From Sight and Sound, Winter 1975/1976; also reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. — J.R.

Edinburgh Encounters:

A Consumers/Producers Guide-in-Progress to Four Recent Avant-Garde Films

The role of a work of art is to plunge people into horror. If the artist has a role, it is to confront people — and himself first of all — with this horror, this feeling that one has when one learns about the death of someone one has loved.

— Jacques Rivette interview, circa 1967

For interpersonal communication, [the modernist text] substitutes the idea of collective production; writer and reader are indifferently critics of the text and it is through their collaboration that meanings are collectively produced . . .

The text then becomes the location of thought, rather than the mind. The mind is the factory where thought is at work, rather than the transport system which conveys the finished product. Hence the danger of the myths of clarity and transparency and of the receptive mind; they present thought as prepackaged, available, given, from the point of view of the consumer . . .Within a modernist text, however, all work is work in progress, the circle is never closed. Read more

From Cinematograph, vol. 4, 1991; reprinted in both Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism and Discovering Orson Welles. — J.R.

I want to give the audience a hint of a scene. No more than that. Give them too much and they won’t contribute anything themselves. Give them just a suggestion and you get them working with you. That’s what gives the theatre meaning: when it becomes a social act.

— Orson Welles, quoted in Collier’s, 29 January 1938

Two propositions:

1. One of the most progressive forms of cinema is the film in which fiction and nonfiction merge, trade places, become interchangeable.

2. One of the most reactionary forms of cinema is the film in which fiction and nonfiction merge, trade places, become interchangeable.

How can both of these statements be true — as, in fact, I believe they are? In the final analysis, the issue is an ethical one. In support of 2, there are docudramas that use spurious means to grant bogus authenticity to fiction (MISSISSIPPI BURNING is a good example), and documentaries that employ fictional devices in order to lie more effectively (e.g., Read more

From The Soho News (February 11, 1981), slightly revised. This is the first of my ten Soho News columns with that title, and the only one without a subtitle. — J.R.

Jan. 23; Arriving at the Collective [for Living Cinema] too late to absorb either of Gail Camhi’s 1980 quickies, I’m plunged almost at once into her lovely 22-minute Bellevue Film (1977-78), also silent, which is just what its title and program note say it is: “A look at physical therapy, having profited from it.”

What’s lovely about that?, one might ask, although no one at this crowded screeni9ng seems to be asking it. Russian Formalism associates art with defamiliarization, “making strange”. Gail Camhi seems to be doing just the reverse – showing how ordinary, say, amputees and their stumps and artificial limbs are, making them familiar and banal presences rather than fearfully charged objects. Yet by removing (to some extent) myth and other forms of fantasy from a hospital ward, she may actually be inviting the aesthetic imagination to relocate itself elsewhere in the film – not merely banishing this imagination to purgatory, as some arguments would have it. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 27, 1991). This film is now available on a Criterion Blu-Ray. Although I still have some issues with the film, after reseeing it on this edition, Terry Gilliam’s audio commentary is terrific, and his own enthusiasm for the film is often compelling. — J.R.

THE FISHER KING

Directed by Terry Gilliam

Written by Richard LaGravenese

With Jeff Bridges, Robin Williams, Mercedes Ruehl, Amanda Plummer, Michael Jeter, and Tom Waits.

Terry Gilliam’s elephantine yet breezy The Fisher King is a gripping new-age extravaganza, visually splendid and adroitly paced. But some gross conceptual cheating — presumably the fallout of commercial ambitions — makes the film a little hard to swallow. Gilliam’s fifth feature (he also directed Jabberwocky, Time Bandits, Brazil, and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen) revels in duality — everything comes in twos — so it’s little wonder it indulges in both duplicity and outright doublethink; the film is also littered with internal “rhymes,” both significant and gratuitous. This duality may come partly from the fact that for the first time Gilliam has not written the script himself — it’s by talented newcomer Richard LaGravenese. At any rate the duality echoes Gilliam’s well-advertised desire to make this both an artistic and commercial success — to prove he can turn out a money-maker (after the box-office flop of Baron Munchausen) and yet retain his reputation as an overachiever in the grand style, a director known for his quirky humor and ravishing visual conceits. Read more

From Stop Smiling, issue 36, 2008. — J.R.

