From the November 1, 1993 Chicago Reader. This is my favorite Hou Hsiao-hsien feature. –J.R.

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s masterpiece about the childhood and early adulthood of octogenerian Taiwanese puppet master and actor Li Tien-lu. This is the second part of a trilogy about Taiwanese life in the 20th century, covering all but the first few years of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan (1895-1945). Hou’s preference for filming entire scenes in long takes from fixed camera angles and for eschewing close-ups has never been as masterfully employed and modulated as it is heresome of the landscape shots are breathtaking. The film alternates between re-created scenes from Li’s life, Li speaking directly to the camera about his past, and extracts from his puppet and stage performances, creating a layered density in the narrative that does full justice to the complexity and poetry of Hou’s investigation. In Mandarin and Taiwanese with subtitles. 142 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the July 1, 1993 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

More mud pies and occasional musical numbers from Mel Brooks in his parodic Blazing Saddles mode (has he any other?) — predictably slapdash but indefatigably good-natured and sometimes funny to boot. Completely disregarding the PC guidelines of left and right alike, this medieval romp features gags about Jews, blacks, gays, blind people, and the clergy, among others, but none of it seems mean spirited. Dom DeLuise does a very funny impersonation of Brando impersonating Don Corleone; with Cary Elwes, Amy Yasbeck, Isaac Hayes, Roger Rees, Tracey Ullman, and Brooks himself as a rabbi. Evan Chandler and J. David Shapiro collaborated with Brooks on the script. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 10, 1993). — J.R.

The least known, though far from least interesting, of producer Val Lewton’s exemplary, poetic B-films, this was withdrawn from circulation for nearly half a century due to an unjust plagiarism suit that Lewton had the misfortune to lose. Like many of Lewton’s best efforts (Cat People, I Walked With a Zombie, The Leopard Man), this is a taut thriller promising fantasy in its title but offering a dark look at human psychology that becomes even more disturbing through what’s left to the viewer’s imagination. The plot concerns a young third mate (Russell Wade) on a cargo ship who’s befriended by a lonely captain (Richard Dix), whom he gradually discovers is a disturbed tyrant with little of the self-confidence he initially shows — a cracked father figure whose crew is mysteriously loyal in spite of his weaknesses. Like Lewton’s other early pictures, it’s carefully scripted (by Donald Henderson Clarke), efficiently directed (by Mark Robson), and evocatively shot (by Nicholas Musuraca). This 1943 “second feature” boasts a large and well-defined cast of characters and a very involved plot, though it lasts only about 70 minutes — there’s scarcely a wasted motion, a bracing object lesson to nearly all feature makers today. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 2, 1996). — J.R.

Trainspotting

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Danny Boyle

Written by John Hodge

With Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller, Kevin McKidd, Robert Carlyle, Kelly Macdonald, and Susan Vidler.

It would be pushing it to call Trainspotting a serious work of art or a major statement about anything, but as an edgy, artful piece of entertainment it beats any Hollywood release of the summer by miles. That isn’t much of a compliment. The awfulness of the current crop of “big” (i.e., extensively advertised) summer movies has been so unprecedented that when people ask me how I could find anything halfway nice to say about The Rock and Independence Day, I can only refer them to the even worse dreck they were fortunate enough to miss. Context changes everything: at Cannes, where I first saw Trainspotting, there were at least nine other movies I liked more, and perhaps another seven or eight I liked as much. But in the context of commercial movies this summer, the film unquestionably shines.

Adapted from a 1993 novel by Irvine Welsh, who has a cameo in the movie as a drug dealer, Trainspotting was created by the same team that turned out the much less interesting Shallow Grave: producer Andrew Macdonald, director Danny Boyle, writer John Hodge, lead actor Ewan McGregor, and the same cinematographer, production designer, and editor. Read more

From The Soho News (October 27, 1981). — J.R.

It’s no surprise that My Dinner with André (loved by Vincent Canby), now on at the Lincoln Plaza, was one of the most popular films at the New York Film Festival — or that Lightning Over Water (hated by Canby), and now on at the Public, was one of the least popular. It isn’t just that the former movie says something that many of us want to hear, and says it well — nor that the latter says something that few of us want to hear, and says it problematically.

Each movie stars two artists who work in the world of make-believe, playing themselves, and yet the respective positions each pair takes in relation to playing this game couldn’t be more different. For André, director Louis Malle worked from a script by the two performers, playwright/actor Wallace Shawn and stage director André Gregory. For Lightning, film directors Wim Wenders and the dying Nicholas Ray almost concurrently wrote and directed their own performances, after a fashion.

