To celebrate the showing of the restoration of Sara Driver’s You Are Not I at the New York Film Festival this Thursday (October 6), here is the chapter of my still-in-print book Film: The Front Line 1983 devoted to Sara, this film in particular. I’m also happy to report that early next year (or thenabouts), Sara’s complete works to date will be released in a long-overdue DVD box set in Canada by Ron Mann’s Sphinx Productions. A video interview I did with her about When Pigs Fly will be one of the extras.– J.R.

SARA MILLER DRIVER

Born in New York, 1955

1979 –- Dream Gone Bad (16mm, b&w, 2 min., silent)

(unavailable)

1980 -– Death in Hoboken (16mm, b&w, 3 min.) (unavailable)

Sir Orpheo (16mm, b&w, 18 min.) (unavailable)

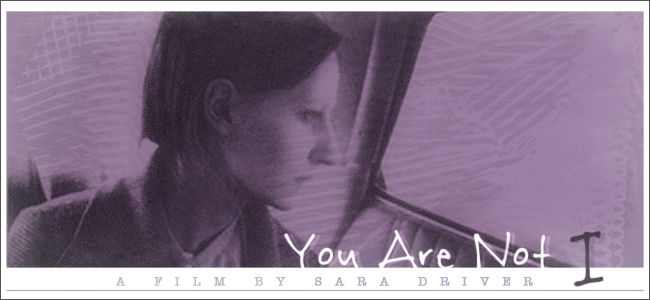

1982 – You Are Not I (16mm, b&w, 48 min.)

If Sara Driver is the youngest filmmaker included in this survey, You Are Not I does not convey that impression. In this respect, it represents a quantum leap from a student exercise like Death in Hoboken, which is the only previous film by Driver that she’s been willing to show me.

A sketchy thriller chase ending in a murder, staged in and around the decrepit atmospherics of Hoboken’s Erie-Lackawanna Railway Terminal, the earlier effort, shot in high-contrast photography, resembles an arty fragment of something like Orson Welles’s The Trial, or, perhaps closer to the mark, Arthur Penn’s Mickey One. The only original touch in the film is the use of the soundtrack of a 1950s jazz album featuring added sound effects – a record whose odd percussive effects create a certain zone of narrative ambiguity about the possible proximity of the pursuing to the pursued inside the station. It’s an interesting uncertainty, because given the film’s stylistic aggressiveness and use of subjectivity (the viewpoint is basically that of the man being followed), there’s no objective way of distinguishing narrative fact (the off-screen, approaching heavy) from expressive commentary (the fear or possibility of same). Significantly, it’s the same sort of ambiguity in relation to the heroine’s schizophrenia in You Are Not I that structures our entire reading of the latter film.

Closely adapted from a Paul Bowles short story written in the late 1940s, Driver’s featurette is adequately synopsized by the filmmaker herself in a publicity handout:

…It is the story of a young woman, Ethel, who escapes from a mental hospital during the chaos of a multiple-car accident. She is mistaken for a shock victim by a rescue volunteer who finds her trying to place a stone in a dead woman’s mouth. The volunteer drives her to her sister’s house. The sister is confused and angered by the sudden arrival of the psychotic Ethel. Not wishing to be alone in the house with her, the sister brings two neighbor women over. Finally the sister calls the hospital and finds out that Ethel “wasn’t released at all but somehow got out.” They nervously await the attendants from the hospital while Ethel, refusing to speak, formulates a plan to stay in the house. The women are terrified of her and are relieved when the attendants arrive. As Ethel is being ushered out by the men, she takes one of the stones out of her pocket and thrusts it into her sister’s mouth. The screen goes black. As it clears, the sister is being taken away while Ethel remains in the house: “For a moment, I could not see very clearly, but even during that moment I saw myself sitting on the sofa. As my vision cleared I saw that the men were holding my sister’s arms and she was putting up a terrific struggle. The strange thing, now that I think about it, was that no one realized she was not I.”

