From American Film (September 1979). –- J.R.

Academic film conferences in the United States seem to be growing more plentiful every year. But there’s only one that can properly be called a theory conference, where theorists congregate, report on works in progress, and generally talk shop. It takes place in Milwaukee, at the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Twentieth Century Studies, usually when there’s still snow on the ground. A few avant-garde filmmakers also traditionally turn up to show their latest wares and join in the discussions.

For academics, the conference functions as a combined brainstorming session, trade fair, and social gathering. For an interested outside observer, it can offer still another way of keeping up — by serving as a kind of barometer of intellectual currents in both films and film studies.

Last year the topic was “The Cinematic’ Apparatus: Technology as Historical and Ideological Form,” and the main attraction was papers by and discussions with many of the reputed superstars of film theory, ranging from Jean-Louis Comolli and Christian Metz [see below] to Stephen Heath and Laura Mulvey. This year the title was “Cinema and Language,” and although there was a lot of both to be squeezed into four days, it was the movies shown that left the strongest impression. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 13, 1992). This film can now be accessed online. — J.R.

THE FAMINE WITHIN

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Katherine Gilday.

Some theorists believe it is the larger North American society that needs healing, that women’s bodies today are the symbolic area in which a larger drama of cultural values is played out. — narrator, The Famine Within

Siskel and Ebert, among others, have been arguing that the documentary nominating committee of the Academy Awards needs a major revamping. Their beef is that the most popular and widely discussed documentaries of the past few years — like The Thin Blue Line, Paris Is Burning, Roger & Me, and Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse — never get nominated. Implicit in this argument is the notion that the most popular movies are usually the best, a notion that the awarding of most of the remainder of the Oscars is predicated upon. To accept any serious challenge to this sacred premise would be to undermine our faith in distributors, exhibitors, critics, publicists — the film industry itself. Perish the thought: if we lost our faith in all of the above, we might actually have to start thinking for ourselves. Read more

Written in August 2016 for my November 2016 “En movimiento” column in Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

Do we value actors for their visible and audible skills, or for their capacity to make us forget that they’re actors? Over the past month, both at the Melbourne International Film Festival and back in Chicago, at cinemas or watching home videos, I’ve been asking myself this question in relation to such new films as Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, Albert Serra’s La Mort de Louis XIV, Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann, Paul Verhoeven’s Elle, David Mackenzie’s Hell or High Water, and Stephen Frears’ Florence Foster Jenkins, and such older films as Anthony Mann’s Winchester ’73, Tony Richardson’s A Taste of Honey, and Jerry Lewis’s Smorgasbord. And, needless to say, my answers to this question differ enormously, mainly according to how familiar I am with the actors involved — which doesn’t necessarily mean how many times I’ve seen them before. For instance, prior to Paterson, I’d already seen Adam Driver in J. Edgar, Frances Ha, Lincoln, Inside Llewyn Davis, and Midnight Special, but I only know this now because I just looked up his credits. Read more

Jean Grémillon remains one of the major French filmmakers whose films are most egregiously unavailable on DVD, especially when it comes to versions with English subtitles — although I’m delighted to report that Criterion’s Eclipse brought out three of his greatest ones, all made during the Occupation, including the two that are discussed here and Remorques. This article appeared in the October 25, 2002 issue of the Chicago Reader. –— J.R.

Lumière d’été **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Grémillon

Written by Jacques Prévert and Pierre Laroche

With Madeleine Renaud, Pierre Brasseur, Madeleine Robinson, Paul Bernard, Georges Marchal, and Marcel Lévesque.

Le ciel est à vous **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Grémillon

Written by Albert Valentin and Charles Spaak

With Madeleine Renaud, Charles Vanel, Jean Debucourt, Léonce Corne, Albert Rémy, and Robert le Fort.