Having once played myself in a film (Peter Bull’s The Two-Backed Beast, or The Critic Makes the Film), at the same time that I was writing a critical memoir that allowed me to play myself in a book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies), I can well appreciate the subjective factors that enter into any exercise in self- representation. Read more

The following was commissioned by and published in Frank Tashlin, edited by Roger Garcia and Bernard Eisenschitz, Éditions du festival international du film de Locarno, 1994. — J.R.

“According to Georges Sadoul, Frank Tashlin is a second-rank director because he has never done a remake of You Can’t Take It With You or The Awful Truth. According to me, my colleague errs in mistaking a closed door for an open one. In fifteen years’ time, people will realize that The Girl Can’t Help It served then — that is, today — as a fountain of youth from which the cinema now — that is, in the future — has drawn fresh inspiration ….To sum up, Frank Tashlin has not renovated the Hollywood comedy. He has done better. There is not a difference in degree between Hollywood or Bust and It Happened One Night, between The Girl Can’t Help It and Design For Living, but a difference in kind. Tashlin, in other words, has not renewed but created. And henceforth, when you talk about a comedy, don’t say ‘It’s Chaplinesque’; say, loud and clear, ‘‘It’s Tashlinesque’.“

Jean-Luc Godard’s review of Hollywood or Bust in the 73rd issue of Cahiers du cinéma (July 1957) is founded on a frank prophecy, only a small part of which has come true. Read more

To celebrate the showing of the restoration of Sara Driver’s You Are Not I at the New York Film Festival this Thursday (October 6), here is the chapter of my still-in-print book Film: The Front Line 1983 devoted to Sara, this film in particular. I’m also happy to report that early next year (or thenabouts), Sara’s complete works to date will be released in a long-overdue DVD box set in Canada by Ron Mann’s Sphinx Productions. A video interview I did with her about When Pigs Fly will be one of the extras.– J.R.

SARA MILLER DRIVER

Born in New York, 1955

1979 –- Dream Gone Bad (16mm, b&w, 2 min., silent)

(unavailable)

1980 -– Death in Hoboken (16mm, b&w, 3 min.) (unavailable)

Sir Orpheo (16mm, b&w, 18 min.) (unavailable)

1982 – You Are Not I (16mm, b&w, 48 min.)

If Sara Driver is the youngest filmmaker included in this survey, You Are Not I does not convey that impression. In this respect, it represents a quantum leap from a student exercise like Death in Hoboken, which is the only previous film by Driver that she’s been willing to show me.

A sketchy thriller chase ending in a murder, staged in and around the decrepit atmospherics of Hoboken’s Erie-Lackawanna Railway Terminal, the earlier effort, shot in high-contrast photography, resembles an arty fragment of something like Orson Welles’s The Trial, or, perhaps closer to the mark, Arthur Penn’s Mickey One. Read more

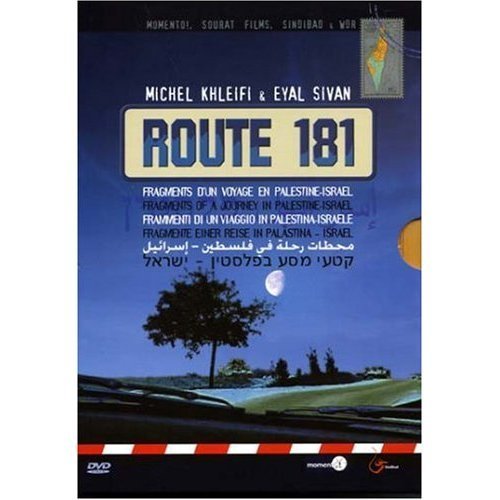

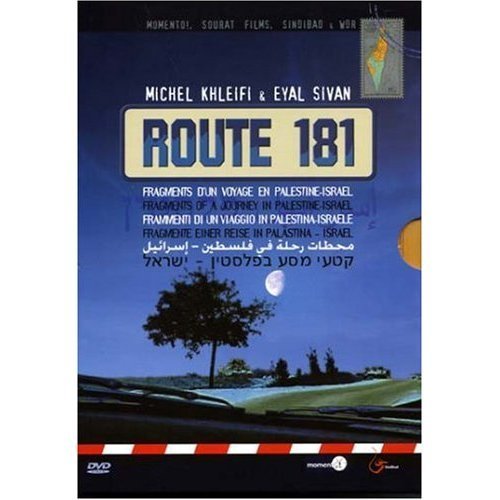

We’re human, unlike the Arabs, says an Israeli soldier in this 2003 documentary. The remark sums up the bias of Western media in covering Baghdad and the West Bank, a bias that makes this an eye-opening experience. Named after United Nations Resolution 181 (which divided Palestine into two states in 1947), the film is a road diary following the two directors, Michel Khleifi of Palestine and Eyal Sivan of Israel, along the resulting boundary; it gets closer to the everyday facts of Arab-Jewish relations in all their complexity than any other documentary I’ve seen. Its three discrete parts — covering the south, the center, and the north — run 84 minutes each and can be seen in any order. (JR) Read more