Given the overall look of the film, and the meticulously layered construction of the sounds and images alike, it isn’t surprising that Jean-Marie Straub became an enthusiastic partisan of this film after seeing it at the Rotterdam Film Festival in early 1982. (“I liked your film ten times better than Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe movies,” he told Driver.) As in many of the heroic and mock-heroic compositions of Straub and Huillet, bodies are juxtaposed against landscapes (a row of sheet-covered corpses beside a road actually evokes Machorka-Muff and Not Reconciled in its eerie beauty – although the arrival of a couple of vans in the same shot suggests [James] Benning), off-screen voices against on-screen fictions, surrealist fantasies of the unbridled ego against documentary representations of its confinement, and momentary subjective flashes against longer and broader meditations (e.g., the powerful movement from still shots of two old women pressed against a wire fence to a plan-séquence that starts with Ethel (Suzanne Fletcher) walking past them – like a quick journey from Marker’s La jetée to Antonioni’s La notte). The divided self – the art and craft of schizophrenia – thus becomes the film’s method as well as its subject, and the fierce battle of wills, world-views, and intelligences between the two sisters dictates the formal separations in Driver’s stark approach.

|

|

|||||

|

In effect, You Are Not I begins more or less the way that Psycho ends – with a schizophrenic in closeup remaining absolutely still while explaining everything off-screen. That the shot of Fletcher, unlike the shot of Anthony Perkins in Psycho, is actually a still, creates an effect of ambiguity that the remainder of the film builds upon: because of our expectation of movement, we may initially read the still as a moment recorded on film rather than a split-second – a moment during which Fletcher is making herself as motionless as possible. In comparable fashion, the periodic uses of blackouts in the film and the synthesizer effects and music (by Phil Kline) foreground the properties of light and sound as willful constructions, highlighting the manner in which Ethel as a schizophrenic becomes the master of her fate by conjuring up the world around her.

Insofar as it uses narrative ambiguity and foregrounds some of its formal elements, You Are Not I demands a certain amount of collaborative work from the spectator. At the same time, it adopts the method of a Poe story, which requires the virtual submission of the reader/spectator to the will and power of the narrative voice. Nevertheless, he film implies that between the sisters we ultimately have to take sides – and it goes to great pains not to make that choice an easy one. The picture of domestic normality conveyed through Ethel’s sister and her neighbors is almost as terrifying as the family dinner in Eraserhead, but the complacency of Edith is not very easy to accept, either. Driver told me that she saw the conflict between the sisters as basically territorial, and directed the actresses accordingly. (She asked Melody Schneider, who played Sister – and who, incidentally, was only 22 when the film was shot, although the character seems almost twice as old -– to bring things of her own to the set that were precious to her in order to make her feel more territorial towards the house. Driver also apparently rehearsed her off-screen daily routines with her so that Ethel’s arrival would be felt more as a disruption.)

The film was shot by Jim Jarmusch, on whose Permanent Vacation and the more recent Stranger Than Paradise Driver served as production manager. [2011 correction: In fact, Driver served as producer on the latter feature.] Otherwise, her background in film, apart from New York University’s graduate film school (where she made You Are Not I on a $14,000 budget thanks mostly to scholarship grants), is not very extensive. In college, her main interests were theater and archeology; her junior year was spent at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, and during her senior year – at Rudolph Macon Women’s College, in Virginia – she wrote and directed a play about Zelda Fitzgerald called “What the hell”—Zelda Sayre. This may help to account for the surprising fact that the only conscious filmic influence exerted on Driver when she made You Are Not I was Cassavetes’ A Woman Under the Influence. (“I think it’s because of the study of timing between people in that film,” She told me. “It’s not stylistic, it’s just a gut emotional reaction – and wanting to involve an audience that much.”) More recently, she cites as the two films that have most impressed her Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Tarkovsky’s Stalker, both of which might be regarded as archetypes of the European art film. Whether or not that tradition has a viable future in this country, Driver is clearly a filmmaker to watch; it’ll merely be our bad fortune if we have to cross the Atlantic in order to see her future work.