feel equipped to make and promote, and everything else gets pushed off the sidewalk.

The industry wisdom is that the only kind of movie with singing and dancing that people will currently spend money to see is a cartoon feature. The reasons offered for this peculiar state of affairs vary. In his preface to They Went Thataway, a recent critical anthology devoted to movie genres, Richard T. Jameson mentions three other kinds of filmmaking that have edged out movie musicals in the course of explaining why he’s omitted musicals and included film noir and gangster films, the western, comedy, romance, horror, science fiction, war films, women’s films, literary adaptations, sequels, and remakes — even “the director as genre” and “the star as genre.” But musicals, he says, have “all but vanished from the modern scene”: the musical “has been run off by the rock-concert movie and the music video and, perhaps even more decisively, made redundant by the wall-to-wall song accompaniment of nonmusical films.”

This is suggestive speculation, but it ignores the fact that successful stage musicals are still produced. And when you stop to consider that each of the last few Disney animated features has topped every one of its predecessors at the box office, it’s even possible to conclude that audiences are starved for the lift that only musicals can provide. One might argue further that the only reason Hollywood filmmakers aren’t making other kinds of musicals is that they’re no longer artistically or temperamentally equipped to do so — at least according to the studio executives who would OK such projects.

So much for traditional Hollywood musicals, and what other kind is there? Here again our implicit nationalistic bias comes into play: we equate Hollywood with conventional Hollywood, conventional Hollywood with America, and America with everything else in the world, as the current execrable PBS miniseries “American Cinema” seems to do. But if we stretch the “musical” genre to include nonconcert movies that feature musical performances and/or dancing we get, for starters, Round Midnight, Bird, Mo’ Better Blues, Hairspray, Earth Girls Are Easy, The Fabulous Baker Boys, Postcards From the Edge, Bob Roberts, Life Stinks, The Thing Called Love, Immortal Beloved, and even Pulp Fiction — all of them commercial Hollywood products.

Outside that category are three recent masterpieces indebted in many ways to the aesthetics and emotional dynamics of Hollywood musicals: Terence Davies’s Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes and Chantal Akerman’s Night and Day. There’s the strange and beautiful last feature of Jacques Demy, Three Seats for the 26th, and Raul Ruiz’s mesmerizing dance spectacle Mammame (both undistributed in this country). A couple of recent Mark Rappaport videos, Postcards and Exterior Night, make exciting use of ballads, one of them brand-new. Then there are diverse classical-music musicals like Tous les matins du monde, The Piano, Un coeur en hiver, The Accompanist, and best of all The Second Heimat (which Facets Multimedia plans to make available on video). In short, you might say the musical is alive and well, though thanks to the ruling business discourse it’s in hiding. Only the conventional Hollywood musical is in eclipse.

In Latcho Drom Gatlif appropriates what might be termed the stylistic architecture of older Hollywood musicals as purposefully as the Gypsy performers appropriate “national” music and dance, proving that the same sort of elation can be achieved without pit orchestras or soundstages. When the drudgery of everyday work is turned into music and dance, as it is in the opening sequence here, we could be watching the beginning of the classic 1932 musical Love Me Tonight. And when the camera cranes up from two elderly instrumentalists into the treetops, the exhilaration is worthy of the Arthur Freed unit at MGM. For a Gypsy caravan moving through a French village at dawn, Gatlif puts together a montage of barking dogs that’s as musical as many of the numbers.

The only other attempt at a large-scale Gypsy musical that I’m aware of — Nicholas Ray’s Hot Blood (1956) — pales in comparison to this one, at least when it comes to authenticity: Cornel Wilde and Jane Russell play the lead Gypsies. Still, Hot Blood isn’t quite the debacle most accounts would have you believe. Bernard Eisenschitz in his recent invaluable Ray biography offers an interesting defense of its giddy stylistics as well as its “gaiety and energy.” Better yet, maybe someone can be persuaded to screen a decent ‘Scope print so we can judge for ourselves. It proves, along with Latcho Drom, that the stylization of the Hollywood musical and the color and vibrancy of Gypsy life can find common ground.

Another important cross-reference to Latcho Drom is Jacques Tati’s last feature, Parade. In a way the comparison is unlikely because Parade — a circus film — isn’t really a musical, doesn’t feature Gypsies, and is mainly shot on video rather than film. Yet in many crucial respects its formal procedures are the same, pointing in each case to a radical social and political position on the meaning of spectacle that is central to the film. This position is anti-Hollywood and anti-elitist in roughly equal measure, a kind of populism that rejects the usual hierarchies of class, race, and gender (as well as genre) without ever becoming esoteric or less than entertaining. In fact both movies appropriate certain aspects of popular entertainment — the circus for Tati, the musical for Gatlif — in order to redirect their energy.

Strictly speaking, Latcho Drom qualifies as neither documentary nor fiction; it freely mixes both modes in a manner reminiscent of Parade. Even more significant, both films break down the usual distinctions between performers and spectators; in every scene, being a member of the audience in the film means being an active participant in the unfolding spectacle, and by the same token, every performer becomes an audience member for other performers. Moreover, the privilege of performing is extended to every age and both genders; young and old, male and female are equally involved in the festivities, and everyone is able to become the “star” at one point or another. In both movies young children play pivotal roles as guides, witnesses, pupils, and performers. Equally striking in both movies is the use of bricolage — the appropriation of impersonal objects for personal use that enables ordinary people to reshape and reclaim their environments: the fiddling geezer in Latcho Drom who produces uncanny tonalities out of a loose violin string is the blood brother of the Parade performers who juggle paintbrushes.

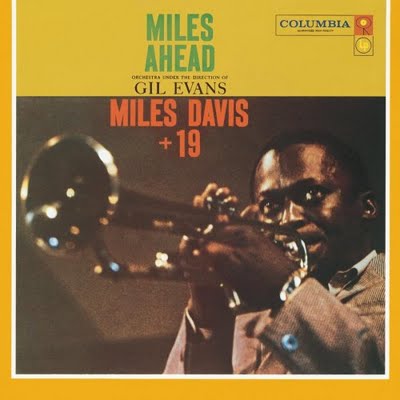

The most radical feature of both films is that the points at which a number or sequence begins and ends are usually almost impossible to determine. (A good example of this in recorded music is the album Miles Ahead, the first collaboration between Miles Davis and Gil Evans.) To define Gatlif’s mastery, one merely has to look at his remarkable and subtle transitions, which bridge countries, sequences, and sometimes the segments within a sequence — transitions that closely correspond to Tati’s own segues between onstage and offstage space and to his creative obfuscations of when a specific act or activity starts and stops. These subtle transitions subvert our usual notions of spectacle, tied to the stylization of most musicals, in which passing from “life” to the heightened reality of a particular musical number is emphasized rather than glossed over. But in this movie, as in Parade, every event has heightened reality, and never ceases to be life. Both films create an impression of unbroken poetic continuity — a continuity between life and performance that sweeps the spectator along. In the case of Latcho Drom that continuity traverses centuries and seasons as well as continents, becoming a function of nature as well as human endurance. Check it out.