From the June 24, 2005 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Me and You and Everyone We Know

*** (A must see)

Directed and Written by Miranda July

With John Hawkes, July, Miles Thompson, Brandon Ratcliff, Carlie Westerman, and Natasha Slayton

Or

*** (A must see)

Directed by Keren Yedaya

Written by Yedaya and Sari Ezouz

With Dana Ivgi, Ronit Elkabetz, Meshar Cohen, Katia Zinbris, and Shmuel Edelman

Samaritan Girl

no stars (Worthless)

Directed and written by Kim Ki-duk

With Kwak Ji-min, Seo Min-jeong, Lee Eol, Hyun-min Kwon, and Young Oh

“Sex is Confusing” could serve as an alternate title to these three movies, all high-profile film festival prizewinners. The first is an American woman’s debut feature, the second an Israeli woman’s first feature, and the third is Korean director Kim Ki-duk’s tenth.

Miranda July’s account of the inspiration for Me and You and Everyone We Know gives an indication of her wistful comedy’s strengths and limitations. “This movie was inspired by the longing I carried around as a child, longing for the future, for someone to find me, for magic to descend upon my life and transform everything,” she writes in the press packet. “It was also informed by how this longing progressed as I became an adult, slightly more fearful, more contorted, but no less fantastically hopeful.” Read more

From the Monthly Film Bulletin, no. 502, November 1975. — J.R.

OHAYO (GOOD MORNING)

Japan, 1959

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Cert — U. dist — Cinegate. p.c — Shochiku/Ofuna. p — Shizuo Yamanouchi. sc — Yasujiro Ozu, Kogo Noda. ph — Yushun Atsuta. col — Agfacolor. ed —Yoshiyasu Hamamura. a.d —Tatsuo Hamada. m — Toshiro Mayuzumi. l.p — Chishu Ryu (Keitaro Hayashi), Kuniko Miyake (Tamiko Hayashi), Yoshiko Kuga (Setsuko Arita, Tamiko’s Sister), Koji Shidara (Minoru Hayashi, Older Son), Masahiko Shimazu (Isamu Hayashi, Younger Son), Keiji Sada (Heichiro Fukui, English Teacher), Haruo Tanaka (Pencil Salesman), Haruko Sugimura (Mrs. Haraguchi), Miyaguchi (Mr. Haraguchi), Eiko Miyoshi (Mrs. Haraguchi’s Mother), Eijiro Tono (Tomizawa), Teruko Nagoako (Tomizawa’s wife), Sadako Sawamura (Mrs. Okubu), Kyoko Izum and Hasabe (Couple with TV Set), Toyo Takahashi. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1975).

I was shocked to learn yesterday [in December 2011] of the death of Gilbert Adair, a close friend during the mid-70s (when both of us were living in Paris, and for some time later, after I moved to London ahead of Gilbert). This collaborative article, which I instigated, assigning the middle sections to Gilbert and to Michael Graham (also, alas, no longer alive), is being posted now in memory of our friendship. (With Lauren Sedofsky, Gilbert and I had also already collaborated on an interview with Rivette the previous year, which was posted here yesterday.) And because of the unusual length of this article, I’m running it in two parts; the first half, with sections by me and Gilbert about Duelle, appeared a few hours ago. — J.R.

3

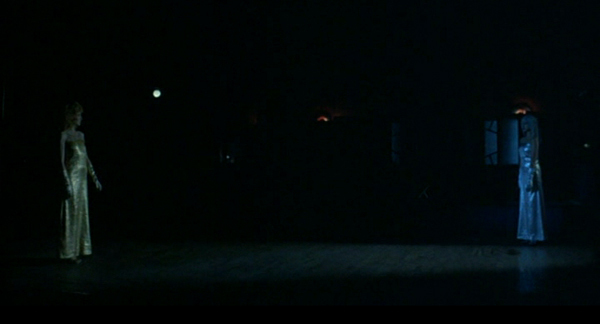

Like any Rivette film, Le Vengeur (2) took shape gradually, drawing on a large number of deliberately chosen ideas and as many fortuitous circumstances. As important as Rivette’s interest in Tourneur’s The Revenger’s Tragedy (drawn to his attention by Eduardo De Gregorio), and the curious traditions surrounding the period of Carnival, was the availability of Geraldine Chaplin and Bernadette Lafont together with that of a group of dancers from Carolyn Carlson’s company. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1975).

