From the November 10, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

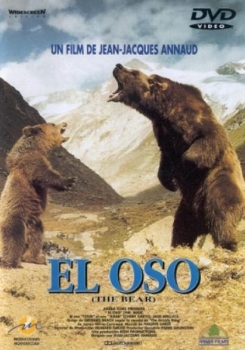

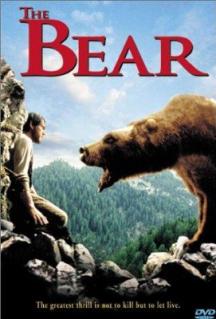

THE BEAR

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud

Written by Gerard Brach

With Douce, Bart, Jack Wallace, Tcheky Karyo, and Andre Lacombe.

Much of the immediate appeal of Jean-Jacques Annaud’s new feature, apart from its impressiveness as a technical feat, is the attraction of seeing animals more than people, which also means seeing a movie that’s virtually free of dialogue. In theory, at least, there’s something relatively uncorrupted about both experiences. We spend so much time watching actors in the media — people pretending to be what they’re not — that there’s something refreshing about watching animals being animals for a change, even when they are “acting” in a fiction film. Similarly, the sparsity of dialogue — a total of 657 words shared by three actors in 93 minutes — brings us close to the purity of silent film and its strictly visual means of story telling, which produces that primal sense of unfolding narrative that most talkies miss. (Following a belt-and-suspenders principle when it comes to using dialogue and image, the average sound movie puts forth a redundancy of information and effect that leaves less freedom for the spectator’s imagination than the average silent movie.)

The Bear‘s story, adapted by Gerard Brach from The Grizzly Bear, a novel by James Oliver Curwood published in 1916, can be encapsulated in the four lines presented by Annaud to producer Claude Berri seven years ago: “An orphan bear cub. A big solitary bear. Two hunters in the forest. The animals’ point of view.” If Annaud had followed this plan rigorously — and for reasons that I will soon address, it’s hard to see how he could — he might have wound up with a film as luminous and as irreducible as what he was trying for. The idea of telling the story from the bears’ point of view is a pretty appealing one, but the film’s opening title — “British Columbia, 1885” — already suggests that it’s an unrealizable one as well, unless we postulate a couple of bears who can recognize maps and calendars.

In fact, the apparent viewpoints of the orphan cub and the big solitary bear — mainly that of the former — do form part of the story, but only a part. In this respect the animated Bambi actually comes closer to showing humans from the viewpoint of animals (even though the Disney feature is shot through with an anthropomorphism that The Bear mainly seeks to avoid), because the Disney movie denies the humans any language of their own. The Bear‘s opening title and 657 words may not seem like much, but they’re more than enough to establish a frame of reference that is completely foreign to the bears, and the effect of this verbiage is so intrusive and destructive to the film’s higher aims that it’s difficult to understand why Annaud and Brach included it; certainly the story as a whole could have been told nearly as well without any words at all.

On the other hand, it’s surely utopian to assume that a film of this kind, even one without words, could register a strictly nonhuman viewpoint, much less establish one. (I’m reminded of Andrew Sarris writing many years ago of Jacques Tati’s Playtime as a “nonhuman comedy,” which raised some speculation about what such a term could possibly mean: a comedy made by a Martian, perhaps?) Even if such a viewpoint could be expressed, it’s questionable whether any of us would recognize it as such. We — adults and small children alike — have already been inundated by views of nature that are anything but pristine or Edenic. (Even if we haven’t seen any TV, we’ve all encountered animal dolls or Disney products or advertisements that anthropomorphize the nonhuman.) Attempting or at least pretending to take a position toward nature that is outside of culture only means submitting less consciously to cultural conditioning.

This isn’t to say that The Bear sentimentalizes nature as ruthlessly as Disney cartoons do; on the contrary, it occasionally allows us glimpses into the sort of animal behavior that Disney cartoons routinely exclude. But a creeping Disneyism is still apparent throughout much of the movie, and not even the presence of real animals, the beauty of the Bavarian Alps (where the film was shot), and Philippe Rousselot’s wide-screen photography can hold such forces entirely at bay.

The story begins with the cub foraging for food near a beehive on a mountain ledge, with his or her mother doing the same thing nearby. (My uncertainty about the cub’s gender is emblematic of the problems outlined above: the cub, whose real-life name is Douce, is actually female, but Annaud refers to the character in interviews as a he, and I must confess that my own Disney conditioning, combined with the nature of the plot, led me to assume that the cub was male.) Rocks begin to fall from the upper ledges, gradually turning into a small landslide, and the mother is crushed under a boulder. The cub tries to free her by removing some of the smaller rocks, then gives up and chases after a butterfly; eventually he (to capitulate to convention) goes to sleep beside his mother’s dead body, and in the morning descends the mountain alone. Overall, the episode as it’s shown treats the mother’s death matter-of-factly and without sentimentality; but Philippe Sarde’s soupy score refuses to leave it at that, throbbing with conventional human emotion as the cub lies down beside his dead mother.