A friend and colleague, critic and teacher Nicole Brenez, says that the best film criticism consists of films critiquing one another. This may sound a mite abstract, but two very different masterpieces by the great, neglected Jean Grémillon, Lumière d’été and Le ciel est à vous, seem to offer a concrete example of this, as a critique of Jean-Luc Godard’s In Praise of Love, which I wrote about last week. Read more

Chapter Two of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). The cover below is that of the U.K. edition published by the Wallflower Press. — J.R.

How often are aesthetic agendas determined by business agendas? This question is not raised often enough.Terminology plays an important role here. For example, once upon a time, previews of new releases were called “sneak previews” because the titles of these pictures weren’t announced in advance. Most industry people continue to use the term, despite the fact that the titles are announced and even advertised, so that the original meaning gets obfuscated: the only thing “sneaky” is the fact that they’re called “sneak previews.”This is a relatively trivial example of how terminology alienates us from what goes on in the world of movies. A more significant example is how we use an extremely loaded term like “independent.” An independent filmmaker traditionally meant a filmmaker who worked independently, free from the pressures of the major studios. If you believe what the media say about independent films, then the mecca for independent filmmaking would be the Sundance Film Festival, an event where independent films and filmmakers congregate annually. Read more

From the April 2015 Sight and Sound. Happily, both versions of both Macbeth and Othello are now available in the U.S. — J.R.

Who ever said Orson Welles’ filmography has to be neat? But one rudimentary way of bringing some order would be to distinguish between nine films he completed to his satisfaction (Citizen Kane, Macbeth, Othello, The Fountain of Youth, The Trial, Chimes at Midnight, The Immortal Story, F for Fake, and Filming Othello) and nine others he didn’t complete and/or lost control of (The Magnificent Ambersons, It’s All True, The Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin, Touch of Evil, Don Quixote, The Deep, The Other Side of the Wind). Yet even this isn’t as neat as it sounds, because he completed two separate versions of both Macbeth (1948 and 1950 — the second at the studio’s request — to eliminate the Scottish accents and shorten the running time by two reels; both are available today in France) and Othello (1952 and 1953; neither, alas, is commercially available anywhere — only an alteration of the second version, edited for the U.S. Read more

Chapter Seven of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). The cover below is that of the U.K. edition published by the Wallflower Press. Because of the length of this chapter, I’m posting it in two parts. — J.R.

TRANSATLANTIC REALITY AVOIDANCE: A REPORT FROM THE FRONT (MAY 1999)

“ ‘I think, therefore I am,’ ” reads the opening epigraph of The Thirteenth Floor, the fourth virtual‐reality thriller I saw in Chicago in as many weeks in the spring of 1999, followed by the quotation’s source, “Descartes (1596–1650).” It’s an especially pompous beginning for a movie whose characters scarcely think, much less exist, but not an unexpected one given the metaphysical claims and pronouncements that usually inform these thrillers.

If any thought at all can be deemed the source of these pictures cropping up one after the other — with the exception of David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, a film with a lot more than generic commercial kicks on its mind — this might be an especially low estimation of what an audience is looking for at the movies. The assumed desire might be expressed in infantile and emotional terms: “I don’t like the world, take it away.” Read more

Chapter Seven of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). The cover below is that of the U.K. edition published by the Wallflower Press. Because of the length of this chapter, I’ll be posting it in two parts. — J.R.

Is it possible that because of the rise of the new media, which have given us the ability to manufacture what we call virtual reality, we are now able, without quite knowing what we are doing, to create a secondary world that we are liable to mistake for the primary world given to our senses at birth? If so, the prime need it serves is probably not political at all but the one Freud identified as the chief motive for dreaming: wish fulfill-‐ ment—a need catered to both by our luxuriously proliferating sources of entertainment and the means of their support, namely, advertisement of consumer products. In our variant of self-‐deception, pleasure plays the role that terror plays under totalitarianism.

— Jonathan Schell, “Land of Dreams,” The Nation, January 11/18, 1999

This chapter and the next explore complementary and mutually alienating attitudes: the desire to keep out foreign influences in order to preserve American “purity,” and the fact that what we consider American “purity” is often composed of foreign influences.

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1992). — J.R.