It’s easy to argue that most of the greatest filmmakers in the history of movies can’t be reduced to single nationalities, and that an uncommon number of them worked as expatriates. “I’m not at home anywhere,” declares Friedrich Munro (Patrick Bauchau), the expatriate director-hero in Wim Wenders’ underrated The State of Things (1982) — shooting an apocalyptic SF film in a remote corner of Portugal until money suddenly runs out and he has to chase down the producer (Allen Garfield) in Hollywood, who appears to be fleeing from the Mafia. This line is actually a quote from a real-life, very great German expatriate director with a similar name, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. And it might be argued that a condition of homelessness has helped more major filmmakers than it’s hurt, maybe because it’s forced them to reinvent themselves — a process that has also often entailed reinventing their cinema.

Some examples of this tendency may not be immediately obvious. Luis Buñuel is usually regarded as quintessentially Spanish, yet he only made three films that fully qualify as Spanish — a short documentary called Land without Bread (1932) and two features, Viridiana (1961) and Tristana (1970). Read more

Excerpted from a chapter in my book Film: The Front Line 1983. — J.R.

Of all the films discussed at length in this book, Too Soon, Too Late (1981) is conceivably the one that has had the strongest impact on me, although I have seen it only twice. After having seen it the first time, in Spring 1982, I was sufficiently impressed to put the film at the end of my “all-time” top ten list for Sight and Sound’s international critics’ poll later the same year. Consequently, it seems paradoxical yet unavoidable that of all the films dealt with here, Too Soon, Too Late automatically qualifies as the most difficult and elusive to write about. My two previous efforts have yielded only a few inadequate and hastily conceived sentences in the introduction to my Straub-Huillet catalog, and a somewhat more reasoned paragraph in the conversation with Jonas Mekas which opens this book. The notes below cannot pretend to be more than an interim report; further and more extensive analysis will have to await a future date:

(a) First, a few concrete facts about the film. For the first time in a Straub-Huillet film, the texts used are all read off-screen, making separate versions in different languages possible without any recourse to dubbing. Read more

This was written in December 2008, after Dana Linssen, the editor-in-chief of the independent Dutch film monthly de Filmkrant, sent out a request early that month for contributions to what she called a “Slow Criticism” dossier, to appear in their special English-language newspaper at the Rotterdam International Film Festival in late January. I revived it in 2011 as my own contribution to the avalanche of journalism that had been appearing about Pauline Kael, capped by Frank Rich’s lengthy piece in the New York Times; it’s also included in my most recent collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, where it concludes the book’s penultimate section, “Films,” just before its final section, “Criticism”. There isn’t a piece about Kael in the final section, but this broadside helps to explain why.

One aspect of recent journalism about Kael that seems to confirm the provinciality of American film criticism in general is the tacit assumption that “the world of film” in the U.S. is somehow (and automatically) coterminous and equivalent to global film culture — unless the assumption is simply that global film culture is too esoteric and inconsequential a subject to be worthy of discussion in the U.S. But it’s worth stressing that outside the English-speaking world, Kael’s critical status was and is pretty limited. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 27, 1988)….Seeing a more recent Konchalovsky picture, the powerful Holocaust drama Paradise, at Mar del Plata, I was reminded of what a terrific filmmaker he can be, which whetted my appetite to resee his powerful Runaway Train (a recent Twilight Time Blu-Ray that was waiting for me when I returned to Chicago). — J.R.

SHY PEOPLE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Andrei Konchalovsky

Written by Konchalovsky, Gerard Brach, and Marjorie David

With Jill Clayburgh, Barbara Hershey, Martha Plimpton, Merritt Butrick, John Philbin, and Mare Winningham.