Further down the mountain, the cub chases a frog into a stream, and the following night has a dream about flying frogs (deftly executed, as are two subsequent dream sequences, by Czech animator Bretislav Pojar). The same night, we get our first glimpse of the two hunters (Chicagoan Jack Wallace and French actor Tcheky Karyo) at their campsite near the foot of the mountain, slicing up bear carcasses. One of them loads a rifle and, in a gesture brimming with symbolic import, aims it silently at the moon. (This gesture is echoed a bit later when the cub sees the moon reflected in a stream and tries to grab it with his paw.)

The next day, the big solitary bear makes his first appearance — a hulking creature whom the older hunter estimates to weigh more than 1,500 pounds. The younger hunter shoots the bear in the left shoulder; the bear runs away before the hunters can get another shot at him, attacking one of the men’s horses in the process. The cub follows this bear from a distance as he limps toward a mud hole and lies down; the bear growls threateningly as the cub gingerly approaches the mud hole, but then relents, letting the cub lick his wound and eventually licking him back. Again due to my own Bambi conditioning, I wrongly assumed when I saw this sequence that the big bear was the cub’s father. It’s certainly true that he becomes his surrogate father, but whether this is plausible or fanciful bear behavior is debatable.

The younger hunter injures his foot, and the older man goes off to get help, leaving his companion somewhat frightened and edgy at their campsite. The next day, the big bear kills an elk that he and the cub eat; they both go to sleep, and the cub, still smeared with the elk’s blood, dreams about bees and his mother’s death. Later the cub watches from a distance as the big bear has sex with another big bear; then the cub goes off to gobble up some magic mushrooms, which bring on a few hallucinations.

A canoe bearing several dogs and their handler (Andre Lacombe) arrives at the campsite, the older hunter returns as well, and they all go off in pursuit of the big bear. After a violent skirmish in which two of the dogs are killed, the cub is captured by the men and tied to a tree at the campsite . . .

Rather than recount the remainder of the plot, I’ll mention only that there’s a remarkable action sequence later on in which a mountain lion chases the cub, and a climactic showdown between the younger hunter and the big bear; both of them wind up showing each other mercy (an event that is less fanciful than it sounds, because it recapitulates an incident that actually happened to the film’s “wild grizzly consultant,” Doug Peacock). The movie concludes with a quote from novelist Curwood: “The greatest thrill is not to kill but to let live.”

It’s an honorable enough conclusion, and, given all the other things that could have been done with the material, an honorable enough movie. What ultimately prevents it from being something more is the fact that Annaud isn’t a better director. Even the film’s virtuosity as a technical feat is frequently undercut by the fact that one is too much aware of it as a stunt to accept it as a story on its own terms; individual moments of animal behavior often work against the desired narrative flow, reminding us of how difficult it must have been to direct the animal “actors” in a work of fiction. Given the splendid settings and Annaud’s professed desire to emulate German romantic landscape painters like Caspar Friedrich and Albert Bierstadt, his compositions are never more than pretty and decorative arrangements that usually depend too heavily on center framing; they never seize the imagination or impress the memory with the force that they aspire to. And Annaud’s handling of the human characters tends to be awkward and tentative: one can sense the overall intention — the desire to show that men can and should aspire to the same nobility as bears — without ever seeing the idea fully developed or carried out.

Eight years ago, Annaud and Brach made another film that tried to present a primeval, unmediated view of raw nature, Quest for Fire — a film about a human tribe struggling to survive 80,000 years ago. (They spoke an unintelligible language created for the film by Anthony Burgess.) Part of the problem with that film was the ideological baggage, sexual as well as racial, that it unwittingly packed along on its quest for purity; as a friend pointed out, you could tell who the hero was easily enough because he was blond and blue-eyed, and one certainly came away from the film feeling that the filmmakers didn’t like women very much. (Brach, incidentally, largely made his reputation by scripting Roman Polanski movies.) The Bear is more sympathetic and more watchable than that earlier effort, but the same sort of strictures wind up applying here, too. Just as composers need to be judged by their musical rests as well as by their notes, filmmakers need to have control over their empty spaces. Too many of the empty spaces in The Bear are filled up by the drivel of Philippe Sarde’s score — or else by weighty ideological baggage that can’t be eliminated by pretending it doesn’t exist.