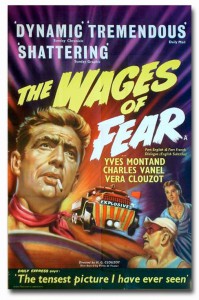

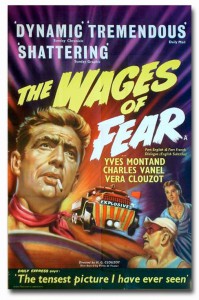

In Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 suspense classic, four out-of-work Europeans (Yves Montand, Charles Vanel, Folco Lulli, Peter Van Eyck), trapped in a squalid South American village that’s exploited by a U.S. oil company, agree to drive two truckloads of nitroglycerine over 300 miles of primitive roads in exchange for $2,000 eachif they survive. When this existentialist shocker opened in the U.S., 43 minutes had been hacked away, but the gripping adventure elements left intact were still enough to turn the film into a hit. (This restored and at least semicomplete version of the film, 148 minutes long, was released in the early 90s.) A significant influence on Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, this grueling pile driver of a movie will keep you on the edge of your seat, though it reeks of French 50s attitude, which includes misogyny, snobbishness, and borderline racism. It’s also clearly a love story between two men (Montand and Vanel). In French with subtitles. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Summer 2015 Artforum.(This version is slightly different.) — J.R.

Doctor (off): Has this happened to you before?

Ventura: It will happen again, yes it will.

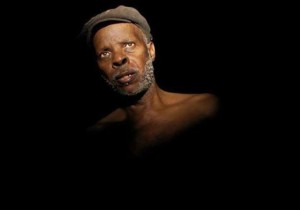

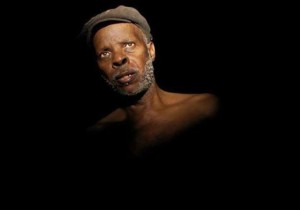

Trying to rationalize Pedro Costa’s Horse Money in terms of a synopsis is ultimately a fool’s game, but connecting it to recent Portuguese history is a necessity. The April 25, 1974 military coup known today as the Carnation Revolution, led by the leftwing MFA and ending the Estado Novo dictatorship that lasted almost half a century, took place when Costa was in his early teens. Ventura, Costa’s slightly older principal protagonist in practically all of his other recent films — a Cape Verdean immigrant and construction worker, always playing himself and scripting his own dialogue — was around in Lisbon too. But as Costa told Mark Peranson in an interview in Cinema Scope, Ventura’s experience of the same events was radically different:

I was very lucky to have been a young man in a revolution, really lucky….And I was discovering a lot of things, music and politics and film and girls, everything at the same time, and I was happy and anarchist and shouting in the streets and occupying factories and things like that — I was 13 so I was a bit blind. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 14, 2004). This is probably my favorite Maddin feature to date. — J.R.

Mannerist film antiquarian Guy Maddin takes a bold step forward with this 2003 feature, a comic/melodramatic musical enhanced by his flair for expressionist studio shooting (in grainy black and white, with selected scenes in two-strip Technicolor). The project originated as a script by novelist Kazuo Ishiguro; revising extensively, Maddin and George Toles, his usual collaborator, turn it into an allegory about Canada’s colonial relationship with the U.S. In the depths of the Depression, a Winnipeg beer baroness (Isabella Rossellini) launches an international contest to come up with the saddest music in the world. Competing for the U.S. is her former lover (Mark McKinney), a brassy Broadway producer; for Serbia the producer’s older brother (Ross McMillan), who grieves for his dead son and vanished amnesiac wife (Maria de Madeiros); and for Canada both men’s father (David Fox), a surgeon who’s drunkenly amputated Rossellini’s legs. Not to be missed. 99 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 16, 2004). — J.R.