I still have a lot of catching up to do with Andrei Konchalovsky. Out of his 11 or so features to date, the last 4 of which were made in the United States, I’ve seen prior to Shy People only 2. The Soviet Asya’s Happiness (1966), a film made with and about Russian peasants, was suppressed for many years because of its supposedly “gloomy” depiction of rural life but surfaced at the San Francisco Film Festival a couple of months ago. The other was Runaway Train (1985), costarring Jon Voight, Eric Roberts, and Rebecca DeMornay and adapted from a script by Akira Kurosawa. But a couple of things are already becoming clear from this limited if striking evidence. Read more

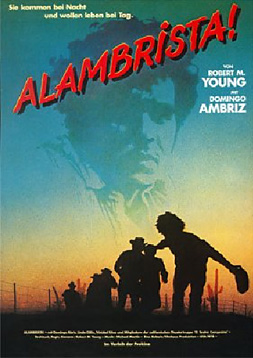

From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 510). –- J.R.

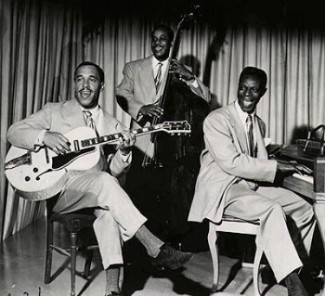

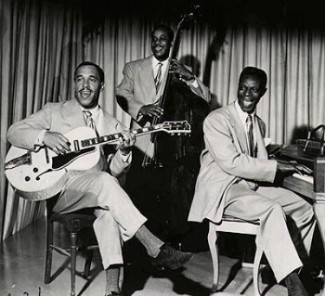

Nat King Cole Trio

U.S.A., 1948

Director: Josh Binney

Dist—TCB. p.c–All-American. p–Glucksman. m/songs–“Oo Kickerooni”, Rooney”, ‘”Now He Tells Me”, “Breezy and the Bass” performed by–Nat “King” Cole (piano, vocals), Johnny Miller (bass), Oscar Moore (guitar). No further credits available. 262ft. 7 mins. (16 mm.).

A musical extract from the Forties black feature Killer Diller — made, like Jivin in Be-bop, exclusively for black audiences — this short illustrates Cole’s remarkable piano playing in a concert, as well as certain aspects of the cooler and more commercial vocal style which he eventually adopted. A graceful, inventive soloist, whose style virtually bridges swing and bebop, with long, perfectly articulated lines which have influenced pianists for three successive decades, he also conveys an unmistakable stage presence — sitting almost perpendicular to the piano while performing difficult runs effortlessly in a manner that is nearly as ‘visual’ as Chico Marx’s. Moore and Miller also takes solos, and the latter is highlighted on “Breezy and the Bass”, a fast virtuoso piece based on the chords of “I Got Rhythm”; “Now He Tells Me” features Cole’s smooth mock-hip singing of the period, exuding a kind of throwaway charm that remains irresistible.

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977 (Vol. Read more

From the July 1980 issue of Omni. Portions of this are derived from a lecture I gave at the Venice film festival the previous year, which is reprinted in my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980). A lot of the terminology used here seems pretty quaint now. — J.R.

Speculating on what movies of the future will be like, it’s hard to get very far without some notion of the changing needs of the audience. A crucial part of this change can be detected in where we see movies. According to present signs, it seems pretty clear that most of the films we’ll see will be either in homes or in shopping malls.

“Once inside a mall, shoppers have few decisions to make,” the magazine Dollars & Sense recently noted. “Corners are kept to a minimum so the customers will flow along from store to store, propelled, as the developers say, by `retail energy’.” It’s a description that fits several recent movie blockbusters — and others we can expect to see in the future.

By contrast, the movie houses that traditionally cropped up near the centers of towns — public gathering places, not unlike the municipal squares they were often adjacent to — are quickly becoming nostalgic emblems of another era. Read more