I was shocked to learn of the death of Gilbert Adair, a close friend during the mid-70s (when both of us were living in Paris, and for some time later, after I moved to London ahead of Gilbert). This collaborative article, which I instigated, assigning the middle sections to Gilbert and to Michael Graham (also, alas, no longer alive), is being posted or reposted in memory of our friendship. (With Lauren Sedofsky, Gilbert and I had also already collaborated on an interview with Rivette the previous year, which was posted here yesterday.) And because of the unusual length of this article, I’ll be running it in two parts; the second half, with sections by me and Michael Graham about Noroît, will appear a few hours from now. — J.R.

In theory, from the vantage point of early spring, it would go something like this: four movies to be shot consecutively, each one an average-length feature to be filmed in three weeks; editing to begin after the fourth is shot, the four films edited in the order of their successive releases. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 25, 1997). — J.R.

Sling Blade

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Billy Bob Thornton

With Thornton, Dwight Yoakam, John Ritter, J.T. Walsh, Natalie Canerday, Lucas Black, James Hampton, Rick Dial, and Robert Duvall.

There is no point in rendering something realistically unless it is to make it more meaningful in an abstract sense. In this paradox lies the progress of the movies. — Andre Bazin

In one of the unfortunate casualties of film history and criticism, writer-director-performers are generally approached as performers and/or directors first and as writers second, yet it’s often the writerly impulse that gives birth to both the performance and the direction. Erich von Stroheim and Charlie Chaplin are seldom regarded as the writers of Foolish Wives and City Lights respectively, but without their scripts neither the performances nor the films themselves would exist. Orson Welles, habitually described as a director and actor, insisted throughout his career that he always started with the written word, not with free-floating ideas for “shots.”

So it was a matter of some satisfaction to me that Billy Bob Thornton wound up getting an Oscar last month not for his lead performance in Sling Blade or for its direction but for his script. Read more

A reclusive, old-fashioned, intellectual novelist and widower living in London (John Hurt) stumbles accidentally into a screening of Hotpants College II at his local multiplex and becomes hopelessly, obsessively enamored of one of its young American stars (Jason Priestley). Fan magazines and the purchase of a VCR fail to satisfy his longings, so he travels to the Long Island town where his beloved resides and plots to encounter him in the flesh. This perfectly realized, beautifully acted, sweetly hilarious 1997 first feature by English writer-director Richard Kwietniowski, adroitly adapted from Gilbert Adair’s short novel of the same name (a comic variation on Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice”), is a witty, canny meditation on the power of pop culture in general and the rationalizations of cinephilia and film criticism in particular. What makes it perhaps even better than Adair’s clever novel, which is somewhat limited by its first-person narration, is the beautiful balance of humane sympathies Kwietniowski achieves; at no point does the foolishness or vanity of either character wipe out our sense of his dignity, and Fiona Loewi is no less touching as the movie star’s girlfriend. A “small” film only in appearance, this is as solid and confident as any first feature I’ve seen this year. Read more

From the November 10, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

THE BEAR

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud

Written by Gerard Brach

With Douce, Bart, Jack Wallace, Tcheky Karyo, and Andre Lacombe.

Much of the immediate appeal of Jean-Jacques Annaud’s new feature, apart from its impressiveness as a technical feat, is the attraction of seeing animals more than people, which also means seeing a movie that’s virtually free of dialogue. In theory, at least, there’s something relatively uncorrupted about both experiences. We spend so much time watching actors in the media — people pretending to be what they’re not — that there’s something refreshing about watching animals being animals for a change, even when they are “acting” in a fiction film. Similarly, the sparsity of dialogue — a total of 657 words shared by three actors in 93 minutes — brings us close to the purity of silent film and its strictly visual means of story telling, which produces that primal sense of unfolding narrative that most talkies miss. (Following a belt-and-suspenders principle when it comes to using dialogue and image, the average sound movie puts forth a redundancy of information and effect that leaves less freedom for the spectator’s imagination than the average silent movie.) Read more