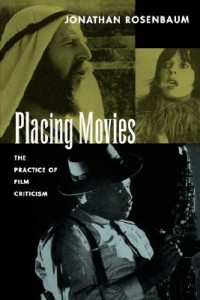

This is the Introduction to the first section of my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (University of California Press, 1993). I’ve taking the liberty of adding a few links to some of the pieces of mine mentioned here which appear on this web site. — J.R.

Introduction

Although this entire book is devoted to film criticism as a practice, this section emphasizes this fact by dealing with film criticism directly as a subject. This includes both specific examinations of the work of other critics and polemical forays into questions about how critics and reviewers operate on a day-to-day basis. A broader look at the same topic might question whether film criticism as it’s presently constituted is a worthy activity in the first place — if in fact the public would be better off without it.

I should add that it’s the institutional glibness of film criticism in both its academic and mainstream branches — above all in the United States, where it seems most widespread and least justifiable — that has led me on occasion to raise this latter question. Speaking as someone who set out to become a professional writer but not a professional film critic, I’ve never felt that movie reviewing was an especially exalted activity, but I didn’t start out with any contempt or disdain for the profession either. It was only after the institutionalizing of academic film studies got started in the early 1970s and the glamorizing of mainstream film reviewing got started a little after that that I began to wonder about whether the public was often being sold a bill of goods about the so-called “credentials” of film critics.

Admittedly, film academics had to begin by weathering both the scorn and the envy of other humanities professors, who were formerly free to handle film however or whenever they saw fit without the nuisance of specialists glancing over their shoulders. The rapidity with which academic film study developed and promulgated its own jargon undoubtedly had a lot to do with the impatience of pioneers in the field to establish their own sphere of expertise; like the difficult unison lines composed by the best of the early beboppers in 1940s jazz, this jargon was designed not only to scare off amateurs, but also to allow the “experts” to strut their stuff. Unfortunately, a grasp of this jargon didn’t necessarily have much bearing on any historical or technical or aesthetic understanding of film; it served mainly as a badge of entry for “film studies,” which often proved to be a different thing entirely.

Some of the reasons for this were initially quite positive. The absence of any firmly established canon for film studies left the field potentially wide open. But the only way this canon could grow would be if academics decided to work collectively to expand both what they knew and what was already available, and this has rarely happened. (The sheer scarcity of curiosity in the field is often breathtaking.) What’s happened instead is that film study has mainly tended to establish a canon passively and reactively — refining the discoveries of theoretical or nonacademic auteurist critics while often defining its own canon mainly on the basis of what distributors have already made available.

Similarly, as it’s usually practiced, journalistic film reviewing is a profession that has often remained dangerously close to simple news reporting (at best) and unabashed advertising (at worst), and whenever it dares to stray beyond those functions, an inordinate amount of hubris usually comes along with the presumption. Sometimes, as in the criticism of Jean-Luc Godard, this hubris turns out to be more than justified, although it’s worth adding that it’s mainly Godard’s critical intelligence as a filmmaker that created a receptive audience for his written criticism.

“Theory and Practice: The Criticism of Jean-Luc Godard” was the first piece I ever published in Sight and Sound, my favorite film magazine in English at the time, and I can recall putting an unusual amount of time into writing and rewriting it because I was aspiring to become a regular writer for the magazine. The strategy paid off, and two years later, thanks to the support of the magazine’s editor, Penelope Houston, I even found myself moving from Paris to London to become assistant editor of Monthly Film Bulletin and staff writer for Sight and Sound, which were sister publications edited from adjoining offices at 81 Dean Street for the British Film Institute. (Getting a work permit was no easy matter and took about six months of effort and patience on Penelope’s part, as well as legal help from the late Richard Roud — votes of confidence that I still feel enormously grateful for.) I remained for two and a half years; “Edinburgh Encounters” and the pieces on Ozu and Rivette in the next two sections were written during this period — the first in my life when I had steady employment as a film critic. (The second period came in 1980 — when I became a regular film and literary critic for Soho News in New York for a year and a half — and the third in 1987, when I moved to Chicago to become the film critic for the Chicago Reader, where I have been ensconced ever since.)

Almost exactly two decades after my first article appeared in Sight and Sound, when Penelope commissioned her last article from me before she departed as editor (it wound up in the Winter 1990/1991 issue), I deliberately made it a companion piece to my first, entitled “Criticism on Film,” which again dealt with “criticism composed in the language of the medium,” and concluded symmetrically with a discussion of Godard’s HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA. By that time, however, the tone of my approach to both criticism and cinema was distinctly more elegiac, and, under the circumstances, less celebratory.

***

One of the more practical of Jean-Luc Godard’s gnomic utterances might be, “Trusting to chance is listening to voices.” Film critics, who usually put their faith in chance more than they care to admit — hoping to predict audience responses and trends, “banking” on certain favorite directors and actors — tend to read and listen to one another compulsively. To a certain extent, Pauline Kael first came into prominence through attacking other critics, and although editor William Shawn got her to curb this impulse when she arrived at The New Yorker, she never lost the habit of using the responses of other viewers — friends or foes, often alluded to anonymously — as the springboards for her own polemics.