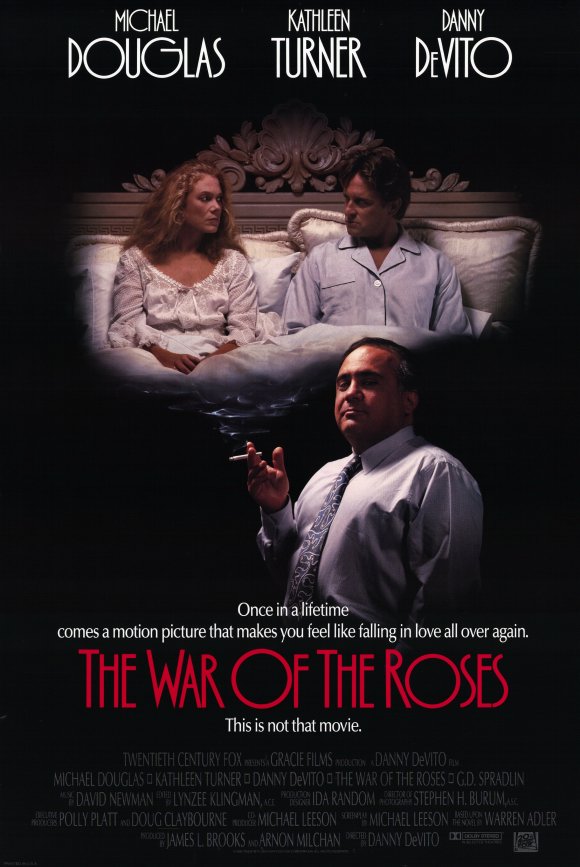

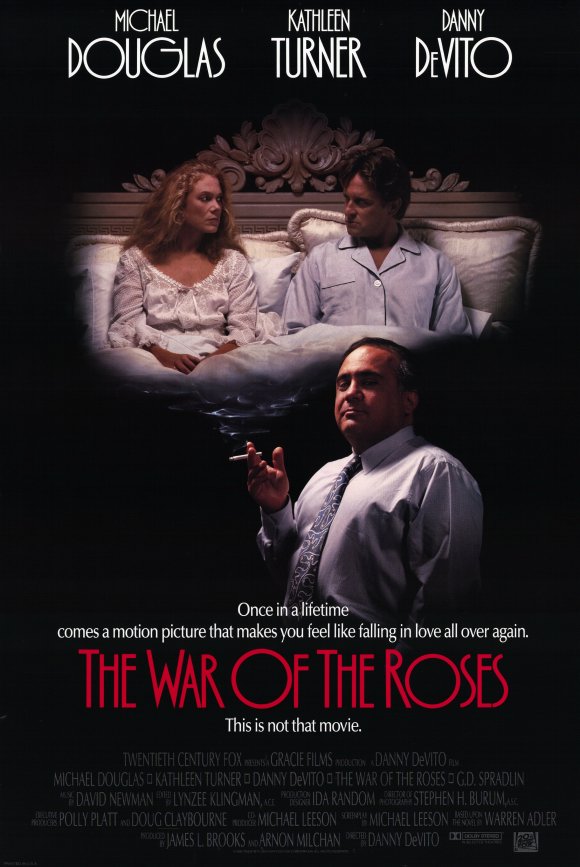

From the Chicago Reader (December 15, 1989). — J.R.

THE WAR OF THE ROSES

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Danny DeVito

Written by Michael Leeson

With Michael Douglas, Kathleen Turner, DeVito, Marianne Sagebrecht, Sean Astin, and Heather Fairfield.

The proper tone for Danny DeVito’s second feature is set by a very short Matt Groening cartoon that precedes every print. A brief cadenza on familial hatred and violence is played out in a therapist’s office, where most of the hatred and violence is directed at the therapist, uniting the family in the process. The War of the Roses opens with another sort of therapist — Danny DeVito as high-priced lawyer Gavin D’Amato — talking to a client in his office. The landscape outside D’Amato’s office looks unusually fake, and DeVito’s delivery seems as self-consciously overarticulated as some of Woody Allen’s recent performances — to mix a metaphor, one can almost see the chalk marks in his verbal punctuation — but both of these oddities actually serve the story he is about to tell about a marriage and its demise.

Unlike the therapist in the Groening cartoon, D’Amato stands mostly outside the story he is telling, and he clearly represents the voice of reason rather than part of the problem. Read more

I am reprinting the entirety of my first and most ambitious book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, New York: Harper & Row, 1980) in its second edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) on this site in eleven consecutive installments. This is the fifth.