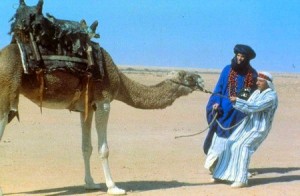

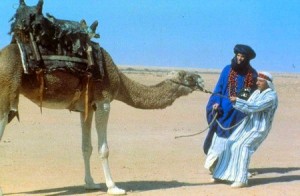

Treated as a debacle upon release, partially as payback for producer-star Warren Beatty’s high-handed treatment of the press, this Elaine May comedy was the most underappreciated commercial movie of 1987. It may not be quite as good as May’s previous features, but it’s still a very funny work by one of this country’s greatest comic talents. Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, both cast against type, play inept songwriters who score a club date in North Africa and accidentally get caught up in various international intrigues. Misleadingly pegged as an imitation Road to Morocco, the film is better read as a light comic variation on May’s masterpiece Mikey and Nicky as well as a send-up of American idiocy in the Third World. Among the highlights: Charles Grodin’s impersonation of a CIA operative, a blind camel, Isabelle Adjani, Jack Weston, Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography, and a delightful series of deliberately awful songs, most of them by Paul Williams. 107 min. A 35-millimeter print will be shown. Univ. of Chicago Doc Films.

Read more

Read more

From the April 23, 2004 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

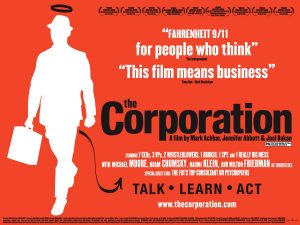

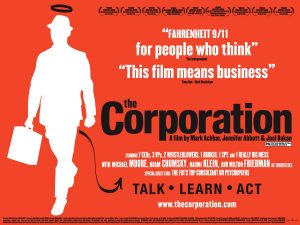

Absorbing and instructive, this 2003 Canadian documentary tackles no less a subject than the geopolitical impact of the corporation, forcing us to reexamine an institution that may regulate our lives more than any other. Directors Mark Achbar (Manufacturing Consent) and Jennifer Abbott and writer Joel Bakan cogently summarize the history of the chartered corporation, showing how it accumulated the legal privileges of a person even as it shed the responsibilities. This conceit allows the filmmakers to catalog all manner of corporate malfeasance as they argue, wittily and persuasively, that corporations are clinically psychotic. The talking heads include not only political commentators like Noam Chomsky, Milton Friedman, Naomi Klein, Michael Moore, and Howard Zinn, but CEOs such as Ray Anderson, Sam Gibara, Robert Keyes, Jonathon Ressler, and Clay Timon, whose insights vary enormously. This runs 145 minutes, but it’s so packed with ideas I wasn’t bored for a second. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 2004). — J.R.

A newly appointed homicide detective in San Francisco (Ashley Judd) tracks a serial killer whose victims are all men she has slept with. Director Philip Kaufman, who usually writes his own scripts, works with a cliche-ridden screenplay by Sarah Thorp, and his personal touches mainly seem to consist of selecting fashionable North Beach bars as locations. His usual flair for erotic detail largely deserts him here, and this thriller seems most interested in lingering over battered and bloodied male faces. Samuel L. Jackson and Andy Garcia costar. R, 97 min.

Read more

Read more

From the May 14, 2004 Chicago Reader. P.S. I once went to hear Cecil Taylor at a San Francisco club in the 1980s with Nathaniel Mackey (as well as Trinh T. Minh-ha and the late Bell Hooks).- J. R.

Any musician of Cecil Taylor’s caliber deserves sustained attention, but the jazz great doesn’t get it in this rambling assortment of alternating sound and music bites. Taylor is a nonstop pontificator of varying interest as well as a brilliant and virtuosic avant-garde pianist, but director Christopher Felver treats his music and his remarks as equally relevant, cutting between them — or away to still photographs — as if determined not to focus too long on any one thing. On piano Taylor employs an idiosyncratic technique, sometimes using his elbows as well as his fingers, and I’d hoped the camera angles would reveal this; apart from a brief shot behind the final credits, however, Felver shows almost everything except the keyboard. At least the other talking heads have things to say, including Elvin Jones, Amiri Baraka, Nathaniel Mackey, and Al Young. 71 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more