Most other critics follow suit even when the original sources of their bile (or agreement) go unmentioned. “I’m a reactive critic,” Manny Farber told Richard Thompson in a fascinating interview in the May–June 1977 Film Comment; “I like to listen to someone else and cut in.” Although my sense of Farber’s singularity as a critic — explored in an autobiographical piece that concludes this section — originally made this remark seem curious (he rarely mentioned other critics by name in his writing, and he never assigned reading in his classes), I gradually discovered that it was essential to his method, in teaching and writing alike. Whether acknowledged or not, virtually all critical discourse is part of a conversation that begins before the review starts and continues well after it’s over; and all the best critics allude in some fashion to this dialogue, however obliquely. The worst usually try to convince you that they’re the only experts in sight.

One rather grotesque illustration of this is a feeble assigned review I did of Satyajit Ray’s DISTANT THUNDER for Sight and Sound in 1975 that confused certain characters with one another, as one irritated reader wrote the magazine to point out. When I started investigating how I could have committed this gaffe, it emerged that part of my preparation for the review was reading another critic’s account of the movie at the 1973 Berlin Festival, published in the same magazine, which made the identical error. To make matters worse, two daily newspaper critics repeated the same blunder after my review appeared, which suggested that they, like me, were prone to believe more in the printed word — anybody’s printed word — than in the fleeting evidence on the screen. In just such a fashion, an enormous amount of misinformation routinely gets passed along from one critic to the next, sometimes over the span of several decades. (One would like to think that the availability of many movies on video began to put some damage control on this situation by the early 1980s.)

The same thing happens with critics copying or paraphrasing sentences cribbed from pressbooks — a practice much harder to spot and, consequently, even more prevalent, because ordinary viewers never see these publicity handouts. The one time in my career when I put together a pressbook myself — a service performed gratis for London’s Contemporary Films in 1976 to help them launch CELINE AND JULIE GO BOATING — I was amazed to find my own unsigned prose being parroted by most of the critics in town when the movie opened, even by those who detested the film.

An even more general problem rules critics’ social etiquette in admitting that they pay attention to one another. A striking difference between the behavior of critics in London and New York is that the former find many more occasions to socialize with one another, largely because the atmosphere is noticeably less competitive. After many evening press shows in London — those most commonly held for magazine reviewers, who require longer lead times — drinks and hors d’oeuvres are served, in effect inviting the critics to swap opinions and theories about what they’ve just seen. It’s always struck me as an agreeable and helpful custom — the equivalent of what one finds at most film festivals, where one’s overall sense of a critical community is also very pronounced. When I once asked a prominent American critic why this was never done in New York, his response was swift and emphatic: “You can’t talk about a film right after you’ve seen it — other critics will steal your ideas!”

It was hard to explain to him that in London, where ideas are less likely to be seen as private property, critics are often delighted if their ideas are stolen, because this means that their ideas have power. In New York, only the critics are supposed to have power, and the ideas have to fend for themselves. This creates a different notion of criticism, a different notion of community, and a different notion of ideas. It also helps to explain why film critics are regarded as stars in America — a situation that has only existed since the 1970s — but nowhere else. (At the moment a critic becomes a star, the critical discourse becomes a nightclub act.) To be a star means to have an aura, and in a media ruled by the marketplace, auras are strictly personal possessions, not to be shared.

What seems most ironic about this is such auras always depend more on institutional bases than they do on ideas, expertise, or even personalities. As writer-director Samuel Fuller once put it to me with characteristic bluntness and lucidity, “If Vincent Canby got fired from the Times today, and he went to a bar and started talking about a movie he’d just seen, nobody there would give a fuck what he thought. They’d probably just tell him to shut up.”

This helps to dramatize the fact that authority in matters of film judgment is often an illusory construct — a point emphasized in my piece on Béla Tarr. (Seeing a particular movie because “the Times says it’s good” means in effect trusting not Canby but the people who hired him — and what do they know about movies? — as well as all the traditions and particular interests that The New York Times embodies, for better and for worse.) Public opinion of a given movie generally grows out of a general “buzz” that circulates around it, and publicists, reviewers, and audiences — usually in that order — all contribute to that drone and influence each other in the process. The buzz usually starts well before the picture’s release and grows (or dies) over many weeks afterward, and the cacophonous overlaps that compose it often make it hard to determine which voices are the most dominant or influential.