Note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

2— On Moonlight Bay as Time Machine

A small Midwestern town in 1916, possibly in June. Behind a succession of pink and green credits that they will never see, acknowledge, or understand—a list of names and functions that fasten themselves to a Warner Brothers release, On Moonlight Bay , dated 1951—a family is seated in the dark parlor of a Booth Tarkington house, watching slides of themselves on a screen.

Taste it if you can: 1916. Tarkington’s Penrod and Sam, a sequel to his very popular Penrod, has either just appeared in hardcover or is about to. Germany has declared war on Portugal, Russia has invaded Persia, 8,636 English and German sailors have perished in a naval battle off Jutland, and Gordon MacRae—whom we hear with Doris Day singing the title tune over the credits, but haven’t yet seen—has just completed his junior year at the University of Indiana, and is deeply shaken by all this strife in Europe. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 14, 1995). — J.R.

Billy Wilder’s soggy and uninspired 1963 adaptation of the hit Broadway musical, minus the songs. Shirley MacLaine stars as a Paris prostitute with a heart of gold who falls for a former policeman (Jack Lemmon) who winds up as her pimp and, in disguise, her only customer. A good example of how a movie can be utterly characteristic of its maker and still fall with a resounding thud; with Lou Jacobi and Herschel Bernardi. (JR)

Department of utter bafflement (February 2015): Thinking I might have missed something (the film was, after all, a smash hit, and was treated by Godard as if it were Wilder’s belated blossoming as a filmmaker, even making the ninth spot in his ten-best list for 1964, between The Nutty Professor and Two Weeks in Another Town), I recently made a return visit to this movie on DVD and found it just as unbearable as before, despite the charm of the Alexander Trauner sets.

Wilder’s major gift, apart from symmetrically pointed plot construction (as in Kiss Me, Stupid and Avanti!), was as a reporter on American bourgeois hypocrisy, and what seems most peculiar in this film is its misreadings of French manners and French bourgeois hypocrisy, which come across as purely American — Parisian pimps out of Damon Runyon (filmed on the same soundstages as Guys and Dolls, at the Goldwyn Studio) and a puritanical cop who seems to hail from the American midwest. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 24, 1993). Oddly enough, the version of this piece that’s available on the Reader‘s web site and (until recently) here is missing the final five paragraphs, which I’ve just restored by copying them from the printed version that I still have in one of my scrapbooks. — J.R.

THE MUSIC OF CHANCE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Philip Haas

Written by Philip and Belinda Haas

With Mandy Patinkin, James Spader, M. Emmet Walsh, Charles Durning, Joel Grey, Samantha Mathis, and Christopher Penn.

In an interview included in his nonfiction collection The Art of Hunger, Paul Auster gives an intriguing account of the major influences on his novels — an account that suggests why these novels aren’t well suited to conventional movie adaptation:

“The greatest influence on my work has been fairy tales, the oral tradition of story-telling. The Brothers Grimm, the Thousand and One Nights — the kinds of stories you read out loud to children. These are bare-bone narratives, narratives largely devoid of details, yet enormous amounts of information are communicated in a very short space, with very few words. What fairy tales prove, I think, is that it’s the reader — or the listener — who actually tells the story to himself. Read more

From The Soho News (January 14, 1981). — J.R.

“When I came to New York in September,” English avant-garde filmmaker and film theorist Peter Gidal tells me, “I noticed that almost every film review that I read used food metaphors and digestion metaphors to talk about art and cinema. Because consumption, digestion and predigestion is the dominant mode in this country. It’s just one signifier of the attempt to break with materialism and process, and to anthropomorphize everything.”

An “English” label should be assigned to Gidal only after some qualification. Born in 1946, he grew up in Mount Vernon, N. Y., and Switzerland and attended Brandeis University before settling in London in the late 60s. Although his accent sounds more redolent of Manhattan than of London, he has spent only two of the past 21 years in the U.S.

Regarding his opposition to food metaphors (as well as narrative), he recalls a drinking cup that he used as a kid for drinking milk. “It had a house on the outside, and on the inside, as you gradually drank, you could see the words, ‘The End.'”

“Which ties up with the idea of closure,” I suggest pedantically, referring to a discussion we’ve been having about Action at a Distance, his latest film. Read more