***

Although I’ve omitted my earliest pieces for Film Comment, I’ve included extracts from my “Journals” (from Paris, London, and elsewhere) for that magazine from the mid-1970s which represent for me today some of the best as well as some of the worst tendencies of that column. (For purposes of illustration, I ask for the reader’s indulgence; the commentary on film criticism is more fleeting here than elsewhere in this section.) Although the freedom granted me by Richard Corliss and the personal-confessional mode I adopted enabled me to spread my nets fairly widely — eventually leading to a kind of research and writing in Moving Places that took me outside reviewing entirely — it also fostered a certain intolerance and belligerence that probably reached its shrillest level in my “London and New York Journal.” Some of this undoubtedly grew out of a sense of impotence and ineffectuality in relation to American film culture which was only exacerbated by my years of living abroad. When I was living in New York during the 1960s, one could count to some degree on such writers as Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael for a defense of a certain intellectual approach toward cinema; but as their audiences grew, their intellectual partisanship tended to wane, and the philistinism and xenophobia that seemed to me on the rise in New York film criticism often sent me into intemperate rages.

Here’s a characteristic sentence from my May–June 1977 column — entitled, like the ones immediately following it, “Moving,” and written while I was in the process of moving from London to San Diego, shortly after a brief trip to Paris: “The first indication I had that Alain Resnais’ PROVIDENCE might be something special — apart from the enthusiasm of the French press — was the report that most Manhattan critics hated it.” It was undoubtedly remarks of this kind that eventually led Andrew Sarris to write (in the January–February 1978 Film Comment): “I have been disturbed for some time by a note of unending apologia in [Robin] Wood’s writing for Film Comment, particularly in apposition to the boringly relentless pugnacity of Jonathan Rosenbaum.”

This was undoubtedly one of the periods in my career when my writing habits were proving to be most irksome to some of my colleagues. In the 22 October 1976 issue of the [London] Times Educational Supplement, Wood himself had already gone further than Sarris would later and virtually linked me to the downfall of Western civilization — specifically for some flip comments comparing moviegoing and sex apropos of CELINE AND JULIE GO BOATING in London’s Time Out, and for the nature of my praise of FAMILY PLOT in my “London and New York Journal,” which Wood saw as being darkly related: “The implicit trivialization of art and life is the ultimate stage in our alienation,” he concluded.

This scarcely begins to describe some of the repercussions that my anger in print was having, and not only among active critics. To cite another example, the 27 March entry in my “London and New York Journal” provoked a distressed letter half a year later from François Truffaut, whom I had been working with at the time — I was translating André Bazin’s Orson Welles for Harper & Row, and had been serving as both editor and translator on a lengthy preface that Truffaut was writing for that book. (For those who want to read that letter and follow our ensuing exchange, see pages 461–464 in Truffaut’s Letters [Faber and Faber, 1989].) And it’s possible that the closing two sentences of the same two paragraphs permanently prevented any rapprochement or future friendship between myself and Pauline Kael, whom I had already undoubtedly alienated by writing an attack on her essay “Raising KANE” for Film Comment four years earlier.

I can’t say I look back on my former venom with pride — some of it is stridently over-the-top and unpleasantly self-righteous, although I still agree with most of the positions I took. What surprised me at the time, however, and continued to surprise me for years afterward, was that established critics with vastly more power and influence like Kael and Sarris would be as unforgiving as they were about the criticism of a relatively unknown upstart like myself.

In the case of Kael, the first time we met face to face, and then only briefly, was at the New York Film Festival in 1978; both before and after that, mutual friends advised me that I could never hope to become friends with her because of what I’d written about her. I had wrongly assumed that because she’d been so merciless herself about attacking others at the start of her career that she’d be a good sport about being at the receiving end. In fairness to Pauline, however, I should report that after I became a member of the National Society of Film Critics in 1989, she came up to me at the end of the next annual meeting and told me that she had voted for me because (I quote from memory) “no one else has attacked me so consistently over the years.” I laughed and replied, “That’s because no one else has read you so consistently over the years.” The following year — the last meeting she attended before retiring — she was kind enough to tell me that she had only been kidding the previous year and that there were other good reasons to have voted for me.

As for Andy, who was never very fond of polemics to begin with, I’ve been told that he refused to speak to me for a couple of years in the early 1980s because of some critical remarks I had written about him in my entry on Erich von Stroheim in Richard Roud’s Cinema: A Critical Dictionary — an entry I had written six or seven years earlier. In recent years, I should add, he’s been friendly. This paragraph, of course, may conceivably lead him to cut me again, but I should stress that I’m less interested here in settling old scores — or opening old sores — than in revealing to disinterested students the prices that have to be paid sometimes for speaking one’s mind in print, especially when it concerns critics in the New York area.

***

A final note on “A Bluffer’s Guide to Béla Tarr,” the first of a dozen of my Chicago Reader columns included in this book. As with my other Reader reviews reprinted here, I have retained their original formats, including the star ratings, because I consider these to be inextricably tied to their meanings. (I’ve adopted the same principle for my Monthly Film Bulletin review in the next section.) The explanation of these ratings, printed in the Reader with each review, is “**** = Masterpiece, *** = A must-see, ** = Worth seeing, * = Has redeeming facet, and 0 = Worthless.” Star ratings tend to be common currency in Chicago film reviewing, and it’s a system I inherited when I started working at the Reader.